‘In the clearing stands a boxer,

And a fighter by his trade

And he carries the reminders

Of ev’ry glove that laid him down

And cut him till he cried out

In his anger and his shame,

“I am leaving, I am leaving.”

But the fighter still remains’Paul Simon – The Boxer

When this movie came out in 1980 critics lined up to praise it. Retrospectively, many named it the best film of the 80s, and it has repeatedly appeared in an advanced position on lists of the greatest movies of all time. By any standard you choose to measure it, Raging Bull is an extraordinary movie – even by the standards of Scorcese‘s glittering career, a career including the likes of The Wolf of Wall Street, Goodfellas, The King of Comedy, The Departed and Gangs of New York. That it tells the autobiographical story of boxer Jake LaMotta is mainstream enough, but how it tells the story is what differentiates this from a thousand sporting movies and biopics.

The scenes depicting LaMotta being beaten to a pulp are bloody and brutal, wisely portrayed in black and white (home movies are shown in colour), but the real focus is the full panoply of LaMotta’s “self-destructive and obsessive rage, sexual jealousy, and animalistic appetite destroyed his relationship with his wife and family” (Wikipedia.)

The spectrum of raw human moods and emotions make you feel like you have been brawling for 12 rounds with the man who simply would not give up or go down. You name it, he did it – surrounded himself with low-lifes and Mafioso, threw fights, lost his family, lurched from crisis to crisis, but in life just as in the ring LaMotta survived it all.

Bob De Niro is the man who inhabits the skin of LaMotta with such total and absolute conviction he is scary to watch, and I mean terrifying. He lost weight then put on 35lbs to do the later scenes as a bloated LaMotta does a touch of stand-up and arses about in his club to scratch a living, a sad shadow of the man he used to be – and prophetically a starting point for the role De Niro played in King of Comedy. Full credit to Bob, this is acting at its peak – he throws himself into the boxing ring where good men fear to tread with such ferocious intensity you could easily believe he was literally fighting for his life, and for that raw Italian-American passion he won his best actor Oscar by a country mile.

Even La Motta’s domestic life and the wooing with easy charm of the beautiful Vicky (Cathy Moriarty) while still married to the combative Leonora (Theresa Saldana) is done with a verve, a sense of occasion, as if you can feel the inner savage bubbling under the surface with very little prompting. This being the very traditional Italian-American community in the 40s to the 60s, there is inherent misogyny in evidence – women are for fun and kids but business is business. At times the spills over into violence. Even in the good times there is an edge, tension, claustrophobia about relationships, such that trust is never truly a given.

One good example is the relationship between Jake and Joey, LaMotta’s brother and manager played by Joe Pesci, almost the serious twin brother of the psychopathic joker he played in Goodfellas and the man charged with psyching up his man while raging against the injustices of dubious refereeing decisions or playing with women – to the extent that he beats up a Mafia made man. The relationship between the two is complex, for many years one of estrangement after Jake accuses Joey of having slept with his wife.

One telling scene shows Jake asking Joey to hit him, and keep on hitting him, harder and harder, you know this is about Jake proving to the world he is the hardest man out there, prepared to take on all comers and not being afraid to take their best shots in the process. The grudge, the chip on the shoulder is what keeps him going, and that includes family.

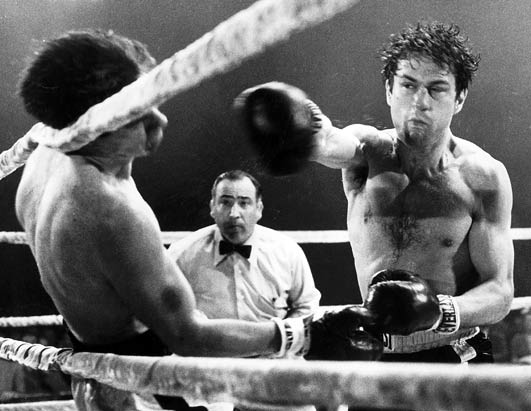

Perhaps it is this feeling that marks the movie apart against others featuring boxing scenes, all of which feel badly choreographed and artificial – which is precisely what they are. Seldom do you see the cut and thrust of boxers going for victory and trying to hurt their opponent, but that is not a criticism you could level at Raging Bull – the pain inflicted in many of these scenes truly made me wince, but for a man whose life and reputation was built around such bloody encounters, you should expect nothing but.

My views on boxing have been well-publicised, but I agree totally with Scorcese’s decision not to pull any punches in showing the full horrors of conflict in the ring, where LaMotta gave the bloodthirsty public exactly what they wanted. You get the shots in slow-mo – sweat flying from crashing blows that break bones, blood gushing forth in an arc from deep cuts, the body shots causing men to bend double in agony, the senseless agony of knock-out punches. But at the end of the brutal sixth and final fight with Sugar Ray Robinson, a bloodied LaMotta calls Robinson to give him more, but then taunts the man for never knocking him down.

Maybe he didn’t escape neurological damage in the process but to a fighter he was doing only what he knew how to do. The sad wreckage of a man that he later became was just part of the same survival process, and he survived long enough to regain fame and a reputation, the sort of comeback that comparatively few make in a lifetime; LaMotta even coached De Niro in the making of the movie. The spirit remains undaunted even to this day – he is still alive in 2014 at 92.

Despite all of this suppressed and real aggression, there is an air of balletic grace to many scenes in Raging Bull, starting with the opening title sequence (to the Intermezzo from Mascagni‘s Caveralleria Rusticana) and continuing throughout the actions sequences. No, it’s more than that: there is a measured beauty in practically every composed shot here, for which praise is due to cinematographer Michael Chapman, the painstaking choice of music and sympathetic scripting add huge weight to the impact of what could have been a simple biopic of a boxer but was declared by Roger Ebert as an “instant classic.”

As I have said about other classics, Raging Bull is a movie to admire rather than to love, so it has my full admiration as a classic in its own right. And as a movie about the inner drive that makes a man survive against all odds and every beating, it’s no accident that Scorcese chose to finish his opus with this biblical quote:

So, for the second time, [the Pharisees] summoned the man who had been blind and said:

“Speak the truth before God. We know this fellow is a sinner.”

“Whether or not he is a sinner, I do not know,” the man replied.

“All I know is this: Once I was blind and now I can see.”

John IX. 24–26, The New English Bible