This reminds me of being with my kids at San Francisco in 2011. We tried to get on a tour of “the rock” – as Alcatraz prison was less-than-affectionately known by its former residents – but found only one boat actually stopped there, and that had to be booked some while in advance. We could see Alcatraz from the shore, sitting in the middle of the harbour, but we were denied a chance to try the cells out for size. So near to the city, yet so far – the temptation to escape across the forbidding stretch of water was clear, but doomed to failure.

That said, Adam has an X-box game which allows him to attempt escape from Alcatraz, which for some reason has become infested with zombies (this might explain a lot about the current state of America, but that’s another debate.) Zombies or not, it seems using the game to escape was a damn sight easier than the real thing.

There are plenty of movies about escaping from Alcatraz (see the list here), most famously the Birman of Alcatraz, also based on a true story but heavily fictionalised. But while Alcatraz might be iconic as far as US prisons go, it is not the only host of prison stories. I re-watched Escape From Alcatraz a couple of weeks after re-watching The Shawshank Redemption with my son.

The comparison is undeniable, all the more so since one is “based on” historical fact and the other based on a Stephen King short story. Both involve a variety of interesting characters incarcerated for different terms, and the imperative of escaping – finally achieved by remarkably similar ends; but one ends suddenly while the other plots a very satisfying resolution. Guess which is which?

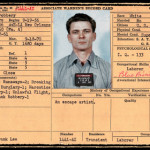

In this case the main protagonist is serial escaper, Frank Morris, played by eternal tough guy and sometime mayor of Carmel-by-the-sea, Clint Eastwood. I have no way of knowing how closely the inmates portrayed bear any relation to their real-life counterparts, but Eastwood’s Morris does not take any prisoners, so to speak. He does not take any crap from the friendly neighbourhood rapist, known as the Wolf, suffers two murderous attacks and a period in “the hole” for his pains. Having said that, most inmates seem decent sorts, if eccentric – not unlike Shawshank, come to that. Of the fictional villains of Alcatraz, Wikipedia says this:

The character Charlie Butts is fictional. A fourth inmate, Allen West, did participate in the real escape but was left behind when he couldn’t remove his ventilator grille on the night of the escape. He aided the FBI’s official investigation of the escape.

Wardens – now there’s a thing. By comparison to Bob Gunton‘s magnificently evil bible-bashing warden Norton in Shawshank, Patrick McGoohan‘s unnamed Alcatraz warden is sparing with his words but predictably ruthless. He seems to share a number of qualities with no 6 in The Prisoner, which was perhaps a nicely ironic reason for casting McGoohan in the role. Anyway, Wikipedia says this about the warden scenario:

The warden is a nameless, fictional character. The film is set between the arrival of Morris at Alcatraz in January 1960 and his escape in June 1962. Shortly after arriving Morris meets the warden, who remains in office over the course of the entire movie. In reality, however, warden Madigan had been replaced by Blackwell in 1961. The warden character mentions his predecessors Johnston (1934–48) and (incorrectly) Blackwell (1961–63).

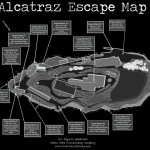

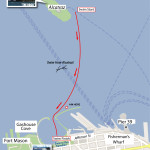

Back to the story: imagine Morris and his buddies are now well settled in but being watched closely by the finest guards, who nonetheless think nobody can possibly escape the Rock. Even in the unlikely event that they find a way out of the prison, it’s 1.5 miles to shore, no boats, a fearsome current and ice cold water.

Morris spots a way to dig a hole from his cell and to disguise it from the frequent inspections. At night he and his buddies make the holes in their respective cells bigger, make imitation grids to cover the holes and imitation heads to give the impression that they are sleeping during guard rounds. Eventually they break through and at great length find ways through the prison architecture until a way out of the building is discovered (in the interests of brevity I’ll skip the detail on that stage), much as Andy Dufresne does in Shawshank.

Are you getting the picture here? Sounds rather like Stephen King borrowed heavily from the escape of Morris and the Anglin brothers, though there the similarity stops. Where Dufresne crawls through the prison sewer to achieve freedom and find a neat way to get revenge on the loathsome Norton, Morris and the Anglins vanished. Yes, the movie stops there, without even a hint of speculation over what might have happened to them. Interesting then that Wikipedia adds to its narrative as follows:

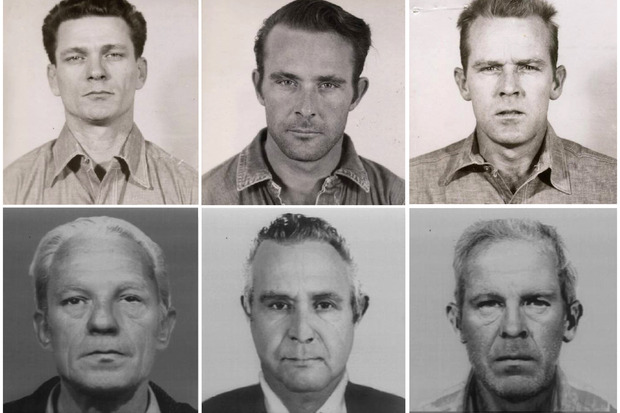

While it is not known whether the three escapees survived, sightings of them over the years provides circumstantial evidence that they may have.

So while the warden is convinced they died a horrible death, and goes to face an uncomfortable audience with his bosses, nobody truly knows what happened to them, and the film sits on the fence, which from a dramatic perspective is a total and unanswerable cliffhanger.

Ah, but there is one reality mentioned in the closing screen narrative: Alcatraz was closed shortly after the true events on which the film was based. Why? Wikipedia explains:

Because the penitentiary cost much more to operate than other prisons (nearly $10 per prisoner per day, as opposed to $3 per prisoner per day at Atlanta), and half a century of salt water saturation had severely eroded the buildings, then Attorney GeneralRobert F. Kennedy ordered the penitentiary closed on March 21, 1963. In addition, citizens were increasingly protesting the environmental effects of sewage released into San Francisco Bay from the approximately 250 inmates and 60 Bureau of Prisons families on the island. That year, the United States Penitentiary in Marion, Illinois, on land, opened as the replacement facility for Alcatraz.

So in short, Escape from Alcatraz is ultimately less satisfying than Shawshank, in spite of or maybe because of its insistence of sticking to at least some of the truth. But if fictionalising characters and situations was fine, maybe identifying a few scenarios at the end would not have hurt. After all, computer science has even provided us with pictures of how the trio might have appeared in old age (see below) and evidence of what could have happened to them (see here.) I’ll let you make up your own mind.