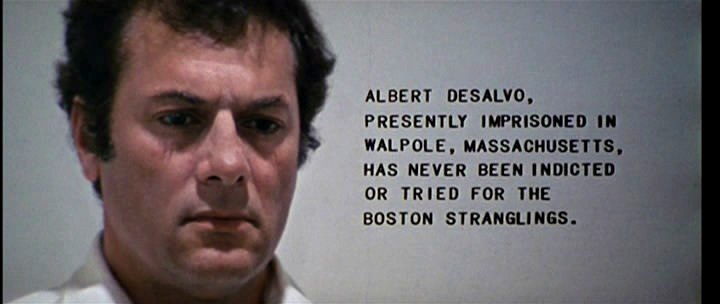

The Boston Strangler is a 1968 movie troubled by two factors, one of which was entirely out of its control: historically it is not a truly accurate depiction of every fact recorded in the book on which it is based, meaning that it is essentially “inspired by” the story of the Massachusetts serial killer infamous for his spree of 13 murders between 1962 and 64, that are known – though it does seek to portray the events as facts. The second factor is the revisionist school of thought that Albert DeSalvo was not in fact the Boston Strangler, or at least not the only one, since the MO changed notably – though the very limited DNA means that we will never know for sure. From Wikipedia:

DeSalvo’s attorney Bailey believed that his client was the killer, describing the case in Defense Never Rests (1995). Susan Kelly, author of the 1996 book The Boston Stranglers, accessed the files of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts “Strangler Bureau”. She argues that the stranglings were the work of several killers rather than a single individual. Another author, former FBI profiler Robert Ressler, said that “You’re putting together so many different patterns [regarding the Boston Strangler murders] that it’s inconceivable behaviorally that all these could fit one individual.”

If you regard the movie as depicting one version of events and ignore discrepancies, what you’re left with is enthralling. Director Richard Fleischer for the most part eschews the voyeuristic, prurient and gory and instead creates a movie of two halves focusing intensely on the minutiae of human psychology:

- The first half is dedicated to the cat-and-mouse hunt for the perpetrator as victims pile up, and the fear invoked among single women of a certain age as the murders put them at risk of being the next victim. Why, the movie asks, did they continue to open their doors to strangers in spite of repeated public warnings, no matter how credible the person might appear?

- When DeSalvo is arrested, a fresh cat-and-mouse game as Henry Fonda’s dogged assistant Attourney-General John S Bottomly, appointed by his boss Edward W Brooke to clear up the crime relentlessly questions Tony Curtis‘s DeSalvo until a confession emerges at the very end of the movie. The two form a double-act, Fonda as the straight man and Curtis, if not the comic then certainly the source of all punch lines.

The first half is at times ponderous and reminiscent of 50s cop shows, interspersed with interventions from weirdos and cranks, plus interrogations of would-be suspects who mostly turn out to be saddos and minor offenders who would happily bathe in the limelight, were it offered. The second, however, becomes increasingly hypnotic, culminating in a compelling confession with camera locked on to DeSalvo.

Let’s be clear about one thing: this is the performance of Curtis’s career. It is a stupendous, magnetic portrayal of a serial killer, regardless of how closely it mirrors DeSalvo. Heis suspected of having schizophrenic tendencies or multiple personality disorder, but whatever is driving him Curtis gets right under the skin in a bravura display of acting, the kind you barely ever thought him capable of delivering. The hairs on the back of my neck stood on end and a tingle went down my spine, that kind of performance!

Yet for some reason unknown the Academy did not even nominate Curtis for Best Actor. In fact, the movie did not warrant a single Oscar nomination. Maybe the words of New York critic Renata Adler were ringing in their collective ears?

“The Boston Strangler represents an incredible collapse of taste, judgment, decency, prose, insight, journalism and movie technique, and yet—through certain prurient options that it does not take—it is not quite the popular exploitation film that one might think. It is as though someone had gone out to do a serious piece of reporting and come up with 4,000 clippings from a sensationalist tabloid. It has no depth, no timing, no facts of any interest and yet, without any hesitation, it uses the name and pretends to report the story of a living man, who was neither convicted nor indicted for the crimes it ascribes to him. Tony Curtis ‘stars’—the program credits word—as what the movie takes to be the Boston strangler.”

I grant you this is a flawed movie, but I’d dispute heavily almost every aspect of that review since the one thing the movie does brilliantly is provide depth, balance and perspective, and, compared to many serial killer movies, its taste is impeccable. What, I wonder, did Adler make of Zodiac, for comparison?

However, the real failure Adler fails to mention in that quote was the use of multiple split-screen effects in many shots, particularly when murders are being discovered. It adds no obvious value and I found the technique to be distracting and unnecessary – much like 3D in fact.

So opinion may have been mixed and the methods not entirely successful, but time has been kind to the movie in one sense – the performances have matured and stand out in their own right, which in many ways is the best you can expect of biopics. If facts are going to be amended for dramatic purposes, I’d much sooner the acting get to grips with the underlying rationale and motivations, which is precisely what Fleischer has done, in the same way that Frost/Nixon did not go for direct impersonations but went for the subconscious thought processes with phenomenal success.