If you’re going to profile an infamous politician, especially a notorious despot like Idi Amin, in a dramatised movie weaving fiction with reality, you have to take a voyage around them and portray them for everything they were. Caricaturing them as evil monsters is easy as taking pot shots at a barn door, but providing a rounded view of a complex and paranoid man is much harder. It’s been done with Hitler, but most viewers would only see the dictator that ordered “the final solution”, not the man inside. This is important because the contrast between a peaceful domestic life and the extremes to which a man can fall is the most shocking moment of all.

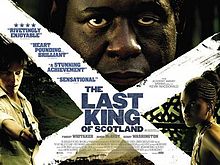

Everyone knows the vicious thug in Amin, but few will be as keen to see the charming, charismatic soldier, a man who for a time united his nation and appeared to be fair, honest and decent. His descent into madness, paranoia and killing friends and enemies alike is well documented, his crimes are the stuff of legend, so what was it that inspired Kevin MacDonald to adapt and film Giles Foden‘s novel about Amin, The Last King of Scotland? And more to the point, how did he wring from the process a very decent performance from James McAvoy and a truly astounding one from Forest Whitaker?

McAvoy plays the fictional Dr. Nicholas Garrigan, a white Scottish medic working in Uganda who, through a chance meeting, ends up as friend and personal physician to Amin and family just at the point when Amin’s coup results in the overthrown of the government of Milton Obote. Why the trust? Good medical advice, but there is more (courtesy of Wikipedia):

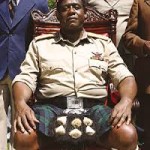

“Amin, fond of Scotland as a symbol of resilience and admiring the Scottish people for their resistance to the English, is delighted to discover Garrigan’s nationality and exchanges his military shirt for Garrigan’s Scotland shirt.”

Ultimately, Garrigan becomes an adviser on health and other issues to the dictator, but makes a huge mistake by becoming a lover to one of Amin’s wives, Kay, and by making her pregnant. From that moment onwards, his card is marked; he cannot escape torture but does manage to flee the country and return to the UK during the Entebbe hostage crisis in 1976.

Garrigan is an everyman observer, he could be anyone. He sees what is going on. At first he accepts it, then he goes through the stages of denial and fear, confrontation and ultimately outright indignation before he realises that his own position is far from secure. In that respect he was like very many more innocent Ugandans who eventually fled from persecution. Garrigan’s Asian tailor is expelled, as were very many more Ugandan Asians, many to these shores.

That much is the work of the scriptwriters, inventing a character to demonstrate the true horrors of reality. The backdrop of the Amin regime and the country at that time is recreated with a fine eye for detail. But what makes the movie work is Whitaker’s staggering portrayal of the man himself. Rarely has an actor dominated the screen so completely, you dare not take your eyes off him. But there is much, much more, notably the sheer volatility of Amin’s moods, leaving all around him eternally on a knife-edge. When Whitaker is on the screen, there is danger, a real sense of danger that communicates itself into the body language of all characters on screen and translates into audience fear and tension. The man is larger than life in every sense of the words.

Amin could do the rabble-rousing, he could be the statesman, the family man, eternally generous to those he considers loyal. One minute he would be laughing and joking, but he could turn on a sixpence to become the most brutal and vicious enemy any man could wish to have. You never knew what you would get, since in essence this was a naive, innocent man, one who reacted to the moment. “You’re a child. That’s what makes you so fucking scary,” says Garrigan to Amin, grinning defiance.

Amin then kicks him hard, before ordering his chest to be pierced by meat hooks, then for Garrigan to be raised on ropes attached to the hooks. There are no punches pulled here; shocking scenes depict just what it was like to cross Amin, and the result was not a pretty sight. The fate of the wife who dared betray Amin is worse in the movie, though I did hear the story that her legs and arms were swapped is purely myth. It was the sort of story that suited Amin for people to tell.

If you haven’t seen it already, see this movie. But be warned – it is not for the squeamish.