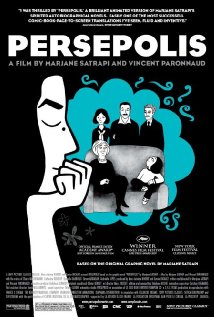

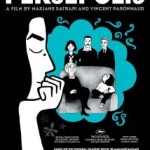

Persepolis was the ancient capital of Persia, and Persepolis is a cartoon autobiography by Marjane Satrani, Iranian artist and writer. A cartoon has to be for kids, right? Wrong. Animations can be so much more, following in the great tradition of graphical stories told in comic book format.

Persepolis is a moving, wryly witty and remarkably perceptive telling of what it was like to grow up in Iran against the backdrop of a momentous period in the history of a nation traumatised over many centuries of conflict. It covers the Iranian revolution, the Iran-Iraq war and its aftermath through the eyes of the young Marjane and her family, and the contrast with western civilisation when Marjane spends a not altogether successful few years in Vienna.

And yes, it’s animated; and here animation works a treat by playing to the strengths of animation. Largely a tale told realistically, it jumps into stylised retellings of history (such as the British role in installing the Shah as a dictator rather than the introduction of a democratic republic), and beautifully realised surrealist interludes – such as the short sequence as Marjane tells of her journey through puberty as if she were a balloon being randomly pumped up, and indeed two versions of her first love affair, one of which sees the lover as a paragon with a shining halo and the other a hideously misanthropic hunchback.

More than this, animation adds subtle touches one step divorced from reality, some invisible to real action and others that could be achieved but would appear forced and unreal. Anyone who has seen Schindler’s List will recall the scene where the little girl wearing a red coat is the only flash of colour in an otherwise monochrome movie. To me that was overplayed and overblown, where in the black-and-white world of Marjane’s Iran, the use of colour when she travels west is much more effective and tells a story in its own right.

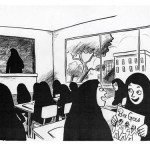

Marjane’s inside knowledge is the key to success, portraying the cultural scism between families coming out of the decadent and corrupt fire of the Shah and into the frying pan of a strict Islamic state from a very personal perspective – what it was like living with the instant shift of culture and with the cream of Iranian youth killed at the front every day, constant police intervention to arrest perceived opponents of the Islamic government, and indeed the punishment of social and cultural transgressions or any notion of identity or independence for women.

Her only permissible form of rebellion is ultimately smoking, which of course is greatly frowned upon in the West. Being at home meant Marjane can take off the head scarf and be like her grandmother, the only person who truly did not give a toss what anyone thought of her. It is the depiction of the views of ordinary people that lend this disarmingly simple story such weight and power.

Doubtless the Iranian regime would be less keen on such an honest revelation, especially when it is set in sharp relief by the wave of propaganda typical of dictatorial regimes, but for the rest of us there is so much to admire in this movie, and I defy anyone to say they dislike what is, in spite of its subject matter, a charming and delightful tale. No, more than that, inspiring and life-affirming.

In fact, what I don’t understand is why the Academy took the bewildering decision to award their Oscar for Best Animated Feature in 2007 to Ratatouille instead – presumably rats were more saleable than honesty and revelations about humanity that year? Or simply that in Hollywood animations are associated with kids? At least it was the co-winner of the Jury prize at the Cannes Film Festival, and rightly so.