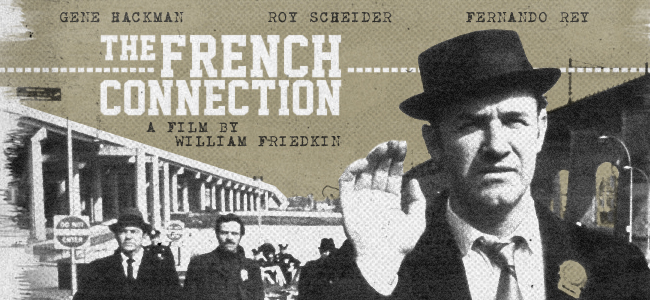

The French Connection is the archetypal gritty cop movie, not to mention cops-chase-drug-dealing-villains movie – the 1971 epic which spawned hundreds if not thousands of inferior me-too’s.

The sequel (French Connection II) deals more directly with the effects of the drugs, but the first sees two of the NYPD’s finest, Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle and Buddy “Cloudy” Russo (respectively Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider) doing the stakeouts and tracking down the criminal mastermind, Alain Charnier (Fernando Rey) who is planning a massive shipment of pure heroin that would otherwise filter down to the streets and give the police an impossible job to keep track of the small-time pushers and dealers, their bread and butter. We see them going about their business, dealing with an unsympathetic boss and nearly coming to blows with the Feds who accompany them on the chase. It’s not a happy life: Rey and accomplice eat gourmet food in a fine restaurant while Doyle and Russo freeze their nuts off in the cold while eating slices of pizza and drinking coffee not fit for prisoners.

Essentially this is a movie with a simple plot, though the ending is deliberately a touch enigmatic. TFC won Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director (William Friedkin), Best Actor (Hackman), editing and screenplay by virtue of being gripping from start to finish. It also stays long in the memory by virtue of using actual locations around NYC, many of them showing the seamier side of this wonderful city, better than almost any similar movie, and some of the most stunning set pieces you will ever come across.

Of course, if you are an action freak then the car chase may be your primary fascination, so here is the full detail, courtesy of Wikipedia:

The film is often cited as containing one of the greatest car chase sequences in movie history. The chase involves Popeye commandeering a civilian’s car (a 1971 Pontiac LeMans) and then frantically chasing an elevated train, on which a hitman is trying to escape. The scene was filmed in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn roughly running under the BMT West End Line (currently; the D train, then the B train) which runs on an elevated track above Stillwell Avenue, 86th Street and New Utrecht Avenue in Brooklyn, with the chase ending just north of the 62nd Street station after the train crashed into another train up ahead. The conductor played by Bob Morrone and train operator played by William Coke, aboard the hijacked train were both actual NYC Transit Authority employees. Friedkin’s plan included fast driving coupled with five specific stunts:

- Doyle is sideswiped by a car in an intersection

- Doyle’s car is clipped by a truck with a Drive Carefully bumper sticker.

- Doyle narrowly misses a woman with a baby stroller and crashes into a pile of garbage.

- Doyle’s vision is blocked by a tractor trailer which forces him into a steel fence.

- Doyle must go against traffic to get back on a parallel path with the train. Intercut with these car scenes underneath the elevated train is additional footage (shots facing the car, not from the driver’s perspective) that was shot in Bushwick, Brooklyn, particularly when Doyle misses a moving truck and slams into a steel fence.

The most famous shot of the chase is made from a front bumper mount and shows a low-angle point of view shot of the streets racing by. This was the last shot made in the film and was, according to Friedkin, needed to increase the speed of the chase after a rough cut of the scene proved less impressive than he hoped. While Friedkin contends the front-bumper shot is made at speeds of “up to 90mph,” director of photography Owen Roizman, wrote in American Cinematographer magazine in 1972 that the camera was undercranked to 18 frames per second to enhance the sense of speed. Roizman’s contention is borne out when you see a car at a red light whose muffler is pumping smoke at an accelerated rate. Other shots involved stunt drivers who were supposed to barely miss hitting the speeding car, but due to errors in timing accidental collisions occurred and were left in the final film. Friedkin said that he used Santana‘s song “Black Magic Woman” during editing to help shape the chase sequence; though the song does not appear in the film, “it [the chase scene] did have a sort of pre-ordained rhythm to it that came from the music.”

The scene concludes with Doyle confronting Nicoli the hitman at the stairs leading to the subway and shooting him as he tries to run back up them. Many of the police officers acting as advisers for the film objected to the scene on the grounds that shooting a suspect in the back was simply murder, not self-defense, but director Friedkin stood by it, stating that he was “secure in my conviction that that’s exactly what Eddie Egan (the model for Doyle) would have done and Eddie was on the set while all of this was being shot.”

This gives a measure of Friedkin’s attention to detail in obtaining the most effective shots, but as with all good movies you are so caught up in the moment that the finer points of direction pass you by entirely – as it should be.

For me the earlier scene where Doyle and Charnier are stepping on and off a subway train in their own private game of cat and mouse is riveting cinema.

The fact that these games are led by two of our finest ever screen actors makes a huge difference to the success of the finished product. Rey appeared in over 150 movies and was known primarily for making any character with suaveness and sophistication his own – though in practice he was versatile and authoritative in almost any scenario. Here his smile as Charnier waves to Doyle while the train passes the cop is legendary – a golden moment in movie history (see picture above.)

Hackman was utterly brilliant as the introverted communications expert Harry Caul in The Conversation, but here he is like Caul’s shabby big brother, a deeply flawed individual wedded to his job 24 x 7, and whose pursuits outside involve drinking bourbon and, apparently, being shackled to his bed with his own handcuffs. He lives and breathes thus movie, such that Popeye Doyle will accept nothing short of capturing the haul and arresting the men responsible. Do not get in his way!

The characters are so thoroughly convincing you do well to remind yourself they are only acting, though many are based on real people. Courtesy of Wikipedia:

It tells the story of New York Police Department detectives named “Popeye” Doyle and Buddy “Cloudy” Russo, whose real-life counterparts were Narcotics Detectives Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso. Egan and Grosso also appear in the film, as characters other than themselves. The music score was by Don Ellis. The plot centers on drug smuggling in the 1960s and early ’70s, when most of the heroin illegally imported into the East Coast came to the United States through France. In addition to the two main protagonists, several of the fictional characters depicted in the film also have real-life counterparts. The Alain Charnier character is based upon Jean Jehan who was arrested later in Paris for drug trafficking, though he was not extradited since France does not extradite its citizens; the director credits a general lack of punishment to Jehan’s military service with Charles de Gaulle. Sal Boca is based on Pasquale “Patsy” Fuca, and his brother Anthony. Angie Boca is based on Patsy’s wife Barbara, who later wrote a book with Robin Moore detailing her life with Patsy. The Fucas and their uncle were part of a heroin dealing crew that worked with some of the New York crime families. Henri Devereaux, who takes the fall for importing the Lincoln to New York, is based on Jacques Angelvin, a television actor arrested and sentenced to three to six years in a federal penitentiary for his role, serving about four before repatriating to France and turning to real estate. The Joel Weinstock character is, according to the director’s commentary, a composite of several similar drug dealers.

I have no doubt the research and development work done by actors into their alter egos lends depth and authenticity to the movie, and these factors make for unrivalled watchability. The only thing I found impossible to believe is that the car in which the stash has been transported to the USA has been taken to the police compound, every panel torn from it before the heroin is found, and yet can pass muster as undamaged when the cops give back the car in preparation for the raid. Implausible, to put it mildly!

If you’ve never seen this movie or are put off by the idea of a movie now 42 years old and featuring cars and fashions that look absurd by comparison to today’s preferences, think again. This is worth every second of your time to see how cop movies should be done.