“We’re an army of ghosts”

The Railway Man is based on a true story, but is not the first movie to be based on the same source material. As with all such adaptations, the action is compressed and liberties were taken for dramatic effect, though it has been given for the accuracy of its historical interpretation a generous 3 stars out of 5 by an expert on such matters, Dr Philip Towle from the University of Cambridge. The question for this review is whether it succeeds in its own right as a movie.

No doubt that some of the story has been hyped for suspense, making Eric Lomax (who died at the age of 93 not long ago) appear far more raw, fragile and emotional than in real life, but in essence this is indeed what happened: railway enthusiast boy meets girl on train (girl in question being 17 years his junior), woos and marries her (having first divorced his first wife, not mentioned in the film), shaves his tash and loses the dowdy specs.

But alas, this is not entirely a happy-ever-after tale, at least not at that point. Lomax then becomes heavily withdrawn, haunted by memories of being a Japanese PoW and of the torture that destroyed and killed many men in the construction of the Thai-Burmese railway. In particular, his relationship with the one man responsible for most of his torment, the guard known as Takashi Nagase, which starts as a lust for revenge but then matures into a need for understanding, of which more later.

You can’t argue with the raw ingredients here. Jonathan Teplinsky has assembled a good cast and provided them with both a sensitive script (courtesy of Frank Cottrell Boyce and Andy Paterson), and demonstrated the wit to observe from a distance without forcing the pace.

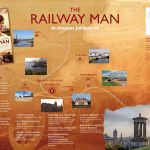

Colin Firth, replete with the gravitas of an Oscar winner who has shaken off the light-hearted villain of earlier movies in order to inhabit the skin of weightier characters, looks completely at home as the older Lomax, while Jeremy Irvine as his younger self keeps the side up and looks unnervingly like the older Firth. Both look acceptably like the real Lomax (see pic above) and portray the diffident but charming-in-an-old-fashioned-sort-of-way personality with some degree of accuracy.

As Lomax’s prime interlocutor, Patti (Nicole Kidman), the woman won over by his charm and determined to make sure she gets her man back from the hell-hole to which he has descended, helps unfold the narrative on our behalf. Kidman plays Patti with a certain old-world charm herself, and both Firth and Kidman employ self-restraint to good effect, this being the sort of drama where the goal is to hint at the 90% of proverbial iceberg without actually overtaking the script in its portrayal. That comes from Lomax’s flashbacks and eventually his visit back to the land where he was so cruelly held prisoner.

The point of the story is confronting the source of trauma that caused interminable post-traumatic stress, requires bravery but forces some closure. One of Lomax’s erstwhile colleagues from the PoW camp, Finley (Stellan Skarsgård) tries to confront his own demons from that time and the bravery shown by Lomax in allowing himself to be beaten to protect the others, but is ultimately defeated by them.

For Lomax it is the memory of torture by Nagase, a Kempeitai officer masquerading as a translator, that numbs his brain – with good reason too, for the torture in question is waterboarding, simulated drowning. The same torture the CIA used on those enemies they deemed terrorism suspects but publicly denied torturing. This is from Wikipedia:

Dr. Allen Keller, the director of the Bellevue Hospital/New York University Program for Survivors of Torture, has treated “a number of people” who had been subjected to forms of near-asphyxiation, including waterboarding. In an interview for The New Yorker, he argued that “it was indeed torture. ‘Some victims were still traumatized years later’, he said. One patient couldn’t take showers, and panicked when it rained. ‘The fear of being killed is a terrifying experience’, he said”. Keller also gave a full description in 2007 in testimony before the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence on the practice:

The CIA’s Office of Medical Services noted in a 2003 memo that “for reasons of physical fatigue or psychological resignation, the subject may simply give up, allowing excessive filling of the airways and loss of consciousness”.

In an open letter in 2007 to U.S. Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, Human Rights Watch asserted that waterboarding can cause the sort of “severe pain” prohibited by 18 USC 2340 (the implementation in the United States of the United Nations Convention Against Torture), that the psychological effects can last long after waterboarding ends (another of the criteria under 18 USC 2340), and that uninterrupted waterboarding can ultimately cause death.

Alas, the Japanese did not stick to the UN Convention on Torture; granted it did not exist in WWII, but even if it had evidence suggests the cruelty and barbarity applied to PoWs would have known no limits, quite apart from the slave labour from which very many did not return. Of course it’s far more than that: the subjugation and enforcement of will against a person unable to defend themselves is psychological torture – the physical torture leaves scars to ensure there is always something to remind the victim.

In this case 20-odd years later the passions it evokes could lead you to understand why Lomax would have thoughts of revenge, when finally he faces his captor once again (even if this did not happen in real life.) But the poignant psychology really comes when Lomax offers the man he had considered the embodiment of death the quality of his mercy – forgiveness and ultimately friendship – and in the process saving his relationship with Patti. A quote from Firth and recorded in Wikipedia:

“I think what is not often addressed is the effect over time. We do sometimes see stories about what it’s like coming home from war, we very rarely see stories about what it’s like decades later. This is not just a portrait of suffering. It’s about relationships … how that damage interacts with intimate relationships, with love.”

In the final analysis, a film that remains stoically straight faced and unemotional against the tide of cruelty perpetrated against Lomax in Thailand, and, inadvertently, by Lomax against his gentle and loving wife, finally hits the tear buttons in the final reconciliation. That it is so nobly restrained for so long is credit to both director and stars for eschewing melodrama and over-emoting. It is much the better film for choosing this path.