Here is one movie you could never remake, firstly because all the subtle, silent unspoken passion would be lost and secondly the expectations of studio heads and audiences alike would be of non-stop illicit bonking.

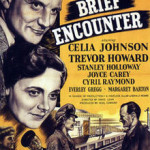

Make no mistake, David Lean‘s Brief Encounter is a cinematic classic for the right reasons – a moving, intelligent, finely crafted tale, bittersweet but romantic in its depiction of an unconsummated love affair between two strangers, simultaneously passionate and innocent, but acted with understated sympathy by Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard. They are supported by a fine cast of British character actors, but what sets this movie apart is not just the emoting but its ground-breaking innovation.

The movie is shot in breathtaking monochrome, replete with striking contrast that is hugely effective at capturing the mood of the provincial station in the era of steam, particularly at night – almost in film noir style (compare to The Third Man, for example.) It makes memorable and pioneering use of Rachmaninov’s celebrated Piano Concerto no 2, not to mention Noel Coward‘s subtle screenplay, bringing to the screen the full intensity and claustrophobia of middle class life in the 40s.

The whole is way more than the sum of the parts, told in flashbacks and teasing apart the emotions of each character without schmaltz or complication, and is infinitely better for the downbeat style and avoidance of the sort of cringeworthy happy ending that might have been tacked on had the film been made in Hollywood.

What makes it such a success is its essential simplicity. Lean rightly pared the ingredients and the storyline down to a bare minimum but used them to build both rapport and emotional intensity, through to the dramatic finale – tear-jerking in its impact but spare in the telling. The bittersweet feelings are left to speak for themselves.

Critics describe Brief Encounter as dated, not only in the eloquent use of 1945 England lifestyle as a backdrop, notably the railway station, but also the mannered performances. To concentrate on Laura Jesson’s middle class lifestyle and Johnson’s accurate portrayal of the character’s social status and language is to ignore the growing sense of desperation, such as when Dolly talks while Laura considers her own fate. In depiction of emotion and the fragility of characters torn apart by love, Brief Encounter is timeless and has not dated one second from when it was made.

This from Wikipedia tells it so well:

In her book Noël Coward (1987), Frances Gray says that Brief Encounter is, after the major comedies, the one work of Coward that almost everybody knows and has probably seen; it has featured frequently on television and its viewing figures are invariably high.

“Its story is that of an unconsummated affair between two married people [….] Coward is keeping his lovers in check because he cannot handle the energies of a less inhibited love in a setting shorn of the wit and exotic flavour of his best comedies [….] To look at the script, shorn of David Lean’s beautiful camera work, deprived of an audience who would automatically approve of the final sacrifice, is to find oneself asking awkward questions” (p. 64–67).

Gray acknowledges a common criticism of the play: why do the characters not consummate the affair? Gray argues that their problem is class consciousness: the working classes can act in a vulgar way, and the upper class can be silly; but the middle class is or at least considers itself the moral backbone of society – a notion whose validity Coward did not really want to question or jeopardise, as the middle classes were Coward’s principal audience.

However, Laura in her narration stresses that what holds her back is her horror at the thought of betraying her husband and her settled moral values, tempted though she is by the force of a love affair. Indeed, it is this very tension which has made the film such an enduring favourite.

The values which Laura precariously, but ultimately successfully, clings to were widely shared and respected (if not always observed) at the time of the film’s original setting (the status of a divorced woman, for example, remained sufficiently scandalous in the UK to cause Edward VIII to abdicate in 1936). Updating the story may have left those values behind and with them vanished the credibility of the plot, which may be why the remake could not compete.

The film is widely admired for the beauty of its black-and-white photography and the atmosphere created by the steam-age railway setting, both of which were particular to the original David Lean version.

The film was a great success in the UK and such a hit in the US that Celia Johnson was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress.

The film was released amid the social and cultural context of the Second World War when ‘brief encounters’ were thought to be commonplace and women had far greater sexual and economic freedom than previously. In British National Cinema (1997), Sarah Street argues that “Brief Encounter thus articulated a range of feelings about infidelity which invited easy identification, whether it involved one’s husband, lover, children or country” (p. 55). In this context, feminist critics read the film as an attempt at stabilising relationships to return to the status quo. Meanwhile, in his 1993 BFI book on the film, Richard Dyer notes that owing to the rise of homosexual law reform, gay men also viewed the plight of the characters as comparable to their own social constraint in the formation and maintenance of relationships. Sean O’Connor considers the film to be an “allegorical representation of forbidden love” informed by Noël Coward’s experiences as a closeted homosexual.

The British play and film The History Boys features two of the main characters reciting a passage of the film. (The scene portrayed, with Posner playing Celia Johnson and Scripps as Cyril Raymond, is in the closing minutes of the film where Laura begins, “I really meant to do it.”)

Kathryn Altman, wife of director Robert Altman said, “One day, years and years ago, just after the war, [Altman] had nothing to do and he went to a theater in the middle of the afternoon to see a movie. Not a Hollywood movie: a British movie. He said the main character was not glamorous, not a babe. And at first he wondered why he was even watching it. But twenty minutes later he was in tears, and had fallen in love with her. And it made him feel that it wasn’t just a movie.” The film was Brief Encounter.

Warmly recommended to anyone who has not seen it. Be warned – you will weep, no matter how many times you see it!