“I disagree with what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it” (misattributed to Voltaire.)

Freedom of speech is a hallowed and cherished principle in many a bill of rights (1689 in England) and constitution (1st Amendment to the US Constitution) and even enshrined in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the UN General Assembly on 10 December 1948:

“Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

In short, this means every person in a country represented within the General Assembly has a universal right to hold our own opinions and to voice them, to say what we want without fear or favour when we choose to do so, though doing so often requires us to exercise tact and discretion in our social circles – in other words, to voice our thoughts and opinions responsibly. However, a fair and reasonable debate in our society is welcomed and from that spectrum of views others will determine where they stand.

The UDHR is of course only one declaration among many promoting the principle of freedom of speech as a fundamental human and constitutional right, though it is an interesting one given that speech in the public domain is anything but free in a substantial number of countries represented in the UN General Assembly. We are lucky that the voicing of an opinion contrary to the existing government or state does not automatically land use in jail or with a death sentence. You only have to think back to the Tiananmen Square massacre in Beijing in 1989 to realise that the superpower that is China clamps down hard on dissident opinion critical of the Communist Party, and the so-called Arab Spring to realise that the power of enough voices opposing an autocratic regime can effect radical change. Freedom of speech is not necessarily just an individual phenomenon but potentially the voice of a population – free speech extends to everyone in society.

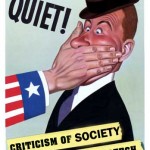

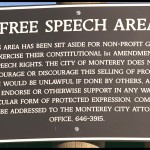

But, and it’s a big but, freedom of speech can never be taken for granted. Jean-Jacques Rousseau is perhaps best known for a quote from his Social Contract: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” And nowhere is this more apparent than in the historical right to “freedom of speech.” Perhaps there were always provisos and restrictions to that right, but what concerns many supporters of the freedoms fundamental to an open society is that the boundaries of free speech are shifting and shrinking. Even that true freedom of speech appears increasingly elusive as social and barriers rise. Can we protect this fragile right against those who would erode it? Like all rights, it is only ever be truly appreciated once it has disappeared for good.

The UK and US have our respective Freedom of Information Acts, to ensure that information is circulated on matters of public interest; we have no secrets from our people, and our people have a right to speak up and ensure our representatives act in our best interests. There is nothing to fear from robust debate, the saying goes. Except that much is censored from the FoIA and further restrictions are being introduced – governments hate freedom of information and would stifle debate if they could. Once elected, they want to govern without the prying eye of public interest, in the form of media investigation.

But saying that, how easy is it to voice unacceptable opinions even in countries where freedom of speech is tolerated? In a democracy some pretty unpalatable opinions must be heard and debates be stated as a basic right – you can’t have it both ways. I don’t agree with anything the BNP says, but I don’t agree with people who would deny the party that voice, providing they do not use it for inciting racial hatred. In the UK, several people have been jailed recently following tweets, though these have mostly concerned incitement to hatred, particularly racial hatred. The line is drawn in freedom of speech where the law is broken, and in the case of the new law that line prevents

Remember too that the USA is the country which conducted its own witch hunts in the form of the 1950s McCarthyite trials, after Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin – the quintessential denial of freedom of speech to Americans. If McCarthyism means “the practice of making accusations of disloyalty, subversion, or treason without proper regard for evidence,” Americans forgot the 1st amendment right to freedom of belief in those days.

But has that changed in the 21st Century? Very few Americans would tolerate anybody from outside the USA being critical of American society, even when they themselves are critical in their own environment; and try being critical of Christianity in the bible belt, or almost any other part of the country. It’s impossible for anyone not declaring themselves to be Christian to be elected President, or indeed any other public office. And even now, “socialism” is a term of abuse in the country, even though very few understand its actual meaning.

Speaking against governments and organisations is one thing – and both have many ways to restrict our ability to do so effectively, but do we have the same rights to speak critically of any individual in our society? Arguably not, even when our facts are truly fact. The most widely-utilised restrictions are laws of defamation, namely slander and libel: if anyone believes their reputation has suffered as a result of the publication in any form of untruths, they can sue in the civil courts. Within the UK, the law of libel turns natural justice on its head by putting the burden of proof on the defendant. From Wikipedia:

“In most legal systems, the courts give the benefit of the doubt to the defendant. In criminal law, he or she is presumed innocent until the prosecution can prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt; whereas in civil law, he or she is presumed not liable until the plaintiff can show liability on a balance of probabilities. However, the common law of libel reverses the traditional positions somewhat: a defamatory statement is presumed to be false, unless the defendant can prove its truth. One could suggest that this amounts to a presumption of the innocence of the plaintiff in the face of an accusation levelled by the defendant. Furthermore, to collect compensatory damages, a public official or public figure must prove actual malice (knowing falsity or reckless disregard for the truth). A private individual must only prove negligence (not exercising due care) to collect compensatory damages. In order to collect punitive damages, all individuals must prove actual malice. The definition of “public figure” has varied over the years.”

So if “a claim of defamation is defeated if the defendant proves that the statement was true” the real issue is that the statement may well be totally true but cannot be proven since the “public figure” has secreted all the evidence and does not have to prove the claims to be false.

This may be to protect the innocent from having to disprove a negative, and protection against lies being circulated is fair and reasonable, but the practical impact of how the law is currently worded is to allow the rich and powerful to sue for libel and win swingeing damages against investigations by media sources into illegal activity by the tycoons concerned. You only have to think of Robert Maxwell and Conrad Black to realise that the libel laws helped perpetuate gross falsehoods for which one was eventually jailed and the other should have been, but for his death. There are many more examples of the law being on the side of the guilty too. The one that springs to mind is that of MP Jonathan Aitken. This section of Aitken’s Wikipedia entry deserves quoting in full:

“On 10 April 1995, The Guardian carried a front-page report on Aitken’s dealings with leading Saudis. The story was the result of a long investigation carried out by journalists from the newspaper and from Granada TV‘s World In Action programme. Aitken had called a press conference at the Conservative Party offices in Smith Square, London, at 5 o’clock that same day denouncing the claims and demanding that the World In Action documentary, which was due to be screened three hours later, withdraw them. He notoriously said:

- “If it falls to me to start a fight to cut out the cancer of bent and twisted journalism in our country with the simple sword of truth and the trusty shield of British fair play, so be it. I am ready for the fight. The fight against falsehood and those who peddle it. My fight begins today. Thank you and good afternoon.”

The World In Action film, Jonathan of Arabia, went ahead and Aitken carried out his threat to sue. The action collapsed in June 1997 (a month after he had lost his seat in the 1997 General Election) when the Guardian and Granada produced, via their counsel George Carman QC, evidence countering his claim that his wife, Lolicia Aitken, paid for the hotel stay at the Ritz Hotel in Paris. The evidence consisted of airline vouchers and other documents showing that his wife had, in fact, been in Switzerland at the time when she had allegedly been at the Ritz in Paris. The joint Guardian/ Granada investigation indicated an arms deal scam involving Aitken’s friend and business partner, the Lebanese businessman Mohammed Said Ayas, a close associate of Prince Mohammed of Saudi Arabia. It was alleged that Aitken had been prepared to have his teenage daughter Victoria lie under oath to support his version of events, had the case continued.“

A few days after the libel case collapsed, World In Action broadcast a special edition, which echoed Aitken’s “sword of truth” speech. It was entitled The Dagger of Deceit. During this time it emerged that when Aitken was being encouraged to resign, he was chairman of the secretive right wing think-tank Le Cercle, alleged by Alan Clark to be funded by the CIA.“

Aitken was charged with perjury and perverting the course of justice, and in 1999 was jailed for 18 months, of which he served seven. During the preceding libel trial, his wife Lolicia, who later left him, was called as a witness to sign a supportive affidavit to the effect that she had paid his Paris hotel bill, but did not appear. In the end, with the case already in court, investigative work by Guardian reporters into Swiss hotel and British Airways records showed that neither his daughter nor his wife had been in Paris at the time in question. To date, Aitken is the only British Cabinet minister ever to have been sent to jail.”

In short, it was only at the 11th hour that evidence was found by the Guardian to prove Aitken was lying through his teeth, but for which the MP would have won substantial damages. “Bent and twisted journalism” was in this case vindicated, but it does make you wonder how many times libel cases are won by people whose relationship with the truth is at best tangential.

Ah, but you will remember that for it to be defamation there has to be malice, against which is the “fair comment” defence – surely the cornerstone of free speech:

This defence arises if the defendant shows that the statement was a view that a reasonable person could have held, even if they were motivated by dislike or hatred of the plaintiff. The fair comment defence is sometimes known as “the critic’s defence” as it is designed to protect the right of the press to state valid opinions on matters of public interest such as governmental activity, political debate, public figures and general affairs. It also defends comments on works of art in the public eye such as theatre productions, music and literature. However, fair comment and justification defences will fail if they are based on misstatements of fact.

This story struck me as a gross injustice, allowing powerful politicians to wield a huge sledgehammer to crack the nut of a not unreasonable tweet probably seen by just a few people that could be laughed off and forgotten, and which is quite probably true. To quote from the article:

On 20 October, he (Ravi Srinivasan) posted a tweet to his 16 followers saying that Karti Chidambaram, a politician belonging to India’s ruling Congress party and son of Finance Minister P Chidambaram, had “amassed more wealth than Vadra”. He was alluding to Robert Vadra, son-in-law of Congress party chief Sonia Gandhi, who was at the centre of a political row after allegations over his links with a top Indian property firm. Mr Vadra denies the charges.

Jailing Ravi Srinivasan for what is essentially fair comment is a vicious twist in the freedom of speech saga. New rules are being established for online publication, even in tweets, that are even more draconian than ever known before. Why? The argument goes that tweets can go viral in seconds, and that anybody reading them would apply “no smoke without fire” logic. As Gertrude in Hamlet so eloquently puts it, “methinks the lady doth protest too much.”

I don’t believe for one second that the two people mentioned by Mr Srinivasan are entirely innocent of the implied charges of having used their respective offices for personal financial benefit, but that many people did believe that is indicated clearly by the vast support group that has grown up in no time. Yet the new law still allowed the poor chap to be jailed without a fair trial or the people concerned having to demonstrate the falsehood of the remarks. Is this justice? Freedom of speech it certainly ain’t!

And of course the flipside to all of this relates to Twitter and its like: messages on the internet can go instantly viral. False and fabricated allegations will go around the world in seconds and will often be believed, which is how cases like the one implying the involvement of Lord McAlpine in child abuse and the subsequent Newsnight reference to this allegation by one victim -apparently mistaken identity – came about. By its very nature, you can’t police the Internet, but how and when the law should take effect to protect, if indeed it is the best weapon, is not clear. The law operates in hindsight, and any form of prevention in the form of vetting material before it goes live would clearly be impossible with sites like Twitter or Facebook. But whatever the answer is, censorship is not it.

Most allegations can and should safely be ignored, unless and until they reach the form where a person’s reputation has been trashed or a police investigation ensues, but I’d suggest that if people in office take offence at valid opinions on non-personal topics stated without malice (and most libels are probably not committed in malice for definitions outside the law), they should not be in office. Anyone in public life should be completely open about their affairs (literally and metaphorically) and be prepared to accept intrusive questions without punishing those who dare to ask them.

One aspect of this debate has of course been discussed at length in the UK phone hacking scandal and the subsequent Leveson enquiry. The press hacking the phones of celebrities, politicians and ordinary people alike to get stories is of course illegal and immoral, though those who would stifle freedom of speech would also like a privacy law. Even whistleblowers are finding it tough, and there are supposedly codes to protect their rights too.

There is a balance to be struck, but with the libel laws unchanged, FoI less accessible and fewer legal options used to delve into hidden scandals, the likelihood is that more items that are within the public interest will be exposed. And anyone voicing an opinion without proof is likely to meet short shrift. The result of this kind of intolerance to free speech is that the likes of Jimmy Savile can get away with breaking the law with impunity over many decades – because we as a society wimped out of our right to free speech and let him. It is our job to hold to account people in our society to ensure that they stay within the acceptable limits we impose, and do not abuse their position.

The price of freedom of speech is that things will be said some people don’t like. So be it.

PS. Charlie Brooker‘s view of the rules of Internet use. Enjoy!

Should be straightforward. You don’t even have to go outside. Just sit at home methodically typing the most grotesque and inflammatory statements you can think of, rounding off each post with a link highlighting your precise co-ordinates on Google Maps. Start at 10am and, providing you have been provocative enough, a self-righteous mob should be sawing your head off and kicking it around like a football by teatime. Think of it as a crowd-sourced version of Dignitas. There are less physically agonising ways to die, yes – but this is one of the easiest.

And it’s not a far-fetched scenario: last month, a teenager went on Facebook and posted a string of tasteless jokes about a recent child murder. Before long, a 50-strong “vigilante mob” turned up at his home address. He was arrested – apparently for his own safety – and then jailed. Hang on, I’ll just type that last word again in capitals: JAILED.

n recent weeks we have been dealing with the side-effects of hyper-connectivity, and it’s not pretty. When whoever invented Twitter invented Twitter, they could surely have never conceived that their precious brainchild might ultimately lead to Philip Schofield handing a list of suspected paedophiles to the prime minister on daytime television, in what I, for one, was hoping would become a regular new This Morning “format point”, inbetween the Milf makeovers, celebrity interviews, and the occasional headline-grabbing interludes where they get someone to drop their pants to raise awareness of bum mumps or something.

And of course it’s not just Schofield who’s in trouble. Last week, thousands of Twitter users presumably rushed to their keyboards to frenziedly delete anything they had ever said or implied about Lord McAlpine, desperately trying to mop up any evidence of gossip before his legal team could harvest their details as part of The Biggest Libel Case Ever. It’s safe to assume that none of these users contemplated the possibility of being sued by a peer of the realm when they originally signed up to the service but nonetheless, for good or ill, that’s where they find themselves.

Rule No 1 is: don’t form a mob on the basis of anything you read less than a minute ago.

Rule No 2: accusations of child abuse don’t go down very well, even if you try to “lighten the mood” midway through them by typing LOL.

And rule No 3 is: don’t be a dick.

Can someone recommend Penis Dildo? Cheers xx

By way of introduction, I am Mark Schaefer, and I represent Nutritional Products International. We serve both international and domestic manufacturers who are seeking to gain more distribution within the United States. Your brand recently caught my attention, so I am contacting you today to discuss the possibility of expanding your national distribution reach.We provide expertise in all areas of distribution, and our offerings include the following: Turnkey/One-stop solution, Active accounts with major U.S. distributors and retailers, Our executive team held executive positions with Walmart and Amazon, Our proven sales force has public relations, branding, and marketing all under one roof, We focus on both new and existing product lines, Warehousing and logistics. Our company has a proven history of initiating accounts and placing orders with major distribution outlets. Our history allows us to have intimate and unique relationships with key buyers across the United States, thus giving your brand a fast track to market in a professional manner. Please contact me directly so that we can discuss your brand further. Kind Regards, Mark Schaefer, marks@nutricompany.com, VP of Business Development, Nutritional Products International, 101 Plaza Real S, Ste #224, Boca Raton, FL 33432, Office: 561-544-0719

Is anyone here in a position to recommend Urethral Sounds? Thanks xox

Has anyone shopped at That Vape Shop Ecigarette Shop located in 2637 W. Cumberland Street?

where to buy cbd oil in springfield missouri