“Meritocracy (merit, from Latin mereō “earn” and -cracy, from Ancient Greek κράτος kratos“strength, power”) is a political philosophy which holds that power should be vested in individuals according to “merit“. Advancement in such a system is based on intellectual talent measured through examination and/or demonstrated achievement in the field where it is implemented.”

The best person gets the job, right? Wrong, or not necessarily anyway. Depends whether you want to make it a conspiracy theory, but consider this: does the person elected to be President of the USA get there on merit by virtue of being the best person for the job? Like hell they do! Many are there because they are male, rich and have friends in high places, yes or no?

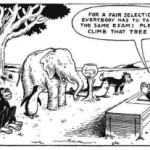

While you’re pondering that question, consider different types of businesses, starting with those that set up the most infinitely complex processes to stamp out favouritism and apply meritocracy in the purest sense. In the UK public sector the rules are strictly enforced to prevent any factor other than the best fit for the role being acceptable criteria, but no matter what rules apply it’s still down to subjective apparaisal and a similar sort of chemistry to that which attracts us to our partners. If you have all the right skills, qualifications and experience but lack the personal magnetism that charms the socks off your interviewers, you will quite possibly lose out to a candidate who may be less well equipped but who talks a better game.

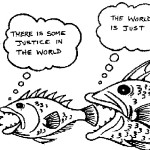

But that doesn’t tell half the story snout why meritocracy, while a wonderful theory, loses out to what you know, what you like, what your prejudices might be, and more. Firstly there’s the most obvious forms of favouritism: nepotism and cronyism, favouring your friends and relatives regardless of ability, while maintaining the veneer of impartiality – or maybe even doing so openly. In short, the contest could be fixed with applicants unaware they stand no chance whatever of getting a job. As the old saying goes: “it’s not what you know, it’s who you know.”

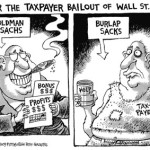

There are other forms of cronyism too, those applicable for people you don’t know directly but who fit the same bracket of establishment such that mutual support can be guaranteed. It used to be the Masonic handshake or the old school tie that created the connection. Those might be less of a factor now but clues on a cv or verbally might tell an interviewer there is a connection. Not conclusive but certainly a big push in the right direction.

Then there is prejudice, since human nature might well dispose even the most equitable of people towards those most like ourselves – which may include race, religion, region (allegedly regional accents are a negative factor for many jobs), gender, age, and (if suspected, since it would not be discussed openly) sexuality. The issue that used to be raised in interviews with women was children: would they be taking a maternity break, would childcare mean they took time off, would they work late etc. Such questions are now forbidden but that doesn’t stop the assumptions and prejudices, nor the glass ceilings that mean 20% of FTSE 100 companies do not have a single female director. Just as racism will not be overt, the fact remains that in many cases a less well qualified white middle class male will be more likely to get jobs in a number of sectors than better qualified women or ethnic minorities – unless tokenism is at play – and all the more so for senior roles.

But there is a difference in some sectors, so take football managers as an example. Male and female games are segregated, but do managers need to be the same gender? Not at all – and in fact a female manager was recently appointed in France. But assuming the gender divide will generally stay in force, it is widely accepted that for the proportion of black players, the number of black managers and directors in the UK is minuscule. Is that because few apply for coaching badges, because they are less able, or because there is institutional racism in the boardrooms of some football clubs? Interesting that most have no problem appointing foreign managers though. Equally we could ask whether managers are appointed on merit, and if so why are so many then sacked at short order? Have they slipped from merit that quickly?

Another relevant factor is that nobody can look into their crystal ball and predict with certainty which character is the most meritorious under any given circumstances. It’s often less about skills, qualifications and experience and more about style for the place an organisation finds itself in. The style of leader required may he radically different. One oft-quoted example is that of Churchill, widely regarded as the best wartime leader in British history but among the worst for peacetime. In a private company a leader who is best for gung-ho capturing of market share is not best for a position where selling assets and closing capacity is the financial imperative – and vice versa. Who is the best and how do you know that? Some companies supplement an exhaustive application and interview process with a battery of psychometric tests, ostensibly to determine who will react best in a range of circumstances, all the better to match person to role and especially organisational culture, since a job and an employer is much like a marriage. I may have every competency required but if I don’t fit in it would be an unhappy experience for both parties. Fact is that mistakes are made all the time, and quite often a rejected candidate would have made a far better fist of the role – but as another saying goes, “you pays your money and you takes your choice” – and that choice may well be quite different depending on who is doing the choosing.

Are there any genuine meritocracies though? Any organisation professing to be such would probably be easy to pick apart, though at the extremes of companies requiring niche skills it is quite possibly true – people are appointed on merit and at whatever cost to get the right creative talents. Why? Because that are ultimately the biggest earners for the company. The problem is that the people with the greatest talent are less likely to be loyal to that company and more likely to be swayed by big deals to poach them by competitors. You can’t run an entire organisation that way so a balance is required, incorporating a number of hard-working loyal staff who know the business backwards and offer the continuity needed to see it through. Their skills are different but every bit as essential as the high flyers. But then any organisation needs a balance of skills, not all of which lead to advancement or greater earning potential.

Society as a whole needs cleaners and carers, some of whom do their jobs with absolute dedication, yet they are never promoted or paid in accordance with their merit. We only do that to people whose skills are deemed to be scarce and in demand. Neither do we do it for the most part in the food, catering and hospitality industry, though to cook good food and provide excellent service can be a rare commodity that stands out.

“Merit” is therefore a concept taken to have a narrow like-for-like definition and to apply to some but never generically. We promote people we like and who do a good job, and sometimes over-promote, but the ruled are not applied consistently to all. Perhaps it is just a utopian pipe-dream, or maybe an aspiration worthy of homage but impractical but for the fact that we want to pick the best available from the limited selection that apply, not because we have an ultimate choice. Good luck!