Love of good food is always rooted in your childhood, or so my grandmother told me – Oma, as she preferred to be called. When I was small she often told me stories of going out with her grandfather to Café Sperl and Café Central in pre-war Vienna and being rewarded with slices of the most amazingly elaborate pastries and cream cakes with a flavour to die for. Even her thick Austrian accent could not disguise the ecstatic memory of being a five-year old and being taken out by the old man, of luxuriating in the warm and magical atmosphere.

She remembered every detail of him, from his heavy woollen check suit and camel overcoat, his smart felt hat with a wide band, his soft kid leather gloves, his tiny round horn-rimmed spectacles, his lush grey beard and the anxious way he would constantly look over his shoulder, as if someone were following him. But even he managed to relax over coffee and cake in the bustling cafés. He took great delight in the old-fashioned service, giving very precise instructions to the waiters, who would note his every whim and would later be rewarded with a good tip.

But it was her description of the cream cakes and coffee that made me certain I wanted to work with food – but not merely for the indulgence of a few well-dressed and affluent clients. The lightness of the sponge, the beautifully set fruit, the wafer thin slivers of chocolate, wave after wave of that gloriously indulgent confectioner’s cream. Oh, and the strudels – crisp and flaky pastry, the moist and spicy apple…. everything set my tongue a-quivering to taste those decadent luxuries in a sealed moment of history, not long before the horrors of war beset the city and the glories of perfect patisserie were reserved for senior officers – and somehow the love that went into the cakes and pastries faded.

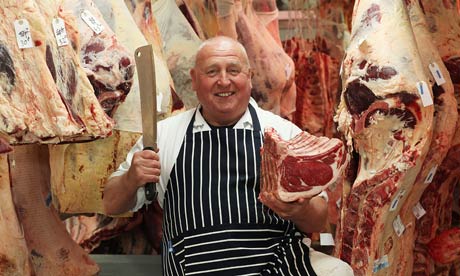

It didn’t take me long to realise that food came in many other wonderful forms, such that I could revel in the flavours my preoccupied parents simply did not appreciate. From an early age I begged them to take me to see the meat and game hanging at the best butchers, to drool over the cheeses at the French delicatessen, hot bread arriving from the oven at the craft bakers, the whole salmons and lobsters displayed at the fishmongers – it was a vivid world in which ingredients were treated with respect and humble artisan skills gained through years of practice were honed and enacted, day in day out.

I yearned for dinners at grand restaurants, but all I got was Wimpy bars and chip shops. I promised myself that some day I would work like a dog to cook and serve the best food possible, and to serve it to as many young people as possible so that they might all be enthused by the magical experience.

So that’s what I did. Like many before me, I left school at 16 in spite of fervent objections from my parents, and made for London, where for a time I slept on sofas of anyone who would befriend me. I spent my days hanging around the kitchens of the great French restaurants of the day, begging for work as a porter. I didn’t give in, so eventually they employed me, if only to keep me quiet. To celebrate I rented the smallest bedsit in town and got drunk – possibly the last time for many years.

Over months and years I learned my trade. After starting right at the bottom, I moved through the ranks of porter and steward, then gradually entered the kitchen hierarchy, starting as the lowest commis chef, the one who took all the blame. I soaked up the knowledge like blotting paper. I chopped onions until my hands were bleeding, I took orders and took on sufferance the rants of the Chef de Cuisine (the maestro would rarely dain to speak directly to the likes of me) – but always learned the lessons from my mistakes. I served my time at all the stations, even for a time as a pâtissier, in which I remembered fondly the words of my grandmother and the joy a perfectly executed pastry might bring.

To rise up the ranks I had to dedicate myself totally and to sacrifice everything else in life – including the urge to find a partner and settle down. Cooking was everything, literally all I had in life. I was so totally obsessed that I never stopped: start at 5 to go to the markets, prep the veg and fish, do the lunch serving, clear up and clean everything, prep dinner, work through to the early hours, grab a greasy spoon breakfast and collapse for a couple of hours sleep before it all began again.

Even when the kitchen stopped go to even in the brief respite between servings, I was there – talking to the sous chefs, honing my techniques, reading books, perfecting recipes. The executive chef knew I was there but turned a blind eye, because that was exactly what he did at the same age. My obsession with food was the same obsession that motivated the top brass to reach the dizzy heights.

Had we cared about money we would have become traders in an investment bank, but we chefs care about ingredients with the passion others devote to financial wizardry. For us, the alchemy that turned ingredients into a perfect dish served before an unappreciative paying customer was every bit as incredible as turning base metal into gold. I doubt if customers ever realised the craft and guile that went into any dish before them, not to mention the sweat, burns, cuts and sleepless nights of the men and women who laboured on their behalf.

It took time but I got noticed and was eventually elevated to the position of sous chef, at which point I ditched bedsitland and rented a one-bed flat close by the restaurant. At least it had a proper kitchenette so I could continue to experiment even when I was dragged reluctantly from my station at the restaurant kitchen, the altar where I would worship each day.

Up to this point my ambition had simply been directed at the food, at the need for total perfection of my art, to the point where I could make any number of dishes on order, presented with exquisite attention to detail, and reject plates that simply did not come up to the mark, but on the day of my promotion my colleagues took me to an all-night bar after serving. Amid the jollity I sipped a beer and wondered for the first time what was next; where would I take my accumulated skills, what would I do with the expertise I had acquired through long and patient practice?

The logical answer was to do what most sous chefs wanted: either to climb the tree and become their own man, the top chef, maybe even a TV chef, open restaurants with my own name, become a legend… The TV chef idea did not appeal one jot – who wants to be a performing sealion? – but there was not a single one of my colleagues who did not dream of having a place where critics and diners flocked by their thousand to sample the signature dish of a great chef.

Many simply could not cut the mustard. Some succumbed to alcoholism and cynicism long before they got there, and several more went bankrupt when the cost of running their own little place to the exacting standards of the great chefs was not matched by the income earned from Joe Public. Some eventually found other jobs, easier jobs along the way and settled for what they could – with at least a touch of control of their working conditions, a regular wage and family life.

The worst, the ones who were never going to make the grade, earned the disapprobation of their former colleagues by taking up catering – buying in convenience dishes by the thousand, to be microwaved and served to customers who could not appreciate the difference. We all despised them for selling out, but we all had to make a living. Was I going to be any different?

While pondering this dilemma, I took a rare weekend off and went to see my Oma. She was well into her 80s, living in a sheltered home and occupying a wheelchair by this time, but still sharp as the blade I would use to fillet a dover sole. She knew of my career, and of how her stories had inspired me, but it had been some time since I had seen her. In the ensuing time her skin had taken on the pallor and wrinkled complexion of old age, but her eyes burned as bright as ever.

“You are a lieber Bub,” she said as I came bearing a box of Buchteln sweet buns I had made specially, “Ahhh yes, my mother baked these when I was so high. Give me a kiss.”

And so I kissed her forehead and sat down to regard this formidable woman.

“Nobody comes to see me nowadays,” she continued, “though I know you are a fleißiger Arbiter. Ich verstehe.”

“I’m sorry, I don’t speak German,” I smiled back, “but I have learned a lot of French from working in restaurants.”

“Let me look at you. Those clothes – you look like a scarecrow! But you are not married… you need to find a girl to take care of you, let the others work for you for a change!”

“That was one reason I needed to talk with you, Oma. I am thinking ahead, wondering what to do when I have reached the top. Maybe I will be working another five years in those kitchens before I get there…and maybe someday I will find time to get married”

“Good boy, I know you will…for me.”

“Yes, for you, because I owe all this to you. I had an idea…”

She looked me squarely in the eyes so I knew I had to continue. “I wondered whether I should aim to get some rich backers and open a Viennese coffee shop like the ones you told me about. Then I could serve patisserie, and maybe Gulasch, Wiener Schnitzel, and Schäufele und Knödel – everything you remember from when you were a girl. How does that sound?

If I had expected a look of wistful delight to break out on her expressive features, that hope was soon shattered. Oma certainly had a tear in her eye, but a frown on her face. Whatever memory had been served up by my vision was clearly not a happy one.

My concern was evidently etched upon my features, for she waved her hand and produced a beaming smile from thin air. “Ach, so long ago.”

“No, do tell me. What did I remind you of?”

“Schäufele und Knödel mit Sauerkraut,” she repeated slowly. “The pork. That was how they knew.”

“Sorry, Oma, how who knew what?”

“You see, meine Mutter married a Catholic man – which nearly caused the break-up of my whole family. But anyway, I was raised in that faith in spite of the fact that she was brought up as a Jew. I went to the cafés in the 1930s with my Opa, who was a Jewish man.

“He knew the times were changing and anti-Semitism was on the rise, particularly when Hitler came to power in Germany and he knew the Anschluss was only a matter of time, and our own Austrian Fascist regime under Dollfuss could not last. There were lots of sympathisers who aligned with the Nazis and very many anti-Semites, not just the mob either – some were senior people, sophisticates, cultured people who knew the score and wanted to be on the winning side.

“They were the sort of people you would see in the cafés. They were well-dressed, charming people – but dangerous, and my Opa knew that. There was one occasion we were in the Café Central, when one of these men came up and introduced himself. His name was Viktor Ebner, and he asked if he could join us. He was wearing a very smart suit and tie but he wore it with ease, as you would expect of someone brought up in the aristocracy. He had a charming smile too, though I could tell my Opa was frightened of him.

“Herr Ebner took out a gold cigarette case and offered Opa a cigarette, which he refused. They were Turkish, I think. Herr Ebner lit his cigarette and looked at me for a long time while he dragged on his smoke. He blew out a ring and said to my Opa in a friendly way, ‘You have a most delightful granddaughter, Herr….’ ‘Schuster,’ said my Opa. This puzzled me because it was my father’s name, not his name. His name was Goldberg, not that I understood the significance.

“The man continued talking, ‘Well you should be proud of your granddaughter, Herr Schuster. Alas, my only grandson died recently of a terrible illness. It is a great tragedy when our children die young, is it not?’ So my Opa nodded and sipped his coffee. The man went on talking, then as the waiter passed by he spoke briefly. The waiter nodded and went off. This is what Opa would have done normally.

“‘I hope you will not mind but I have ordered us some champagne and a special drink for the Kind. What is your name, pretty one?’ So I told him, ‘My name is Maria-Theresa, mein Herr.’ ‘Ah,’ he said, ‘after our great Hapsburg Empress? You could not get more Austrian than that! So then, we shall drink to your health. I have ordered you a peach nectar. I hope you enjoy?’ And of course I nodded – that was my favourite drink, as if he knew already.

“‘So, how can I help you, Herr Ebner?’ asked my Opa politely. The man pulled on his cigarette again and looked closely at my Opa. ‘Well, sir,’ he said, ‘as you know we are going through difficult and challenging times – it is just good to know that old Austrian families are continuing our way of life. And what could be more Austrian than to eat in our grand cafés? In fact, let me buy you lunch. I insist!’ And he waved away my Opa’s objections, like that.

“He picked up a menu and said to us, ‘And the most Austrian dish of all is surely Schäufele und Knödel mit Sauerkraut. The waiter had just returned with the champagne and the fruit juice for me, so he loudly, ‘Bring us your finest Schäufele, enough for three please.’

“Now at that age I was naive. I did not know the religious issues. We were not a strictly observant family, and being Catholic we did eat pork, often. I loved charcuterie and sausages and bacon, and I adored Schäufele and especially the rich and gooey yet incredibly light dumplings, so obviously I clapped my hands in delight when he said this. I did not know any different at my young age.

“But when I looked up at my Opa I knew something was wrong. His face was grim and tight-lipped. With a tiny movement he looked at me and shook his head, so slight I could barely see him – but the look in his eyes warned me off. I knew instantly something was wrong – and Herr Ebner could read this from our reactions.

“‘Sir,’ said Opa, ‘You are most kind, but I must reluctantly decline your offer. I must return young Maria-Theresa back to her mother or I will be in deep trouble haha.’ Her Ebner smiled, then opened his mouth and roared with laughter too. I could not help but giggle, though I was not really sure what the joke was.

“But then he stopped laughing abruptly. He said to Opa, ‘I’m afraid that I’ve ordered the food now, and it would be very rude for you to refuse. Please – let us celebrate our wonderful country together.’ And with that he took the glasses of champagne the waiter had poured and pressed one into Opa’s hands. ‘A toast!’ So my Opa raised his glass and said, ‘Prost!’ ‘No, no, no,’ said Her Ebner, ‘We must do this properly: to the Fatherland! Neues Leben!’

“Now this was the slogan of our Chancellor, Dollfuss, so we knew this man was a fascist – though that was very popular, very fashionable at the time in Vienna. But Opa did not, could not know whether Ebner was a Nazi at heart, a hater of Jews. By this time I was feeling very nervous for him too. He raised his glass to this toast and drank, but his heart was not in it.

“The conversation continued, but the longer it went on the more uncomfortable I felt. It was obvious we could not leave, and the effect of doing so would be unpredictable – but neither did we know where this very polite but frosty dinner was taking us. It was not me at risk, but I was not going anywhere without Opa.

“And then the food arrived. The waiter made a great show of carving a beautiful big knuckle of pork so I could have a small, child’s portion, with a lovely dumpling on the side and a spoonful of sauerkraut. I was well brought up, so I said ‘Thank you’ – my mother had taught me that good manners cost nothing.

“The waiter then put a pork shank and dumplings in front of Ebner and my Opa. ‘Ah wonderful, does that not look perfect? Guten Appetit!’ said Ebner, winking at me.

“My Opa smiled weakly and picked up his knife and fork. He was not an Orthodox Jew but I later found out that he was observant. He had never eaten pork in his life, but now he had no choice. He ate some of the dumpling, then some sauerkraut. Then he looked up and realised that Ebner was regarding him closely. ‘Do try the pork,’ he said, ‘it’s delicious! Mmmmm I don’t believe I’ve ever eaten better!’

“It was as if those words strengthened Opa’s resolve. He cut a small chunk of pork, coated it in gravy, then brought it slowly to his mouth. While the other man watched, he took the meat into his mouth, then chewed it solemnly, his eyes fixed on Ebner’s.

“But when I looked up it was as if he had become bored with my Opa and was eating his food quickly. ‘There, that wasn’t so bad, was it? Do eat up!’ Whatever dilemma was running through Opa’s mind, he reached a decision at that moment. He put down his knife and fork quietly and replied, ‘I’m terribly sorry, Herr Ebner, but I have quite lost my appetite. Would you mind awfully if my granddaughter and I excused ourselves now?’

“Ebner nodded and grinned back at us. ‘I’ll tell you what,’ he said, ‘My driver is just outside. I have a Gräf & Stift limousine, the finest and most luxurious made in Austria. Why don’t you tell me where to take your beautiful granddaughter and my driver will take her home to her mother. Then perhaps you might be free to join me for cigars and brandy in the back room?’

“Something very strange was happening, but at my young age I could not work it out. Opa was not his normal self. He looked hard at Herr Ebner, swallowed heavily, then turned to me. He patted my head, but I was aware that his mind was elsewhere. ‘Now be a good girl, Maria. Go to the cloakroom and get your coat, then you can have a ride in Herr Ebner’s car. Won’t that be a thrill to tell your mother and father about?’

“And so I did as he told me. I got my coat and said my goodbyes. I curtseyed politely and thanked Herr Ebner. Then I gave Opa a kiss and followed the waiter out. The doorman escorted me to the car, held the door open for me and even bowed as I departed. Let me tell you, I was in heaven! This was an amazing experience for a young girl, I had never known the like.

“So I got home and said hello to my mother. ‘You’re late,’ she said, ‘And where is your Opa?’ So I told her the story. As I did I could see tears welling up in her eyes. ‘Go to your room!’ she said when I had finished. I did not understand what I had done wrong, but she was very worried. I did as I was told, and later I could hear raised voices when Vati arrived home.

“But nobody ever explained what happened in the café – all I knew was that Opa never again invited me for cakes at the Café Central. When I asked they told me, ‘he’s too poorly, he can’t take you today, sweetness,’ or some other excuse. And it was not too much longer before they told me that Opa had died. I never knew the circumstances, but I did know that I never saw my lovely Opa ever again.”

By the time she had finished, my eyes were awash. I talked some more with Oma, but she was tired. The nurse asked if I could let her rest, so I did. I made a point of visiting Oma two or three times more, but it turns out her health was failing too. She died just a couple of months after that meeting, a very long while before I was ever ready to open my restaurant; but, thanks to my feisty grandmother, the decision was taken from that moment she told me the story.

Some years later ‘Café Oma’ opened in a fashionable part of London. It is the finest pâtissier in town, but also offers a range of Austrian specialties. The signature dish, for which people will happily book months in advance, is Schäufele und Knödel mit Sauerkraut.