- Up to your waist in water,

- Up to your eyes in slush –

- Using the kind of language,

- That makes the sergeant blush;

- Who wouldn’t join the army?

- That’s what we all inquire,

- Don’t we pity the poor civilians sitting beside the fire.

- Chorus

- Oh! Oh! Oh! it’s a lovely war,

- Who wouldn’t be a soldier eh?

- Oh! It’s a shame to take the pay.

- As soon as reveille is gone

- We feel just as heavy as lead,

- But we never get up till the sergeant brings

- Our breakfast up to bed

- Oh! Oh! Oh! it’s a lovely war,

- What do we want with eggs and ham

- When we’ve got plum and apple jam?

- Form fours! Right turn!

- How shall we spend the money we earn?

- Oh! Oh! Oh! it’s a lovely war.

The First World War was and remains an event etched upon our collective consciousness, not far off a Century later – and with good reason. The horror witnessed by those present has died with them, though their accounts can be seen in many places, and I recommend the Imperial War Museum as a fine testimony to the impact of WWI. I remember vividly the stories told to me by my grandfather, who won the Military Cross for saving a gun emplacement but never really spoke about the horrors he saw.

The facts barely do it justice (from Wikipedia):

World War I (WWI or WW1), also known as the First World War or the Great War, was a global war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918. More than 9 million combatants and 7 million civilians died as a result of the war, a casualty rate exacerbated by the belligerents’ technological and industrial sophistication, and tactical stalemate. It was one of the deadliest conflicts in history, paving the way for major political changes, including revolutions in many of the nations involved.

How then to categorise Oh! What A Lovely War? The 1969 movie, like the preceding stage show, is many things, mostly a poignantly satirical and stylised history of what is satirically known as “the Great War”, but I am filing it under musicals for the excellent reason that the narrative, if there is one, is driven by iconic music hall songs of the era, the sort you’ve always known but never necessarily heard in context or for their biting parody or in some cases simple irony.

Many of the motifs come from Joan Littlewood‘s original stage production, notably the end-of-pier show razzamatazz, which reminds me. My connection with the music goes back to school days, when I appeared in a play in which the song I’ll Make A Man Of You, sung in the film by the estimable Maggie Smith. Except in our version, where the music hall singer yells “Come on boys, I need a million!” – the men at the back yelled back “I’ve only got two!”

The film also marked the directorial debut of the great Richard Attenborough and is unquestionably a who’s who of fine British character actors, the sort we churn out by the hundred thanks to our tradition of rep theatre. Don’t believe me? Try this list for size – arguably one of the greatest casts ever assembled, including another epic directed by Dickie, A Bridge Too Far!

- Ian Holm as President Poincaré

- Joe Melia as the Photographer

- Guy Middleton as Sir William Robertson

- Juliet Mills as Nurse

- Nanette Newman as Nurse

- Cecil Parker as Sir John

- Gerald Sim as Chaplain

- Edward Fox as Aide

- Peter Gilmore as Private Burgess

- Dirk Bogarde as Stephen

- John Gielgud as Count Leopold Berchtold

- Jack Hawkins as Emperor Franz Josef I

- Kenneth More as Kaiser Wilhelm II

- Laurence Olivier as Field Marshal Sir John French

- Michael Redgrave as Sir Henry Wilson

- Vanessa Redgrave as Sylvia Pankhurst

- Ralph Richardson as Sir Edward Grey

- Maggie Smith as Music Hall Star

- Susannah York as Eleanor

- John Mills as General (later Field Marshal) Sir Douglas Haig

Composed as a series of vignettes loosely based on the experience of the Smith family during WW1 and shot for the greater part (no pun intended) in, on, by and near the West Pier in Brighton and the South Downs. The sketches begin slowly with the chessboard politics of the pre-war era, where the peace is preserved only by a complex web of alliances that also enabled a single event, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, t0 spiral up to full-scale international war.

From there the action fans out into the heroic mood of young men signing up in a mood for action and the lie that it will “all be over by Christmas.” The new recruits soon find the reality of army life is far worse, but even then nothing could prepare them for life in the trenches, still less for the repeated advances over no-man’s land where some battalions were wiped out almost in their entirety and in defiance of the belief that “one more push” would see the German lines collapse and victory assured as the morale plummets following bombardments and the white eyes of the brave Tommies coming over the top.

In reality the guns fired and they died in their thousands. We see life at war from many perspectives, including the brief respite of Christmas camaraderie between Tommy and Jerry, many of whom died soon after battle recommenced. Meanwhile, the generals are portrayed living on another planet with their dinner-dances and faith in an almighty deity who shows little evidence of compassion – and the role of the padre to reinforce morale and assure the English that God was firmly on their side – much as happened on the German side too.

Finally we move on to the disillusionment as the war ends, Europe is carved up once again and the dead move on to another place – the cricket scoreboard reveals the English dead from the Somme to be 607,000 men and officers, with ground gained nil.

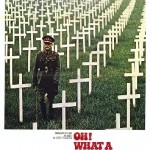

The ending is arguably the most famous and heart-wrenching shot in the film, as the camera pans out on a green foreign field where the Smith women and children play to reveal thousands upon thousands of white crosses as the voices of the dead sing “We’ll Never Tell Them” (a parody of the Jerome Kern song “They Didn’t Believe Me“). Seems no fewer than 16,000 of these were banged into the ground individually, but they didn’t even represent more than a fraction of the deaths in one battle.

The sheer volume of killing in this “great war” was truly unimaginable, yet Haig and French remained defiant by the scale of the slaughter, apparently happy to fight to the last man standing, and equally bemused when the Americans file in to complete a job that really might otherwise have continued indefinitely. “Lions led by donkeys?” The historians might be revising opinions but popular culture has long since decided, albeit in caricature.

In this case, the satire is anti-war but avoiding the cardinal sin of ramming its message down your throat; “wry” would be the mot juste. For all the underbelly of bitterness, this is by no means as savage an attack as many would believe justified by the events. Whatever his many other characteristics, Attenborough was not given to melodrama and was much taken with subtle inference as an effective tool to audience enlightenment ahead of the bludgeoning hammer of many a director. Here he made an important statement, one that needed to be made – less an attack on war as on the hypocrisy of war.

As such OWALW marks a key cornerstone of British cinema history, almost an exorcising of the ghosts or our past – not that it ever stopped the source material of this most dreadful and bloodthirsty war being used. Maybe without Dickie Attenborough’s movie we could not have had that moving finale to Blackadder Goes Forth?

___

The Army and the Navy need attention

The outlook isn’t healthy you’ll admit

But I’ve a perfect dream of a new recruiting scheme

Which I really think is absolutely it

If only other girls would do as I do

I believe that we could manage it alone

For I turn all suitors from me, but the Sailor and the Tommy

I’ve an Army and a Navy of my ownOn Sunday I walk out with a Soldier

Monday I’m taken by a Tar

Tuesday I’m out with a baby Boy Scout

On Wednesday a Hussar

On Thursday I gang out wi’ a Scottie

On Friday the Captain of the crew

But on Saturday I’m willing if you’ll only take the shilling

To make a man of any one of youI teach the tenderfoot to face the powder

That gives an added lustre to my skin

And I show the raw recruit how to give a chaste salute

So when I’m presenting arms, he’s falling in

It makes you almost proud to be a woman

When you make a strapping soldier of a kid

And he says, “You put me through it and I didn’t want to do it

But you went and made me love you, so I did!”On Sunday I walk out with a Bosun

On Monday a Rifleman in green

On Tuesday I choose a Sub in the Blues

On Wednesday a Marine

On Thursday a Terrier from Tooting

On Friday a Midshipman or two

But on Saturday I’m willing if you’ll only take the shilling

To make a man of any one of you!