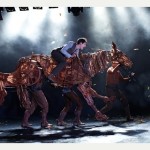

War Horse, the play, is a very different beast to War Horse, the film. Where the latter is Spielberg‘s epic live action hyper-real tear-jerker, the stage adaptation of Michael Morpurgo‘s slim novel is minimal, spare, taut and stylised. Where action is by force of necessity restricted, other means are employed to depict the mood and tone of the scene, notably a jagged screen above the stage, music (without being “a musical” as such), superlative lighting, highly selective props and, of course, puppets for birds, a goose and, memorably, the horses.

As has often been said in many contexts, less can be more. In this case, reducing the clutter helps to focus the action on the key dramatic moments without losing the scale and confusion created by war – so it gives me great delight to report that the stage production is at its best in the second half when portraying the parallel narratives of young soldier Albert and Joey, the horse the trained and with whom he forged an inseparable bond.

The success of the piece depends wholly on the emotional connection between boy and horse, and for that to succeed the audience must believe totally in the puppet creation of Joey. Not the first time such a device has been used to great success, of course: the stage version of Lion King delivered astounding human-driven animals of all shapes and sizes as part of its production design; and it is only a week since I was writing about the puppetry of Audrey II in the Manchester production of Little Shop of Horrors.

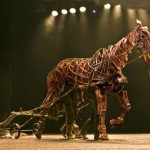

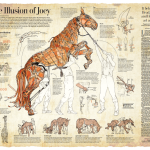

But to create and manipulate horses on stage requires true genius, such that they move like real animals, evoke the feelings and behaviours of the beasts, and, ultimately, allow you to forget the mechanics and think only horses. For this work of genius we should thank the Handspring Puppet Company of South Africa, and for the “horse choreography” Toby Sedgwick, since they have created a design masterpiece, one that could only have been achieved by very many house of studying horse anatomy and psychology, right down to the tail flicks and hoof stamps.

An example: there is a moment in the second half when this deceit works to perfection. The two horses, Joey and Topthorn – initially hostile but eventually friends and allies – stand at the back of the stage in half-light while action is focused on the actors in the foreground. You could forgive the director for allowing them to stand motionless, but in fact they stay in character the whole time with full interaction, nuzzling and all, aided and abetted by their three human puppeteers. If you didn’t know better you would think, in the dim light representing dusk on a French battlefield, those were two real horses, with flesh, blood, moods and emotions.

However much wonder is created by the puppet horses, you should not go away thinking that is the only reason to visit the show. While they may ultimately be the rationale behind the show, they cannot survive without the unfolding drama and horrors – and especially the human resolve for coping against the odds.

That music is often the chosen medium was unexpected but not ineffective. There is a balladeer who comes onstage throughout the play to provide a melancholic commentary, much like a Greek chorus. During the moments of heightened tension, like movies an orchestral soundtrack plays, arguably a means of manipulating our mood but effective nonetheless. The use of song harks back to the days of narrative tradition in song, apt for the Dorset country in which the play is initially set.

In my introduction I also mentioned the lighting within the show, which to my way of thinking deserves at least as many awards as the equine puppetry. It conveys everything from dawn over the farm through to gas attacks in the trenches, almost becoming a character in its own right.

It would be fair to say that many scenes rely on body language and poignant moments like where an English and German soldier flip a coin for Joey after he is rescued from the barbed wire. Knowing the story from the movie, albeit simplified and sharpened for stage, I could easily signpost events, but for the benefit of those who have not seen the film hearing the words becomes all the more vital – and missing the words results in the subtleties of feeling and layers of character study being lost.

Perhaps the weakest aspect of this production was that the dialogue was often not conspicuously audible. Granted my hearing is impaired and we were sitting up in the gods, but my daughter, whose hearing is 20:20, was asking me what was going on at regular intervals. While I know too well that resonance of the voice to fill the space is a primary acting skill, a big old theatre perhaps calls for greater amplification, and would not in my opinion have harmed the dynamics of the show.

In fact the cast does a sterling job with well-defined characters, though forgive me for not having their names to hand – my programme seems to have gone AWOL between Bristol and Essex. Admittedly the work does not require too many complex transitions, so arguably the characters as written never need to extend beyond 2.5D, but nonetheless the play is well played and works at its own level by charming and delighting audiences. Thankfully it avoids Spielberg’s tendency to aim for the big syrupy ending, concentrating on the bittersweet and allowing the characters to allow actions to speak louder than the words and without flowing tears.

In the full context, War Horse is an excellent theatrical accomplishment, one deserving of its considerable renown and many global tours. I hope the War Horse machine stops there though. The last thing it needs is to be adapted to an ice ballet or whatever nonsense befalls other shows, simply to cash in. And if the stage production proves anything it is that simplicity works best – unnecessary extras merely confound and confuse the message. Three cheers for the virtues of theatrical stage production!