Someone reminded me recently that I had written about all manner of foods and drinks, but omitted wines. How remiss is that? What on earth was I thinking about?

Clearly it’s time to put the record straight, all the more so since my relationship with the fruit of the vine goes back a very long way. In the French tradition, in fact, where parents give their children watered-down wine with family dinners from a very early age, so my dad used to give me a glass of wine with Sunday lunch from the age of about 11. Trouble was, he was self-avowedly not an expert on wine and detested the snobbery and pretension that often surrounds wine. The wines he bought were not great, it has to be said, but they did give me a taste and everything snowballed from there.

I took this to further levels during my French A-level, for which a dissertation was required. Not unnaturally I chose French viticulture and set about doing my research at Wilmslow library, with help from my mother who worked there as a librarian. As part of my research, my dad took me to visit a company somewhere out in Cheshire that imported wines, mostly from France, then packaged and distributed them for the English market. I was given a tour and a talk, then got to try samples, which for a 17-year old was a total blast!

That research gave me at least a semblance of understanding of the complexities involved in growing vines, interpreting the climate, maturing the fruit to ripeness until it has the perfect sugar content, harvesting, extracting juice and tannins from the skin, fermenting the sugars to make alcohol, ageing the wine and savouring the many qualities to be found within.

The appeal was simple: yes, there are new age winemaking processes that mechanise and automate the process, but essentially the traditions of the vine are very manual, human, artisan skills, depending greatly on the forces of nature. Maybe there is science in the process, but there is also a fine art that is not acquired by all. It is not something that can be picked up by just any propriétaire with money but no background in wine culture – not that there is anything wrong with innovation.

Having learned what to look for I began to acquire a palate and the ability to recognise the characteristics of each grape variety and the virtues associated with maturation, the difference between good and average vintages, how to care for wines to get the very best from them, how to pair them with food and how to enjoy each to the full.

Best of all, I learned that wine is an uniquely versatile beverage. Tell the truth, there are qualities to appreciate in most wines, but it was only as I began to sample better quality and more mature vintages that I learned to appreciate the depth and subtlety of these wines. Not for quaffing but to be savoured and the full flavour extracted.

To this end I began to try wines from different countries and to pick up which characteristics most appealed to me. Perhaps not surprisingly, my favourites were and are big red wines, many from France and Italy but also South African native-born Pinotage and South American Malbecs. Many of the tastes I acquired are quite expensive, not least excellent Barolo and Brunello di Montalcino from Italy, Hermitage and Chateauneuf-du-Pape and Nuits St Georges, to name but a few. The only wines I’m really averse to tend to be cheap, poorly made and to have a harsh metallic taste that jars in your throat and certainly doesn’t make for pleasurable drinking.

As with food, I am not a fan of industrial commoditisation of products that should be made by hand in small batches, and there’s no doubt that with wine the greatest wines with the finest vintages depend on the time-honed skills and expertise of the wine maker. The joy of this art form means there is always something new to learn, and you can never cease to be surprised by the characteristics of what is in the bottle – they vary entirely with the grape variety, the soil conditions, the climate, the weather, the picking and juice extraction, the winemaking process and maturation. Two neighbouring plots could produce radically different wines, and therein lies the joy of vino.

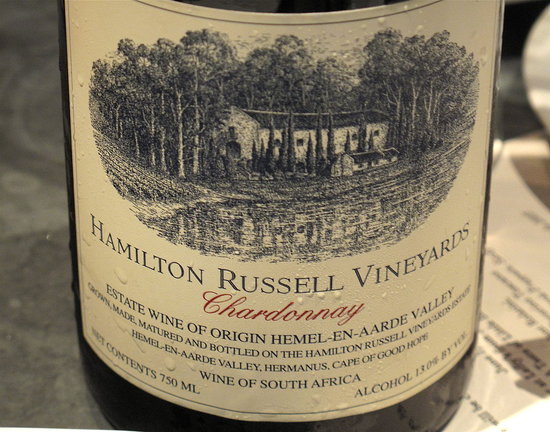

I got a first hand glimpse into the art of wine making when visiting the Western Cape as part of my MBA course in 2001. Straight off a plane at 6am we were taken from Cape Town to Hermanus to see the whales, thence to the wonderful Hamilton-Russell vineyard nearby. HR has since expanded but at the time they produced two brands: Hamilton-Russell chardonnay and Southern Right (after the whales), a Semillon-Sauvignon Blanc made with more modern techniques and pitched at a lower market price point.

The chardonnay was and is made to a very traditional and exacting standards, including an extended period of maturing in top quality oak barrels, which were stacked high and monitored very closely by the winemaker. As with before we were given a tour and a talk, and sampled several great vintages – but most of my colleagues chose not to avail themselves of the spitoon offered! Tasting the product was a revelation compared to the very many inferior chardonnays on the market, such that I was not surprised to learn that bottles typically fetch £20-25 a time in the UK, reflective of the cost of manufacture but also the relatively small quantities produced.

Someday I fancy taking this further with a road trip, akin to the tour of Santa Barbara wine growing areas portrayed in the excellent film Sideways, which did the American pinot noir industry no harm at all. From Wikipedia:

Throughout the film, Miles speaks fondly of the red wine varietal Pinot noir, while denigrating Merlot. Following the film’s U.S. release in October 2004, Merlot sales dropped 2% while Pinot noir sales increased 16% in the Western United States. A similar trend occurred in British wine outlets. Other reports also claimed anecdotally that sales of Merlot dropped after the film’s release. A 2009 study by Sonoma State University found that Sideways slowed the growth in Merlot sales volume and caused its price to fall, but the film’s main effect on the wine industry was a rise in the sales volume and price of Pinot noir, and in overall wine consumption.

The quality and variety of wines on our shelves demonstrates that Brits are educating their palates and becoming far more discerning, resulting in a reduction in the amount of rubbish to be found and marketing based on accepted industry price points. For example, check out the wines now supplied by Tesco and you will see them carefully stratified and searchable by wine type, country (though not region), grape variety, price point, awards won, offers and promotions, and more besides.

Wines are branded with care, some excluding even basic information about the provenance of the wine, presumably on the grounds that some consumers would sooner identify with the branding and trust that than believe their own palates, but in general the British wine buyer will nowadays sample with care and buy based on the characteristics that appeal. Arguably this accounts for the popularity of New World wines in recent years, which as a breed tend to be bigger, more user-friendly and better bang per buck, though traditional wine-growing nations are fast catching up with the newer styles.

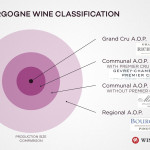

A new breed of young winemakers sprang up in the New World – California, Australia, South Africa, Chile, Argentina, Bulgaria and a host more countries, some of them distinctly unlikely, started producing excellent wines with different characteristics, typically bigger and less subtle than those honed by tradition. They even started to find their way back into Italy and France, where their products were not made in accordance with the rules of appellation d’origine contrôlée and are classified as vins de pays, traditionally the designation for cheaper quaffing wines but now home to some spectacularly good drinking.

So much choice and far better flavours, all reasonably affordable (though still much cheaper to go on a booze cruise to France and bring back your Montrachet and Gevrey-Chambertin from the cash and carries there) and most of them available for the British market. On which note I shall wish you happy drinking and maybe see you all over a bottle sometime!