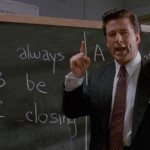

AIDA:

A – Attention I – Interest D – Decision A – Action

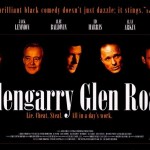

With a delicious sense of irony, the closing titles of the movie adaptation of David Mamet‘s brilliant play Glengarry Glen Ross, a withering depiction of the last vestiges of hope being squeezed from a weary bunch of real estate salesmen, play out to a jaunty version of Irving Berlin‘s Blue Skies, sung by Al Jarreau. No, the skies in the corner of America where this drama is played out are anything but blue.

The ruthless has-beens are given a motivational pep talk by Alec Baldwin’s Blake, one in which it is made amply clear that one will win a Cadillac for being top dog salesman, one might get a set of steak knives and the rest will be fired. How they do it is their own business, but get the business they must or face the consequences.

This is a shark-eat-shark world. Lies and deception are fair game, but unless you close and sell the plots you are nobody. Money in the bank Frank – that’s what counts, nothing else. Blake says he earned nearly $1m last year, and you win no respect by being a good dad to your kids.

The cast applied a nice line in irony by calling this piece “Death of a fucking Salesman” – referencing both Arthur Miller’s great play about the decline of the American dream, told through the life of declining salesman Willy Loman, and excess use of the vernacular in Mamet’s piece – deliberate to the point of irritation.

There is another factor, something even greater currency than cash to the washed-up salesmen. The “closers” – those that get the business – are the ones who get a crack at the prime new leads offered by Blake, the “Glengarrys.” The salesmen grumble to humble office manager John Williamson (the brilliant Kevin Spacey, of whom more anon) about how the old leads are poor quality, but that cuts no ice – bad workman blames tools etc.

The four salesmen have to pick themselves up and sound like winners, though you can hear in their voices that the heart is not in it, which is why they are rejected time and again in spite of the lowdown lies and tricks. They are stuffed full of words; words are all they know, so they spout words 19 to the dozen – though the content of the speeches is less important than the tone. They ooze failure and desperation from every pore.

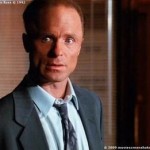

Among their number are two “good guys” are Dave Moss (Ed Harris) and George Aaronow (Alan Arkin), who cook up a plan (or Moss does, Aaronow goes along) to steal the Glengarry’s. When the leads go missing, is it this pair that have broken in and taken the precious papers? Or has one of the other desperate dudes taken them?

Most desperate of all is Shelby “the machine” Levine (Jack Lemmon), a veteran and former salesman of the year, stumbling on a long bad run and whose chronically sick daughter means bills he can’t afford to pay. He lives off the memories of past triumphs, how he sold 8 plots in a day at Glen Ross, but painting himself as the hero is all hearsay and long, long gone. Lemmon won an Oscar for Save the Tiger, but if ever you wanted a demonstration of his ability to act in a straight role and be utterly convincing, this is the one. For all the bravado he is crumpled and looks it, buoyed only by the unwarranted praise of Al Pacino‘s Ricky Roma near the end.

Roma is the current top closer, though even he struggles. He accosts a gullible failure called Lingk (Jonathan Pryce) in a bar and works through his life like a therapist before bringing him back to the office. Instead of landing the catch, Williamson’s intervention allows the fish to escape, which costs Roma his Caddy. He is not happy, as his rant back to the unmoved office manager makes amply clear,

Spacey’s Williamson is unmoved by the insults of the sales force. He has heard it all before, but does not take kindly when he suspects the running of his office has been exploited. Immune to offers of future wealth from guys who will never earn a dime, he is suddenly in a position of power, whether to turn them in and get them sacked or allow them to stay but remain in a position to blackmail the offender.

This ultimately is the theme of the story – power games. Whose games win out I will leave you to guess, but in the final analysis the conclusion is that old school sales guys are a dying breed and have to stick together, in spite of the rivalry imposed by the monthly sales contest. Despite everything there is a sense of community between these men, a reverence for their way of life. To we viewers our hearts bleed for all the punters conned and cheated into deals that will give them something they neither want nor need by men who would sell their grandmothers for half a crown. We know, as the salesmen know, that the deals will lose money hand over fist, but as with Death of a Salesman, the culture of selling represents the American dream and its ability to sell sell sell.

GGR has a superlative cast, one of the finest ever assembled, attracted by the quality of the raw material, and they do a magnificent job with Mamet’s script. This does not mean this is easy viewing. Far from it – there is a repellant, reptilian quality to the characters, imbued by acting of the very highest standard. It failed at the box office not because it failed to deliver but precisely because it did exploit Mamet’s uncompromising message – which uncomfortable message was not the one American audiences wanted to hear.

A pity – though DVD viewers can reap the rewards. Maybe this is not a movie to enjoy, though it works at so many levels that it is a shame not to admire the lessons in psychology and philosophy taught with such spellbinding eloquence, even if at times it looks more like a car crash.