Everything

Everything gives you cancer

Everything

Everything gives you cancer

There’s no cure, there’s no answer

Everything gives you cancerDon’t touch that dial

Don’t try to smile

Just take this pill

It’s in your fileDon’t work hard

Don’t play hard

Don’t plan for the graveyard

Remember –Don’t work by night

Don’t sleep by day

You’ll feel all right

But you will payNo caffeine

No protein

No booze or

Nicotine

Remember –Everything

Everything gives you cancer

Everything

Everything gives you cancer

There’s no cure, there’s no answer

Everything gives you cancerJoe Jackson – Cancer

Cancer is the modern plague, that for which we have no cure but which everybody stands a high chance of acquiring at some point in their lives – at least in part thanks to medical advances that mean we all live longer and are much less likely to die from a spectrum of other diseases that at one time killed people routinely.

We are all touched by this disease – or, since there are over 100 known varieties of cancer, this family of related diseases. There’s not one of us who doesn’t know someone who suffered, was treated for and possibly even died from the common killers, like breast cancer, cervical cancer, bowel cancer, prostate cancer, melanomas and many more (see here for the top 20.) Also, see a range of useful statistics here.

Worst of all is when genetic inheritance or environmental factors cause paediatric cancers, and if anything brings home to us how awful cancers are it is when we see the innocent suffering and sometimes dying from carcinomas. One of my school acquaintances died from leukaemia at the age of about 17, which at the time I merely pushed out of my mind. My bad, but at that age worrying about cancer is the last thing you want.

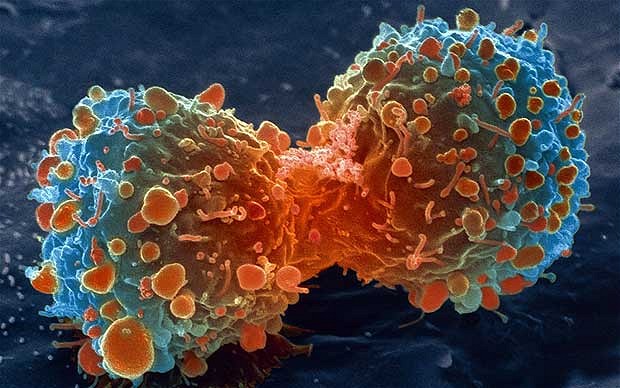

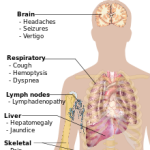

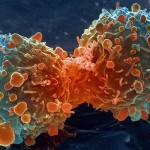

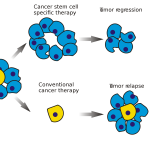

There are over a hundred varieties (see the list here), some of which are very rare and each is distinct and possessed of its own unique characteristics. They are, however, united by the common theme of malignancy – that is, the predisposition of cancerous cells to grow aggressively and not stop, in defiance of the body’s control systems. From Wikipedia:

Malignancy is most familiar as a characterization of cancer. A malignant tumor contrasts with a non-cancerous benign tumor in that a malignancy is not self-limited in its growth, is capable of invading into adjacent tissues, and may be capable of spreading to distant tissues. A benign tumor has none of those properties.

Malignancy in cancers is characterized by anaplasia, invasiveness, and metastasis. Malignant tumors are also characterized by genome instability, so that cancers, as assessed by whole genome sequencing, frequently have between 10,000 and 100,000 mutations in their entire genomes.[2] Cancers usually show tumour heterogeneity, containing multiple subclones.[3][4] They also frequently have reduced expression of DNA repair enzymes due to epigenetic methylation of DNA repair genes or altered microRNAs that control DNA repair gene expression.

The stages of cancer should also be noted, since treatments are always more effective when caught in the early stages:

Number staging systems usually use the TNM system to divide cancers into stages. Most types of cancer have 4 stages, numbered from 1 to 4. Often doctors write the stage down in Roman numerals. So you may see stage 4 written down as stage IV.

- Stage 1 usually means that a cancer is relatively small and contained within the organ it started in.

- Stage 2 usually means the cancer has not started to spread into surrounding tissue but the tumour is larger than in stage 1. Sometimes stage 2 means that cancer cells have spread into lymph nodes close to the tumour. This depends on the particular type of cancer.

- Stage 3 usually means the cancer is larger. It may have started to spread into surrounding tissues and there are cancer cells in the lymph nodes in the area.

- Stage 4 means the cancer has spread from where it started to another body organ. This is also called secondary or metastatic cancer.

Sometimes doctors use the letters A, B or C to further divide the number categories – for example, stage 3B cervical cancer.

It’s fair to say that research into cancers is still in its infancy, though treatments by combinations of chemotherapy, radiotheraphy, surgery and others have resulted in increasingly successful outcomes, particularly when diagnosed early. For my sins I’m currently working on improving cancer pathways with the biggest and most complex Acute provider in the UK, Barts Health, so I know only too well that there is a long way to go in getting the cancer prevention, diagnosis and treatment industry working at its most effective.

In short, for now there is still and will continue to be a strong possibility that the more pervasive cancers will kill, and once other options are exhausted the best clinical care can offer is palliative options to allow you to die a dignified death. The survival rates for some are excellent while others give you little or no chance to escape. Mortality is always on the mind of a cancer patient:

Percentage of patients deceased within five years after diagnosis:

- Pancreatic cancer – 93%

- Liver cancer – 83.9%

- Lung cancer – 83.4%

- Esophageal cancer – 82.7%

- Stomach cancer – 72.3%

- Brain cancer – 66.5%

- Ovarian cancer – 55.8%

- Leukemia – 44%

- Laryngeal cancer – 39.4%

- Oral cancer – 37.8%

- Colon cancer – 35.1%

- Bone cancer – 33.6%

- Colorectal cancer – 33.5%

- Cervical cancer – 32.1%

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 30.7%

- Kidney cancer – 28.2%

- Bladder cancer – 22.1%

- Uterine cancer – 18.5%

- Breast cancer – 10.8%

- Skin cancer – 8.7%

- Thyroid cancer – 2.3%

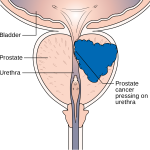

- Prostate cancer – 0.8%

So what causes cancer? OK, so Joe Jackson had his tongue at least partly in his cheek when he wrote those lyrics, even if the theme is serious. Scarcely a week goes by without a scare story about one thing or another causing cancer. Many will be disproven over time though some may prove to be founded. If we were to take all of these seriously, as suggested by Joe Jackson’s song, we would barely have time to live. His underlying message, in sharp contrast to the health lobby, is simple: stop worrying about what the latest research tells you will cause cancer – live like you mean it and don’t stop doing what you enjoy. If you’re going to get cancer you’ll get it regardless, so carpe diem.

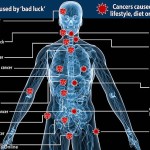

And at least in part, he’s quite right. This blog reminds us of a recent study pinpointing that “rogue cell” cancers are the primary cause of up to two thirds of cases, which still means one third are the result of a combination of human behaviours, including but not restricted to smoking, and unfortunate genetic predisposition:

A recent study announcing that two-thirds of all cancers are just a matter of “bad luck” has made its marketing rounds, with the conclusion that all we can do to deal with our rogue mutated cells is to go to the doctor for early detection and treatment. (Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions, Science 2 January 2015: Vol. 347 no. 6217 pp. 78-81).

While there are undoubtedly rival perspectives suggesting other originating causes, the blogger here goes on to suggest one possible result, imbued with a hint of darkness:

Of course, this is good for the cancer detection and treatment industry. If cancer is out of our control, unrelated to lifestyle and genetics but merely a chance event, then you need repeated and thorough cancer screening throughout your life.

In my case, my dad had prostate cancer so when I reached my early 50s I went to the GP and subsequently for blood tests to check my PSA levels. I’m told I should now have a test for prostate cancer every year, but everywhere you look there is advice for self-checking in case you have any potential tell-tale signs of cancers. We are told to check our breasts and our testicles, look for blood in our urine and our bowel movements, to watch our moles for asymmetry, for women of a certain age to go get an annual cervical smear.

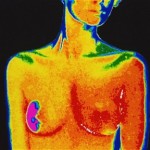

Screening clinics are now commonplace in walk-in centres and polyclinics, allowing PET scans for breast cancer and other indicative diagnostic tools to be applied, but even then the proportion of positive diagnoses is relatively low. An audit of breast screening services in 2010/11 found the following:

2,221,938 women were screened by the UK NHSBSP in England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland between 1 April 2010 and 31 March 2011. 17,838 cancers were detected in women of all ages; 80% were invasive, 19% non-invasive and 1% micro-invasive. The invasive status of 7 cancers was unknown.

In the UK as a whole in 2010/11, the cancer detection rates for all cancers and for small invasive cancers (<15mm in diameter) were 8.0 per 1,000 women screened and 3.3 per 1,000 women screened respectively. Eight screening units have had cancer detection rates for small (<15mm in diameter) cancers below 3.0 per 1,000 women throughout the 3-year period 2008/09-2010/11.

63% of women with a screen-detected breast cancer were aged between 50 and 64 years when they were invited to attend the screening appointment leading to their diagnosis. 26% of screen-detected breast cancers were diagnosed in women aged 65-70 years. 7.3% of cancers were detected in women aged 70 years or more.

In short: the likelihood of cancers being detected does not increase with higher volumes of patients being screened, but in any case screening is merely a shortcut to finding and treating earlier the symptoms of cancers. Curing cancers with a panacea would be nice, but won’t be happening any time soon, particularly since the cure may be very different for each cancer. Until then we have to accept the necessity of pumping our bodies full of toxic chemicals, radiation or undergoing surgical excisions – even if advances are being made in hormone therapy.

My major worry about treatments is that the pharmcos will develop not panaceas – because such things simply don’t exist – but drugs which marginally extend life for sufferers of rare cancers, at a huge cost since the volumes of patients who can benefit may well be tiny and the development costs may be vast.

The question you ask yourself is whether this is the most effective use of the very scarce resources available to spend £10-20k per annum on one treatment for one patient to gain an extra six months of life, if the same money could provide a better quality of life to 100 other patients? The patients and their loved ones will certainly think so, and the average man on the street would say the NHS is there to provide whatever treatment the patient needs, free at the point of delivery.

In the greater scheme of things, resources are not infinite, so it’s down to the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (blessed with the acronym NICE) to make the decisions about what is viable and what is not – and each time they decide against there will be a cohort of patients who say rightly that they have been paying their taxes but in their hour of need the Health Service has let them down. Nonetheless, the line has to be drawn somewhere, and until such time as a definitive cure has been discovered all treatments will offer relative rather than absolute benefits.

However, the greatest trick will be when science tells us definitively how we can prevent cancer entirely, and when people will actually follow the advice. It’s more than 50 years since people learned that smoking causes cancers and other heart and lung diseases, and the prevalence of tobacco is far less pervasive than it was then. Many of our greatest talents died young because of lung cancer, but ask smokers and they will shrug their shoulders. The arguments they raise will include:

- It is a matter of personal freedom to behave how they want

- They enjoy smoking

- Many smokers live to a ripe old age

- Treatments are improving

- Something will kill us anyway so why not smoke.

While this is a form of denial that would be undone were the people concerned to feel the pain and suffering cancers might cause them, we also have to recognise that two out of three people born will suffer cancers at some point, even if they recover and live a full life.

Guess what? Joe Jackson had something to say on this subject:

Jackson has actively campaigned against smoking bans in both the United States and the United Kingdom, publishing a 2005 pamphlet (The Smoking Issue’)’ and a 2007 essay (Smoke, Lies and the Nanny State”), and recording a satirical song (“In 20-0-3”) on the subject.

I don’t agree with Jackson since the world is a much better place without having to inhale the noxious fumes from smokers when we’re out and about, quite apart from the cancer risk from secondary inhalation, not to mention that his attitude is essentially selfish and takes no account of personal social responsibility – but it does prompt the question of how we balance our lives between prevention of the most common illnesses and thinking, what the hell, live for today?

For example, how far do we change our diet, bearing in mind the culture change that resulted in the “healthy eating” explosion when it became clear to us that what we eat has a major and direct correlation to heart disease? Clearly the culture continues to change, but it is not as simple with cancers as saying cut down on fried food and sugars. Cause and effect are less certain, and differ between cancers. The advice is often confusing and difficult to follow.

How about cutting down on the likelihood of skin cancers by spending less time topping up your tan, or at least when you do so use a high factor sun cream (and bear in mind that they lose effectiveness very quickly, so buy a new bottle each year)? A lot of people seem addicted to having tanned skin and are not likely to be put off by the direct relationship with the melanoma risk – at least not yet. Personally I think pale is quite attractive, though there’s no doubt we feel better with the sun on our skins.

In the meantime we have to accept the risk, and at least cancers are not the taboo subject they once were. If blokes are even going to get checked for prostate cancers, the world has changed to some degree. But it will be some time yet before we find ways to put cancers in their place, and until then getting tested and treated is all we can do.

Sad to say that at work I hear of cases to this day where people choose to ignore their symptoms out of fear, and eventually are goaded by family in going to their doctor with stage 3 or even 4 cancers, by which time it may well be too late to do anything. That is the attitude that has to change.

I might also like to state that most of those that find themselves with no health insurance are generally students, self-employed and those that are without a job. More than half in the uninsured are really under the age of Thirty five. They do not feel they are wanting health insurance since they’re young as well as healthy. Its income is frequently spent on housing, food, and also entertainment. Most people that do go to work either 100 or part time are not given insurance through their jobs so they get along without as a result of rising valuation on health insurance in the usa. Thanks for the ideas you talk about through this website.