Stanley Kubrick was of course a genius and quite possibly a madman too. Not a genius beloved by actors (like Hitchcock, he treated them worse than cattle), nor always critics. He did not make many movies, but those he did make were hand-crafted by a total perfectionist who would accept nothing less than his vision being recreated to the finest possible outcome – and even then he would tinker with it for months, post-production. Some might now appear dated, convoluted, baffling, even stylised to the point where they are barely watchable; but leaden they are most certainly not, and in the creation process few movies have ever been more thoroughly thought through.

A Kubrick picture is intricate, complex, mannered, and everything, but everything, is done for a reason – even if that reason is far from readily apparent. Kubrick’s genius lay in his minute attention to detail, technical and visual, where the focus on the art is infinitesimally vital but the attention of the audience, the views of the studio and the sale of tickets is an afterthought. For that alone the man deserves massive admiration, for almost nobody is now allowed to make a movie without compromise, not even the masters.

Like Hitch, he would talk with technicians for hours about the details of which lens was required for which shot (a Zeiss lens made for NASA in order to get the right effect of candlelight for Barry Lyndon, innovative use of Steadycam for The Shining), because otherwise the effect would simply fail the test.

The genre was not important (you name the category of subject matter, Kubrick found source material to film it from a unique angle), but control of every aspect of the finished product was, for Kubrick, vital, and he did not welcome any interference with any aspect of his work. Brutal, iconoclastic, ever controversial (eg. Nabokov‘s Lolita adapted for the big screen in 1962) – love him or hate him, Kubrick’s work could never, ever be ignored.

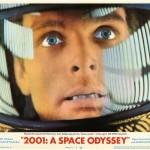

It was tempting to talk about A Clockwork Orange, given the movie’s chequered and fascinating history, but as an introduction to the great man I can do no better than his adaptation of Arthur C Clarke‘s short story The Sentinel (Clarke’s novel of the same name was published after the film was released) into a sprawling 2 hour 20 minute epic 2001: A Space Odyssey, constructed in four distinct acts within the one movie and leaving a sense of ambiguity that mystified audiences and staged a massive leap forward in the scifi genre.

The act everyone remembers is set in the space station, notably the section set to Johann Strauss II‘s Blue Danube and filmed with an elegance and finesse worthy of a Swan Lake – a ballet in space. Then there is the truly haunting moment when the spookily-voiced rogue computer HAL 9000 is switched off and grinds to a halt while singing Gracie Fields‘s immortal Daisy Bell, and of course the momentous opening to Richard Strauss‘s Also Sprach Zarathustra, chosen with a strong nod to the original work by Nietzsche. The rival apes killing a member of the opposite tribe attracted attention too. Even if you don’t follow the loftier themes, there is always much to be imprinted indelibly on your mind.

But this is far more than merely an abstract and minimalist space movie, it is a masterpiece of ideas on a grand scale, an epic multimedia symphony of colour, light and sound; a philosophical debate on the nature of human existence and evolution and artificial intelligence; a ground-breaking tour de force every bit as significant to the industry as Welles‘s Citizen Kane was in its day.

In some ways actors are almost robots here, components like props to be manipulated – and I don’t suppose that was remotely accidental. The only true humanity on show is William Sylvester‘s Dr Heywood Floyd talking to his young daughter from the space station to wish her a happy birthday. Some are there are almost farcically, like Leonard Rossiter with a vaguely Russian accent. They are what they represent, such as ape man “Moonwatcher” (Daniel Richter) smashing the bones of dead animals in a nihilistic fury. Dialogue is short and to the point. The most significant words are those spoken by Hal, and they are far more unnerving than you would ever judge from simply reading the text:

[on Dave’s return to the ship, after HAL has killed the rest of the crew]

HAL: Look Dave, I can see you’re really upset about this. I honestly think you ought to sit down calmly, take a stress pill, and think things over.HAL: I know I’ve made some very poor decisions recently, but I can give you my complete assurance that my work will be back to normal. I’ve still got the greatest enthusiasm and confidence in the mission. And I want to help you.

[HAL’s shutdown]

HAL: I’m afraid. I’m afraid, Dave. Dave, my mind is going. I can feel it. I can feel it. My mind is going. There is no question about it. I can feel it. I can feel it. I can feel it. I’m a… fraid. Good afternoon, gentlemen. I am a HAL 9000 computer. I became operational at the H.A.L. plant in Urbana, Illinois on the 12th of January 1992. My instructor was Mr. Langley, and he taught me to sing a song. If you’d like to hear it I can sing it for you.

Dave Bowman: Yes, I’d like to hear it, HAL. Sing it for me.

HAL: It’s called “Daisy.”

[sings while slowing down]

HAL: Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer do. I’m half crazy all for the love of you. It won’t be a stylish marriage, I can’t afford a carriage. But you’ll look sweet upon the seat of a bicycle built for two.

If you want to go through the cutting edge knowledge of this movie, documentaries like this, this and this example will show you the way Kubrick worked and how his vision was incredibly prophetic, but to appreciate the achievement you have to see it as a whole, much as you can only judge a Shakespeare play in its totality, by stepping backwards so the individual brush strokes are no longer visible.

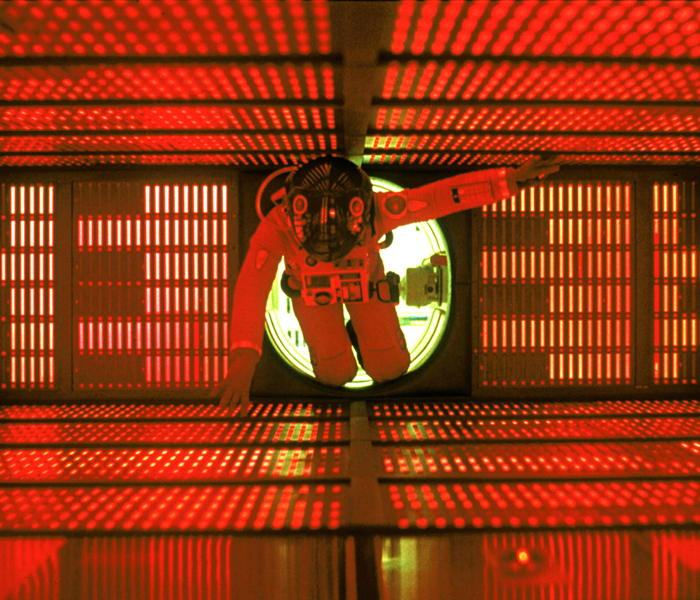

Every shot is composed like a painter might compose a canvas, every sound and note chosen for its impact at the critical moment. The special effects are, for 1968, nothing short of miraculous, but a study in the craft of movie making by a visionary who knew precisely what he wanted. Without Kubrick’s innovation, the likes of Gravity could not have existed. Some of the graceful touches look simple but took technical genius to devise, like the weightless crew member walking around the cylindrical corridor in the space station in order to walk through another door, apparently upside down.

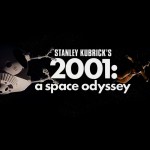

There will be some viewers to whom 2001 makes little sense: what is the purpose of the ape men scenes? What is the significance of the monolith? What is the connection with Jupiter? What on earth do the ending scenes mean, with Keir Dullea (who does a fine job in creating a character with no history but merely follows his mission) having travelled beyond infinity and then getting reborn? The answer is to look beyond the literal and regard these manifestations as metaphors in a bigger philosophical game. The ape men die out but the monolith remains into a point of time and space that men can estimate its significance: we have to look beyond evolution, but the interpretation of meaning is a very personal thing.

As with his other movies, Kubrick retained ambiguity in 2001 and left it to the intelligence of his audience rather than relaying a didactic message telling us, patronisingly, what to think. Would that many other directors credited the audience with cognitive capabilities. Not everyone would be on Kubrick’s wavelength but at least this is work that you can think through for yourself and interpret in a context appropriate to you.

RIP Stanley Kubrick – one of the greats.

PS. This revisit of 2001 makes for fascinating reading.