Amy is a documentary telling of a life story saturated in classical tragedy, by which I mean there is a grim inevitability to the early death by heart failure brought on by alcohol poisoning of a North London Jewish girl with the once-in-a-generation voice who struggled to handle fame – a very familiar story in the annals of popular music. The reasons Amy Winehouse ended up as a member of the notorious 27 club, thereby sealing her legacy as an iconic performer, are suggested throughout this film, though not everyone agrees – of which more anon.

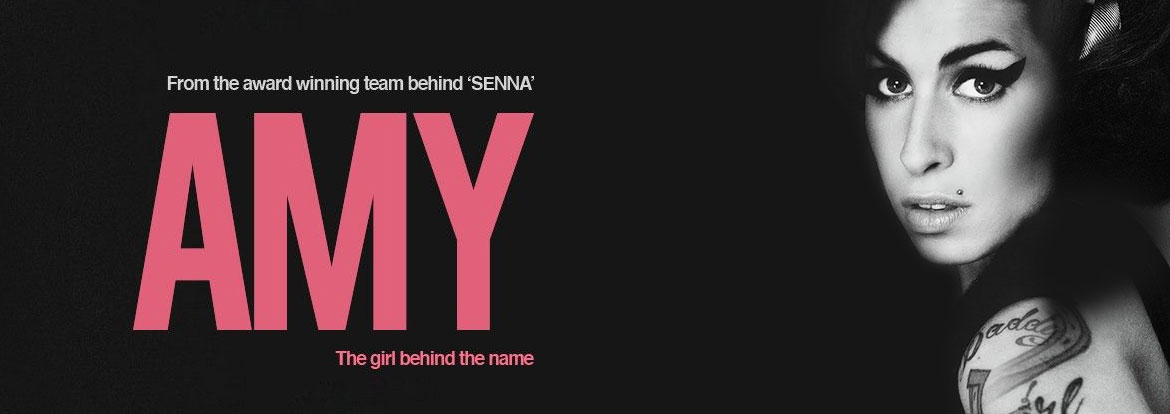

Amy the film constructs a narrative from many hours of archive footage, much of it retrieved from the family vaults. The Winehouse family initially co-operated with director Asif Kapadia and his team, also responsible for the hit documentary Senna, but withdrew when it became clear that Mitch Winehouse in particular came out badly.

In fact, very few people in Amy’s life come out this film smelling of roses, with the possible exception of her childhood friends Juliette and Lauren, and latterly her bodyguard. Too many people had too much to gain from the trials and tribulations of Amy’s life, and many of them led her astray. Had there been more people in Amy’s life she could depend on to keep her on the straight and narrow, the tragedy may even have been avoided.

The film opens with footage of a 14-year old Amy larking about with her friends. Nothing remarkable you might think, but then young Amy sings Happy Birthday to Lauren. It is a magical moment, one that sends shivers down your spine – but then, the raw talent in Amy screams out.

She needed someone to take care of her and keep out the sharks, but the reality was different. Bulimic and depressive from an early age, neither parent seemed able to control her rebellious nature and provide her with the authority and structure she needed. Indeed, she was allowed to do her own thing, say what she wanted, go out drinking with her friends from an early age, not only sexually active but involved with much older men, even move out into a flat of her own. The first older boyfriend eventually got withering contempt for his pains in Stronger Than Me, with lyrics comparing him to a ladyboy (see below.)

While her career took off in parallel, her choice of company inevitably became more dangerous, especially Blake Fielder-Civil, the man who later became her husband and introduced her to heroin and crack cocaine (which accusation he rejects – see here.) Whatever Fielder says, Winehouse’s addictive personality latched on to him, to booze and to drugs, with fatal long-term consequences – not to mention the tattoos that symbolise her transition from an innocent young talent to a world-weary performer in the blink of an eye.

Her father initially denied she needed rehab, though ironically it was dark times including this period that inspired her to write the hugely personal but fiercely brilliant songs that comprise her two albums, Frank (gloriously updated cocktail jazz and a superb demonstration of Tony Bennett‘s quote in the film that she was a natural jazz singer) and Motown inspired Back To Black.

Maybe without the dark side she could never have written the great songs that made her name, though sadly the spells she did have in rehab were followed by relapses before a third album could appear, though there is no doubt at all that post-Fielder and in spite of singing with her idol, Bennett, and winning a Grammy award, she was vulnerable and in greater need of protection than ever – as witnessed by her failure to perform in a contractually obligated performance in Belgrade, where nobody around her could see she was in no fit state to go out on stage, arguably the story of her life.

Nowhere is this more evident than the episode when, in 2009, Winehouse and her entourage spent six months in St Lucia to recuperate from her divorce and drug habit. She needed her father to provide guidance and be there for her, but instead he turned up with a camera crew filming a documentary about him.

Mitch Winehouse may feel that Kapadia deliberately manipulated the footage to make him look bad, but he has plenty of reason to feel guilty for manipulating the daughter who worshipped him at the time when she needed him most. After all, Amy’s parents inherited her estate and the rights to her back catalogue, worth many millions. Speaking as a father who cares about the well being of my children more than anything, Mitch’s actions come across as distasteful and unsupportive.

Doubtless he is busy making an alternative film putting himself in a good light, though Kapadia steadfastly maintains his view was objective and driven by the evidence. Without seeing the full footage it’s impossible to know whether any spin was cast in developing the narrative, but there is no question at all that the film as distributed is powerful, moving and at times shocking, especially to see such a talented performer wasted on drugs squandering her talent. The interviews – mostly on voiceover rather than on camera – are heartfelt, and very few self-serving – though where they are you can easily draw your own conclusions.

Amy did not want to die, but neither could she cope with the constant pressure to write hits and be a public face – and it takes a very strong will to deal with constant intrusion when all you want is to crawl away into a hole and be on your own. Towards the end, the paparazzi were ever present and catching her at her very worst moments, the price of fame. It was her friends who were there for her, so it is all the more poignant that one of her very last acts was to call her friend Juliette to apologies, repeatedly. Amy was very aware she had screwed up the things that matter and needed to repair the damage. Alas, too late for her heart.

This film, for all the questions of its objectivity, is a fine study to portray a 360-degree view of its subject, public and private. With thousands of hours of footage to draw from, it could easily have become a hagiography or a viperish attack on Winehouse.

At face value it seems to have retained a sensitive and thoughtfully rounded view, using evidence to back its assertions and not glossing over or leaping too fast from one facet of a life to another. Not perfect, but Kapadia deserves credit for presenting the tragedy of Amy Winehouse in an accessible and emotionally charged format.

PS. If you are not familiar with Amy’s work or doubt her vast unfulfilled potential, try these examples:

You should be stronger than me

You’ve been here 7 years longer than me

Don’t you know you supposed to be the man,

Not pale in comparison to who you think I am,You always wanna talk it through – I don’t care!

I always have to comfort you when I’m there

But that’s what I need you to do – stroke my hair!

‘Cause I’ve forgotten all of young love’s joy,

Feel like a lady, and you my lady boy,You should be stronger than me,

But instead you’re longer than frozen turkey,

Why’d you always put me in control?

All I need is for my man to live up to his role,

Always wanna talk it through – I’m ok,

Always have to comfort you every day,

But that’s what I need you to do – are you gay?‘Cause I’ve forgotten all of young love’s joy

Feel like a lady, and you my lady boyHe said ‘the respect I made you earn –

Thought you had so many lessons to learn’

I said ‘You don’t know what love is – get a grip! ‘ –

Sounds as if you’re reading from some other tired scriptI’m not gonna meet your mother anytime

I just wanna grip your body over mine

Please tell me why you think that’s a crimeI’ve forgotten all of young love’s joy

Feel like a lady, and you my lady boyThey tried to make me go to rehab but I said, ‘No, no, no.’

Yes, I’ve been black but when I come back you’ll know, know, know

I ain’t got the time and if my daddy thinks I’m fine

He’s tried to make me go to rehab but I won’t go, go, goI’d rather be at home with ray

I ain’t got seventy days

‘Cause there’s nothing

There’s nothing you can teach me

That I can’t learn from Mr HathawayI didn’t get a lot in class

But I know it don’t come in a shot glassThey tried to make me go to rehab but I said, ‘No, no, no.’

Yes, I’ve been black but when I come back you’ll know, know, know

I ain’t got the time and if my daddy thinks I’m fine

He’s tried to make me go to rehab but I won’t go, go, goThe man said, ‘Why do you think you’re here?’

I said, ‘I got no idea

I’m gonna, I’m gonna lose my baby

So I always keep a bottle near.’

He said, “I just think you’re depressed.”

This me “Yeah, baby, and the rest.”They tried to make me go to rehab but I said, ‘No, no, no.’

Yes, I’ve been black but when I come back you’ll know, know, knowI don’t ever wanna drink again

I just, ooh, I just need a friend

I’m not gonna spend ten weeks

Have everyone think I’m on the mendIt’s not just my pride

It’s just ’til these tears have driedThey tried to make me go to rehab but I said, ‘No, no, no.’

Yes, I’ve been black but when I come back you’ll know, know, know

I ain’t got the time and if my daddy thinks I’m fine

He’s tried to make me go to rehab but I won’t go, go, go