“Day after day, week after week, month after month, she waits for him. She knows that a love as perfect as hers, as pure and powerful, could never fail to bring him back, across the ocean. He will return. She is sure he will. One fine day.”

Madame Butterfly is the story of a Japanese-American culture clash, written in Italian and performed here in English. If you imagine West Side Story starting with the wedding of Tony and Maria, that’s where Puccini‘s Butterfly begins. Like WSS it is a tragedy, one in which the endless love and naive loyalty of the heroine is roundly abused by First Lieutenant Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton, the swine, to the point where she hands over their child back to his new wife and kills herself.

That sounds facile, but the story is saturated in aching emotion and sung in heartfelt anguish. That this is a somewhat harsh translation detracts from the beauty of Puccini’s libretto, but the feeling is undeniably present – or is it? My companion told me she expected to weep buckets, though I never felt the urge – and, perhaps unusually for a man, I am wont to shed the odd tear at an emotional story. Hold that thought for a moment.

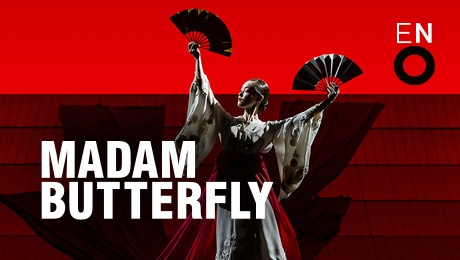

This is a revival of the original 2006 ENO production (see here) directed by the late Anthony Minghella (much in the way that the recently shown Mikado was the umpteenth revival of Jonathan Miller‘s production – clearly aiming to fill seats.) Minghella was best known for gorgeous films like The English Patient, but his operatic work won him widespread praise. This quote is included in the ENO’s web page:

Madam Butterfly is one of opera’s most enduring tales of unrequited love. With its breathtaking mix of cinematic images, traditional Japanese theatre, colourful costumes and stunning sets, Anthony Minghella’s Olivier Award-winning production has been hailed as ‘the most beautiful show of the year’ (Sunday Telegraph)

Other critics are now re-evaluating the revival, with mixed results. Some reviews are decidedly sniffy, hovering around the 3 stars. This might seem harsh, and it certainly contrasts with glowing reviews from audiences new to the production. So what, you may justifiably ask, is the truth?

The curtain goes up to… complete silence. No overture, no nothing but a rising screen to reveal red light, which subsequently cycles through the spectrum of daily skies as the action proceeds. Before any music we enjoy a gloriously elaborate fan dance (fandango?) by Ciccio-San (Miss Butterfly as she then is, 15 and pure), and an elegantly choreographed unwinding of her ribbonlike red sashes (“obi” being the correct name) into a large diagonal cross to the four points of the stage, which obi is at the death used to signify Butterfly’s blood spreading across the stage as she stages her ritual suicide.

The stage consists of black lacquered slope tapers down towards the audience, looking vaguely like a skateboard jump but strategically designed so the audience can see the heads of those who walk behind, silhouetted against the bright skyscape. Their presence announced, they climb the steps and come gradually into view before stepping cautiously down the slope as best the elaborate costumes will allow, mirrored by a second black lacquered platform at an obtuse angle hanging above to reflect the action below. Given the colourful Japanese costumes, this is a ravishing spectacle, matched in turn by props and staging.

The set has been cunningly designed to incorporate traditional Japanese culture, notably the screens which slide across the entire width of the stage; pink cherry blossom recreated in origami on the backs of crew members, and indeed the origami birds flying across the sky on sticks; beautifully mounted paper lanterns that look for all the world as if they are floating; and indeed the traditional Japanese puppetry (“bunraku“), whereby Butterfly’s son is animated by three black-clad and veiled crew, each resembling a poised ninja.

Authentic to a tee, all the better to contrast with the American culture to which the married Butterfly aspires. That said, the puppetry, apparently loved by those not expecting it, did not add great value for me. Maybe puppets are cheaper than employing real life children, but as a theatrical device it seemed to be there largely for effect.

The first scene sets out Pinkerton’s stall. He is a sailor, a dilettante, forever on the move wherever his ship and the winds take him. If he is with you he is with you, but when he goes he never looks back – and believes Japanese culture, with its geishas and easy divorces, supports his view. To Butterfly, her marriage vows are sacred and permanent, an immutable fixture – so each goes into the marriage with completely different views of the future, such that tragedy is inevitable. You can see from the start what will happen, but Butterfly waits, day in day out, for the return of her husband – until he appears with his new American wife.

As ever, Puccini’s score is emotionally irresistible, soothed by the fine orchestral accompaniment under the direction of Sir Richard Armstrong. It is a fragile flower, requiring a delicate and subtle rendition. Some feel soprano Rena Harms to have too robust a voice for the sorrowful Butterfly, though her One Fine Day is worthy of comparison with the Maria Callas benchmark. I disagree – it is a flexible tool and conveys emotion with subtlety. Harms’s only real problem is that she is quite evidently not 15 and therefore is too sophisticated for the innocent Butterfly, though her acting is of sufficiently high standing for the audience to suspend disbelief, as with the puppet son.

Perhaps it demonstrates the quality of performances that David Butt Philip as Pinkerton was booed and hissed as he took his bows, though to me he seemed too flimsy a character to be totally convincing. Pinkerton should be a charmer, but his final redemption (Addio, fiorito sail – “farewell, flowery refuge”) demands complete contrition and torment; he sounded mildly perturbed, as if he had forgotten to pay a tax bill by the deadline.

For me the best characterisations were George von Bergen‘s Sharpless and Stephanie Windsor-Lewis as the maid Suzuki. Von Bergen’s peerless baritone is spot on for the hapless intermediary Sharpless, United States consul at Nagasaki. He is troubled and ultimately disgusted by Pinkerton’s behaviour, but stays loyal to the American citizen, as his job demands. Windsor-Lewis’s mezzo-soprano contrasts with the soprano of Harms and provides soothing company, while voicing her concerns to Sharpless.

I concur with the view that this is unquestionably a spectacular and charming production, one worthy of the ENO and deserving to be seen, though whether any aspects should be re-evaluated over time audience and critics remain divided. So it didn’t involve me sufficiently to feel emotional, but it still gets a solid 4 stars out of 5.