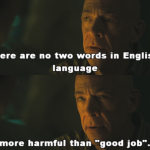

“There are no two words more harmful in the English language than ‘Good Job'” – Terence Fletcher (JK Simmons)

Remember Jonathan Kimble Simmons, AKA film and TV actor JK Simmons? If you do, you’ll probably remember him as a nice guy, for that is how his Hollywood stereotype has worked this past decade or more. Surely you remember the affable dad in the charming and sassy Juno? In fact, wherever you saw his face I bet it had a smile on the face and a twinkle in the eye, for JK always played amiable characters, and did it extremely well.

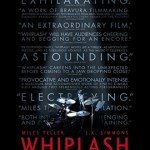

However…. in 2014 it was No More Mr Nice Guy, and it sure as hell paid off for JK – he won best supporting actor for a monumental performance as a bully of a conductor in Whiplash. Musical conductor, that is, for this is a film about a talented jazz band player being abused into playing above and beyond his capabilities, in a way that reminded me how jazz legends in the past have been accused of being lousy human beings – of which more later.

Damien Chazelle wrote Whiplash based on his own experiences in the Princeton High School Studio Band, but the fact is that this tells a universal tale. Simmons’s character, Terence Fletcher, could have been a platoon sergeant major (remember R Lee Ermey‘s terrifying performance in Full Metal Jacket?), football coach, pretty much any sort of leader you care to name where the man in the hot seat has to dragoon his troops to delivering the goods and coming out on top against the odds.

The top coaches will always tell you that there is the winner and the rest are also-rans. For Fletcher perfection is the only option, and he will not settle for anything less, even if it means bawling at a terrified trombonist. Respect is one thing, but if you want to win then a touch of the Alex Ferguson “hair dryer treatment” may just invoke fear of the consequences of failure and concentrate the mind of the team. Either you can step up to the mark or you will be booted into touch, and why? Because mediocrity is simply not acceptable.

Of course, no coach can operate without his players, some of whom must be dedicated above and beyond the call of duty if they are going to make the grade. Fletcher in the film tells how Charlie Parker came back after the upset of drummer Jo Jones throwing a cymbal at him. He practised til he got it right, and returned to become one of the legends. That practice was apparently 15 hours a day for 3-4 years until he mastered improvisation and effectively founded bebop jazz in the process.

This gruellingly intense story concerns how ambitious Andrew Neiman (Miles Teller) overcomes every handicap to take on Fletcher and make the grade. At first his victories are small ones, working at a part and getting the nod over the competing drummers for the core seat, playing at the contest when the first seat does not know the drum part of Whiplash by heart.

But it is hard work, more than hard work – it is excruciating! Cruel mind games are played at every turn to separate the wheat from the chaff, and every mistake is punished – “not my tempo” and not recognising the nature of your fault is the worst error of all (“are you rushing or dragging?”) Nothing less than perfection is acceptable, and since the drummer keeps time his role is critical. The penalty for repeated mistakes is ritual humiliation and potential banishment, but the Fletcher’s potential for cruel and unusual punishments knows no limit – including lying to put himself in a better light.

Neiman practises til his hands bleed and giving up everything in his life, girlfriend included, in the hope, the dream of becoming one of the greats, culminating in a rush to get his drumsticks and make it back in time to play – during which journey his car is horrifically hit by a truck. Does that put him off? Not a bit of it – bloodied but unbowed, Neiman grabs his sticks and runs to the venue, only to be handicapped by a broken finger and to lose a stick.

For this failure his drum career is ended by Fletcher… and he testifies anonymously against the band leader after it is revealed that a former student hanged himself, having suffered anxiety and depression after joining Fletcher’s class. The news of Casey’s death is the closest Fletcher gets to emotion, though even then he does not admit the truth – he claims Casey died in a car accident.

Dismissal could have been the end of Fletcher, except that Neiman meets his former mentor by chance in a jazz club, where Fletcher is playing piano in a jazz quartet. Following this meeting Neiman is given one more chance to play in a big band, only for the ultimate humiliation to follow.

Does Neiman give in? Does he hell! He comes back to take his revenge on Fletcher in the only way he knows how – by playing the drum solo of a lifetime – which Teller played himself (see here and here.) That’s method acting for you! More to the point, it is Neiman’s Parker moment, a drum solo worthy of Buddy Rich, Gene Krupa and Jo Jones.

Chapelle’s direction, geared mostly to fly on the wall cinema verité, works a treat, and arguably far better than in Suffragette. It gives Simmons and Teller time and space to build their characters, and to deliver a rarely achieved level of intensity. Certainly nothing of the “that’s good enough” about the action. This is and inspirational portrayal of the debate of the conflict between good and great, and the insanity of how to transcend the boundaries and go beyond all parallels.

To become a legend, to achieve greatness, that legacy lasts forever. Charlie Parker died at 34, his body broken and sacrificed at the altar of greatness. Neiman in the film does everything but sell his soul to the devil, but ends on the ultimate triumph, much as Teller does in playing him. Very many would not reach that stage, but Chapelle coaxes greatness from his cast.

As the paradox of Whiplash, perhaps Simmons had to go through something of the same process to drive himself to deliver a performance so rich and burning that the Academy were shocked into submission. Whatever drove it, this is assuredly the performance of a lifetime, one that can never be repeated and will certainly not be forgotten. This is a true masterpiece of film acting, one that deserves to be seen by everyone who appreciates the difference between OK and pushing the outer limits.

Oh, and the bandleader with one of the blackest reputations as a tyrannical bandleader also happened to be arguably the greatest jazz drummer of all time, none other than Buddy Rich. I’ll leave you to decide whether Rich’s dedication to excellence in the drums and the tightness of his band paid dividends; here he is his “impossible drum solo” and here he is with his band at the Montreal Jazz Festival.