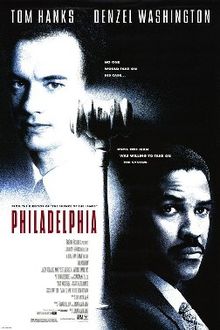

A gay man, Andrew Beckett (Tom Hanks), keeps his sexuality secret, all the better to make progress as a solicitor in a well-heeled Philadelphia law firm. He proves competent and diligent, and is thereby promoted to handle the biggest case in the firm’s history. He becomes ill with AIDS and increasingly finds it difficult to hide the effects of the appalling disease – lesions, weight loss and other symptoms. Paranoia and loathing ensues; the firm makes excuses to take him off the major cases he had been managing, eventually to dismiss him. He takes them to court and eventually wins. He is hospitalised before the verdict but is told he has won the case. Soon after he tells his partner he is ready to die. As the emotional reception is held in Beckett’s honour, so we tiptoe out and the movie ends.

Philadelphia (not to be confused with The Philadelphia Story) is a film that could have been set at any time – even now, given that the abominable practice of homophobia is still rife throughout America and the world, most notably but not exclusively among religious communities – in any city you care to name. It ran into some trouble by choosing this time, place and circumstances and borrowing heavily on the life of a real life solicitor in the same boat. Wikipedia tells the tale:

The events in the film are similar to the events in the lives of attorneys Geoffrey Bowers and Clarence B. Cain. Bowers was an attorney who in 1987 sued the law firm Baker & McKenzie for wrongful dismissal in one of the first AIDS discrimination cases. Cain was an attorney for Hyatt Legal Services who was fired after his employer found out he had AIDS. He sued Hyatt in 1990 and won just before his death Bowers’ family sued the writers and producers. A year after Bowers’s death, producer Scott Rudin interviewed the Bowers family and their lawyers and, according to the family, promised compensation for the use of Bowers’s story as a basis for the film. Family members asserted that 54 scenes in the movie are so similar to events in Bowers’s life that some of them could only have come from their interviews. However, the defence said that Rudin abandoned the project after hiring a writer and did not share any information the family had provided. The lawsuit was settled after five days of testimony. Although terms of the agreement were not released, the defendants did admit that “the film ‘was inspired in part'” by Bowers’s story. Jonathan Demme has stated that he was moved to direct the film after a friend of his, the illustrator Juan Suarez Botas, was diagnosed with AIDS.

Be that as it may, it is a story well worth telling, one that proved inspirational for many to demonstrate the virtues of tolerance. One would hope the subject matter alone did not contribute to the plaudits, Oscars and massive box office that it earned, but aside from the subject matter a straw poll among friends revealed that what people remember most about the movie, fondly and vividly is the impassioned scene where Becket tells the story of an operatic aria, La Mamma Morta sung by Maria Callas from the opera Andrea Chénier by Umberto Giodarno to Denzel Washington‘s Joe Miller, the attorney he chooses to represent him in the case.

If ever one scene could be said to have won an Oscar, this was it. Even people with tin ears and no knowledge or the remotest feeling for the beauty of fine opera came away with tears streaming down their faces, which I take to be a mark of great cinema. Maybe this is just a soaring high in what is otherwise a very competent and well-told tale, but for me it alone overshadows my recent debate on the performance of a lifetime by Hanks (see here), since I don’t believe he ever transcended solid character acting and delivered artistic beauty at any other point in his career quite like these precious moments.

Arguably the scene serves no purpose other than demonstrating the passions deep within Beckett, that he is more than just a lawyer with an illness and a particular sexuality that goes down badly with his employers. Erin Brockovich followed a legal case with a relatively minor dalliance into the private life of its protagonists, and plenty of other court case dramas have managed without even that much delving. But on the strength of seeing Philadelphia you would be hard pressed to say it does not make a towering difference to how you view the character and where your sympathies lie.

Not that you are likely to be cheering for Jason Robards‘ Charles Wheeler, senior partner in the firm and closet homophobe-in-chief, nor his band of acolyte yes-men who seem happy to tell anti-gay jokes. Miller is also a homophobe, but with one key difference: he proves to be a homophobe who learns the error of his ways by correcting the ignorance and prejudice that had held him back. Over time he is accepted by Beckett’s friends and his partner Miguel Álvarez, sympathetically portrayed and even more out of character than Hanks, by Antonio Banderas. If the movie it has an underlying moral it is to tell us that we should always question our own motives and prejudices, and never be afraid to admit we got it wrong.

Credit then to Ron Nyswaner for a script that does justice to the subject, and credit also to Jonathan Demme for attracting a remarkable cast of liberal actors to this movie, adding to the names above the likes of Mary Steenburgen, Joanne Woodward, Bradley Whitford and Charles Napier. I don’t suppose for a moment that their choice to participate in the project is accidental, nor entirely financial; the clear inference is that this is a message that needed to be communicated, and that the vehicle chosen amply demonstrates that while Beckett in person is not without flaws, the prejudice against him is institutional. It is society and each one of in society that needs to question our attitudes.

But then opening the debate is also relevant. I imagine quite a few people who are not homophobic believe Wheeler and co would have been quite justified in saying that given the condition they were giving Beckett time off work, not because of their irrational prejudice or that in their view it constituted a serious health and safety risk to those around him, but merely from concern for the well-being of the employee. The fact that they chose to disguise their motives and hide their unalloyed fear is what did for the firm. One imagines that most of Corporate America has had to face similar challenges since then, and is learning by example.

But the final word has to be on Hanks. I really hope he finds another project that demonstrates the heights to which his acting can soar, for here he most certainly earned his spurs.