Before we start, I can’t pretend that I’ve seen all Woody Allen films or anything like all of them – but then Allan Stewart Konigsberg is notably prolific, having at the age of 80 churned out over 50 movies as director, quite apart from writing and acting duties (see here), which is an astonishing oeuvre by any standards – particularly if you compare his output to that of perfectionists like Kubrick, for example.

Most of his films are low-ish budget, include a company of actors that have changed over the years but many of whom tend to appear repeatedly. Not a shabby way to establish a career, but even if bears some hallmarks in common with journeymen, Allen’s talent is undeniable – even if he does not appeal to all tastes.

A few examples: I recently saw a batch of early Allen films, all of which are episodic and sometimes run out of steam. One, Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Sex (but were afraid to ask) is a series of 7 sketches, but no less true of Bananas and Sleeper. A friend asked me my favourite vignette of Woody Allen, and I instantly recalled this glorious moment from near the beginning of Deconstructing Harry; it has me in hysterics to this day, though I can remember almost nothing about the remainder of the movie.

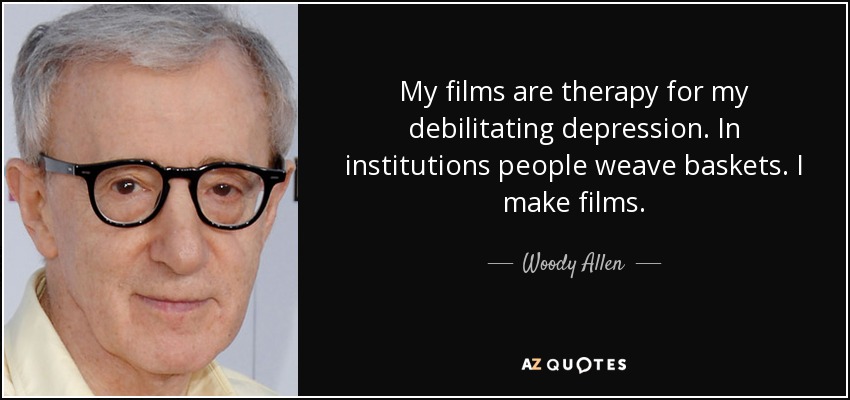

The usual story is that Allen movies, especially those involving Allen the alter ego, are full of whining neuroticism masking the occasional gem – what Scousers call “shining wit.” There’s no denying that Allen used those characteristics knowingly as a metaphor for the east coast intelligentsia, but more particularly by taking large portions of his own persona and therapy dialogue as a way to induce humour, as he admitted himself about his more “self-absorbed” projects.

In Allen’s case, the anguishing is typically on the subject of the many obstacles and pitfalls of relationships, most of which go terribly wrong and seldom seem to have happy endings. Bittersweet maybe, but with much wry humour to be wrung from the topic. When it works, it works brilliantly; when it doesn’t, ennui can set in quickly.

Perhaps this is the real truth of Allen’s pictures: having come from a background as a stand-up comedian and writer for other comedians, he thinks in sketches and develops films as a series of sketches, some of which are as brilliant and/or funny as anything you’ve ever seen, but which don’t sustain the brilliance over the course of a whole movie.

Maybe this is also why Allen’s films are on the short side, typically half the length of the average Tarantino epic; when he sustains the creative urge with a majorly theme across a full 2-3 hours, he will win Oscars by the bucketload and be featured in the lists of greatest pictures.

This is in spite of Allen’s deep-seated urge to be regarded as a “serious director” up there with Bergman (his hero, along with the Marx brothers), Truffaut, Fellini and a number more esteemed European art cinema greats. His most popular films undoubtedly show as much of the Marx Bros influence as Bergman.

You can’t say he’s not tried, though some experiments have gone badly askew. One that does not remotely appeal to me is The Mighty Aphrodite, in which Allen employs a Greek chorus with more than a touch of New York Jewish humour; some critics loved it, Mira Sorvino won an Oscar, but more than anything it told me that Allen, like many of us, loves to be loved but does not always tickle our fancy.

It irks him that he is best remembered for early bittersweet comedies, notably Annie Hall and Manhattan (though probably not that he won awards for Hannah and her Sisters) but it hasn’t stopped him from making a film a year since the early 70s. He possesses a nervous energy and an unfulfilled desire to make the best film possible.

Equally creative is The Purple Rose of Cairo, whereby the hero steps from the screen of a black and white movie to romance an escapist movie addict in the audience, though this is one of many movies that hark back with warm nostalgia to Allen’s Jewish childhood. Radio Days being the most obvious in the way that Terence Davies used music to narrate the fragmented story of his own childhood in Distant Voices, Still Lives.

On the plus side, critics often fail to recognise how technically inventive he has been in many movies. One of my very favourite is the mockumentary Zelig, which was a pioneer in the art of blue screen to add Allen’s “human chameleon” Leonard Zelig to historical newsreel footage with authentic appearance, complete with hilarious fake commentary – a technique later used successfully in Forrest Gump (see a detailed description from Wikipedia below.)

I loved this comparatively minor film because it made a point that we all love to be loved, but then all Allen films have a point behind the humour, even if audiences would prefer to hang on to the jokes. The man is unquestionably highly intelligent and his films are often the result of the torrent of existential ideas running through his head, though his ability to communicate complex and intangible ideas to audiences that mostly want to be entertained has varied.

As he is quoted as saying: “If my films don’t show a profit, I know I’m doing something right.” How wonderful to be in a position to have people financing all your projects, regardless of whether they make money! In fact, he makes a high-grossing film every 2-3 years, which probably help to fund some of the less popular movies made inbetween.

Much has been made of Allen’s complicated private life by the media, of whom the director is understandably mistrusting, though he has often chosen to intertwine his personal and professional lives by casting his partners and even one of his wives (Louise Lasser, Diane Keaton and Mia Farrow in particular) in multiple films. His break-up from Farrow, and subsequent unproven and emotionally damaging accusations of sexual abuse were conducted in the media and the courts. It’s noticeable that since Allen courted controversy by marrying Farrow’s adopted daughter Soon-Yi Previn, Previn has stayed very much out of the limelight.

You certainly get the impression Allen is more stable and contented than at any time in the past, which has been reflected in the more broad-based (ie. often set in Europe, especially London) and less intensely personal film projects he has undertaken in recent years. A film like Vicky Cristina Barcelona would probably not have seen light of day when Allen was mostly cloistered in New York, for example, nor many other more mature and outgoing works.

It feels as if Allen is not trying so hard and is working within himself, and the effect of not striving to push boundaries is felt in films that feel more comfortable to audiences. He has also acted in fewer of the films in recent years, which may or may not be related.

As for what the critics think, I found this list of Allen films rated from worst to best quite fascinating. Whatever the director may think, it’s noticeable that the list is headed by two films from the 80s (Hannah and her Sisters and Crimes and Misdemeanours) and one from the 70s (Annie Hall). It might frustrate Allen, though it’s very noticeable that in those periods he was able to communicate most effectively those fears, dreams and thoughts foremost in the minds of audiences. So let me finish with the lovely quote from the end of Annie Hall:

“After that it got pretty late, and we both had to go, but it was great seeing Annie again. I… I realized what a terrific person she was, and… and how much fun it was just knowing her; and I… I, I thought of that old joke, y’know, the, this… this guy goes to a psychiatrist and says, “Doc, uh, my brother’s crazy; he thinks he’s a chicken.” And, uh, the doctor says, “Well, why don’t you turn him in?” The guy says, “I would, but I need the eggs.” Well, I guess that’s pretty much now how I feel about relationships; y’know, they’re totally irrational, and crazy, and absurd, and… but, uh, I guess we keep goin’ through it because, uh, most of us… need the eggs.”

Allen used newsreel footage and inserted himself and other actors into the footage using bluescreen technology. To provide an authentic look to his scenes, Allen and cinematographer Gordon Willis used a variety of techniques, including locating some of the antique film cameras and lenses used during the eras depicted in the film, and even going so far as to simulate damage, such as crinkles and scratches, on the negatives to make the finished product look more like vintage footage. The film uses cameo appearances by real figures from academia and other fields for comic effect. Contrasting the film’s vintage black-and-white film footage, these persons appear in color segments as themselves, commenting in the present day on the Zelig phenomenon as if it really happened. They include essayist Susan Sontag, psychoanalyst Bruno Bettelheim, Nobel Prize-winning novelist Saul Bellow, political writer Irving Howe, historian John Morton Blum, and the Paris nightclub owner Bricktop. Also appearing in the film’s vintage footage are Charles Lindbergh, Al Capone, Clara Bow, William Randolph Hearst, Marion Davies, Charlie Chaplin, Josephine Baker, Fanny Brice, Carole Lombard, Dolores del Río, Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels, Hermann Göring, James Cagney, Jimmy Walker, Lou Gehrig, Babe Ruth, Adolphe Menjou, Claire Windsor, Tom Mix, Marie Dressler, Bobby Jones, and Pope Pius XI.