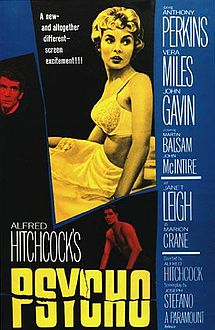

No doubt about it, Psycho is now a classic movie, one of Hitchcock’s finest and certainly his best known movie, but it was not always thought of as a great movie. Indeed, in 1960 it was viewed by many as the source of the demise of the master of suspense, as told in the recent movie Hitchcock.

The main reason for the controversy was the fact that Hitch deliberately pushed the boundaries in every way he could: glimpses of nudity – very tame by today’s standards, but at a time when the censors still had to give their seal of approval to every movie launch; horror and (implied) violence (Crane is decapitated in the book!); the voyeurism, also confronted in Peeping Tom in the same year; transvestism (which to studio bosses meant Bates was “queer”) and multiple personality disorder; the Oedipus Complex portrayed in the obsessive relationship between Bates and his mother; and, most revolutionary of all, tampering with the golden rules of dramatic narrative structure in ways that were a total anathema to the Hollywood studio heads. Nobody, but nobody kills off their leading lady 30 minutes into the picture, even if she is an anti-heroine. Why would you do that?

Put simply, they did not understand it and foresaw only disaster. For them, North by North West was a success since it set the tills ringing and because critics were very positive, whereas for Hitch it was a failure. Some whispers even suggested the master was past his best and should retire at the top. Psycho was his inevitable response – two fingers up to the system, but evidence that he could still get to audiences like few other directors. And more to the point, he was arguably the first director of note to avoid the cardinal sin of underestimating the intelligence of the audience by dumbing down the picture to the lowest common denominator, and also the first to give them macabre inky black humour of the type that went right over the heads of the old school.

At the time the shock value counted for everything, but 53 years on the movie is every bit as watchable as it was then, despite the story and its secrets being known by everyone. This is because Hitch crafted and cut his movies better than almost any director. He had his own rules of suspense and he stuck to them, deliberately to manipulate the emotions of audiences. You can and should be taken in by the story, but there is so much more to admire that justifies a second, third or fourth viewing. Little details and symbolic motifs you never spotted can be picked up next time around, evidence the maestro left nothing to chance, and marshalled the ingredients to perfection. He had many imitators, though few were so idiosyncratically unique, and few could escape his legacy and stand on their own terms as innovators.

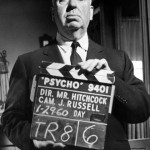

Indeed, everything about this movie is innovative. The cinematography and camera angles, a study in black and white, went places few other movies had ever gone, as discussed in this study guide about the movie; the musical score by Bernard Hermann, who once wrote film and radio scores for Orson Welles, was startling and creepy and very definitely an integral part of the action – it shaped the musical backdrop to horror movies for decades thereafter; the shower scene has become legendary, especially the editing, without direct exposure to nudity or violence; and so on – everywhere you look there is something to watch. In fact, the whole ambience became so iconic that the Bates house has become embedded in modern culture.

The story alone is fascinating, starting as it does with a love affair, a spontaneous theft and a flight out towards California by Marion Crane, a journey she would never complete. Is her death at the hands of the psychologically disturbed Norman Bates merely a case of justice being served? Surely not because she had every intention of returning the money and handing herself in. Besides, Norman never actually finds the money – his motives relate solely to his mother’s jealousy. There is much to interpret here and many possible views you could take of the movie’s morality. Hitch would not have cared so long as there was a buzz, and he was rewarded for his efforts many times over – though not by the Academy.

Equally, you might say there are subconscious undertones of Hitch’s own psychology within the movie, quite apart from his obsession with blonde leading ladies. I’ve long believed the characters are made to play out different aspects of Hitch’s complex and multi-faceted persona, much as authors often create characters to represent parts of their own ego. Selection of cast therefore became critical, and in Janet Leigh and Anthony Perkins he chose and tormented performances from actors who had their own crosses to bear. The fact that Perkins was obsessed with his own mother, suffered the death of his father aged 5, felt tremendous guilt, and was by nature as twitchy as his alter ego, was by no means coincidental to his casting. Perkins did not merely play Norman Bates, he WAS Norman Bates.

Finally, the description in the learning guide to Psycho, linked above. I think it sums up the film pretty well, but you may want to form your own opinion – do watch again and see what happens next time around!

Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho was first screened in New York on 16 June 1960. It was an immediate box-office success. From the start, expectant filmgoers began queuing in Broadway at 8.00am setting a pattern for audiences worldwide. By the end of its first year, Psycho had earned $15 million – over fifteen times as much as it cost to make.

Psycho was a watershed in many ways. As well as making Alfred Hitchcock a multimillionaire, it was to win huge critical acclaim and enshrine him as a master filmmaker. It generated two sequels itself and set down a formula for ‘madman with knife’ films, shamelessly copying its film techniques. It also influenced the makers of many of the most well-known modern horror and suspense films, ranging from Halloween to Fatal Attraction.

Psycho’s commercial success was due, in part, to a superbly orchestrated publicity and marketing campaign that set new standards for audience manipulation. Hitchcock insisted people alter their cinema-going habits if they wished to see his film, and in doing so, he helped create film-viewing conventions that we now take for granted.

It is claimed that the film reflected, or contributed to, a growing permissiveness in society: its violence, sexual content and even the flushing of a toilet on screen, all breaking new ground for mainstream Hollywood film. Its themes struck at many cherished American values; mother love, in particular, would never be quite the same again. Following its release, Psycho was even blamed in court for being the cause of a number of horrible murders, stimulating a debate about the links between screen violence and anti-social behaviour that continues unabated to this day.

PS. Interesting clips on the making of Psycho and the shower scene in particular.