“What is Brazil? Half a dream and half a nightmare” – Jonathan Pryce

Apparently it’s 31 years since Terry Gilliam‘s glorious 1985 dystopian reimagining of Orwell‘s classic Nineteen Eighty-Four (which Gilliam claims never to have read) hit our screens, but Brazil is still as fresh, funny, satirical and nightmarish as ever it was originally, and all the more so for being designed in retro-futuristic style. But what does it have to do with Brazil, I hear you ask? Wikipedia:

The film is named after the recurrent theme song, Ary Barroso‘s “Aquarela do Brasil“, as performed by Geoff Muldaur.

Rather less erudite than Gilliam’s intended title of 1984½ (reference also to Fellini‘s 8½), but a clever leitmotif nonetheless.

It is perhaps a reminder that Gilliam films are typically loved by actors and audiences (Rotten Tomatoes 98%) but not by studios or many critics (Roger Ebert 2/4 stars.) The film has effortlessly achieved cult status and is the subject of many a blog (see here, here and here for three fine examples of bloggers raving about the movie.) That Jonathan Pryce described it as the highlight of his career is telling.

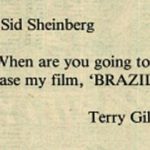

Indeed, some describe this as the best movie of all time, praise indeed considering the battles Gilliam had and has always had to prevent his movies being manipulated by the dead hand studios and distributors, notably to prevent happy endings being artificially tacked on as audience pleasers – which makes Gilliam something of an Orson Welles for the modern era.

There are diversions along the way in this beautifully nuanced and frequently hilarious film; among many other topics it lampoons petty bureaucracy, totalitarian authority (with the same ironic line in posters that Orwell applied to Ministry names), cosmetic surgery, financial service salesmen, dysfunctional machinery and heating systems, but it is the overarching vision and visuals that make the film live long in the memory.

As with pretty much all Gilliam features, just as with his contributions to Monty Python, Brazil contains some of the most visually stunning designs and conceits ever delivered to the big screen. The sections copied from Wikipedia on the director’s virtuoso production art design demonstrates much about his attention to detail.

Critics typically argue his movies have been hit and miss, regularly fail to achieve their targets, but then the greatest creative visionaries have often fallen foul of those lacking the insight – and there are many more egotistical movies around. Unlike many I could name, Gilliam’s narrative is at all times comprehensible, the plot whimsical but disturbing, and the only real flaw that the imposed chase and happy ending seems bizarre in view of what went before.

Gilliam’s version of Winston Smith is Sam Lowry (Pryce), a junior clerk with expertise in the bizarre computer system used in this parallel universe and a mother who moves in high social circles and who is ambitious for him, is woken from a dream in which he is flying with angel-like wings to see his veiled lover to find it is 11am and the automated devices in his flat are playing havoc. Oh, and by pure chance he meets his true love, who drives an articulated lorry, though she initially seems less than convinced.

As the movie progresses, things inevitably get sillier, but without losing the visual inventiveness, nor the menacing edge. That a romantic farce with political satire stays the course is credit not only to the director but also a magnificent cast. Gilliam’s ability to attract an A-list cast comprising some of the finest British and American talent in leading and cameo roles says much about his style and ability.

Pryce apart (he is always excellent), I love the wonderful Peter Vaughan’s very English form of wheelchair-bound Deputy Minister, Michael Palin‘s polite and civilised torturer, Bob de Niro‘s rebel engineer, Ian Holm‘s gratefully paranoid boss Kurtzmann and Ian Richardson‘s shark-like ever-moving barking orders boss at Information Retrieval, Warrenn. Gilliam was reportedly unhappy with Kim Greist‘s fetching Jill Layton, but I imagine he was thrilled with Katharine Helmond‘s Ida. And so it goes on: I’ve not even mentioned Jim Broadbent, Bob Hoskins, Bryan Pringle or Gorden Kay!

Everywhere you look there are marvels, starting with the swatted fly dropping from the ceiling on to a chattering teleprinter and changing a T to B, thus framing Mr Buttle and causing his flat to be invaded from above, he to be arrested and his widow (for Mr Buttle will not return) to be charged for the costs of his arrest. Iconic images abound and collide: the vast chimney where Palin’s Jack, resplendent in a baby mask, is set to torture Sam; de Niro’s Tuttle being coated in paper before apparently dissolving into thin air; Mrs Terrain’s nightmarish funeral, dream battles with an evasive be-masked Japanese Samurai warrior – though everyone will have their own personal favourite image.

The tone of the film is not as biting as an Orwell, not possessed of the gravitas to be a classic, but as with the best there is sufficient complexity that you can dip down into Brazil and find new things on each subsequent viewing.

I look forward to the director’s cuts of each to see how the director envisaged his films, though as is the ending can best be described as bittersweet, with Sam escaping permanently into his dreamworld and thus evading the terror all around.

Art design

Michael Atkinson of The Village Voice wrote, “Gilliam understood that all futuristic films end up quaintly evoking the naïve past in which they were made, and turned the principle into a coherent comic aesthetic.” In the second version of the script, Gilliam and Alverson described the film’s setting like this: “It is neither future nor past, and yet a bit of each. It is neither East nor West, but could be Belgrade or Scunthorpe on a drizzly day in February. Or Cicero, Illinois, seen through the bottom of a beer bottle.”

The result has been dubbed “retro-futurism” by fellow filmmakers Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro. Generally called “sci-fi noir,” it is “a view of what the 1980s might have looked like as viewed from the perspective of a 1940s filmmaker.” It is an eclectic yet coherent mixture of styles and production designs derived from Fritz Lang‘s films (particularly Metropolis and M) or film noir pictures starring Humphrey Bogart: “On the other hand, Sam’s reality has a ’40s noir feel. Some sequences are shot to recall images of Humphrey Bogart on the hunt and one character (Harvey Lime) may be named as an homage to The Third Man‘s Harry Lime.” A number of reviewers also saw a distinct influence of German Expressionism, as the 1920s seminal, more nightmarish, predecessor to 1940s film noir, in general in how Gilliam made cunning use of lighting and set designs. A brief sequence towards the end, in which resistance fighters flee from government soldiers on the steps of the Ministry, pays homage to the Odessa Steps sequence in Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925).

This eclectic virtuosity and attention to detail in lighting and set design was coupled with Gilliam’s trademark obsession for very wide lenses and tilted camera angles; going unusually wide for an audience used to mainstream Hollywood productions, Gilliam made the film’s wide-angle shots with 14mm (Zeiss), 11mm, and 9.8mm (Kinoptik) lenses, the latter being a recent technological innovation at the time as one of the first lenses of that short a focal length that did not fish-eye. In fact, over the years, the 14mm lens has become informally known as “The Gilliam” among film-makers due to the director’s frequent use of it since Brazil.