“Nothing can come of nothing” – Cordelia in King Lear

If any character can be said to have an arc, King Lear is the man. In the course of the first half of a play typically 3+ hours long he transforms from a man we are assured was authoritative and commanded loyalty prior to his first appearance, via vain, spiteful, bitter and vengeful to incoherent rage, thence to outright madness post-interval.

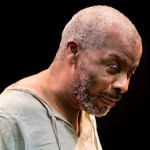

Not everyone would be enamoured with the casting of Don Warrington, a fine and subtle actor best known for a tenure in the sitcom Rising Damp in his 20s, but who I once saw playing a strikingly intelligent and articulate Mark Anthony in Julius Caesar at the Nottingham Playhouse. I am indebted to Clare Brennan in the Guardian for dispelling the curse of unimaginative casting and to demonstrate that black actors are indeed worthy of the great roles:

‘A quote, by Sue Lawley from Desert Island Discs, in the Royal Exchange/Talawa Theatre Company programme surprises: “Can you cast a black person as King Lear? I mean that person… just doesn’t look right, some people might say.” Crazy! An actor is an actor is an actor is an actor. What counts is: can they convince us? The quote is a decade old. Let’s hope it expresses an attitude that is now ancient history.’

I couldn’t have put it better myself. The bulk of the cast in this Lear is black, but that is of no consequence, for the production they offer is compelling viewing, almost a medieval thriller which reaches a heart-stopping crescendo. Credit to the Talawa Theatre Company for ensuring that the ensemble cast is a match for Warrington.

The crumbling of the great man forms the substance of one of Shakespeare’s greatest tragedies and is certainly not a role to be trifled with. No lightweight will do: Lear’s complexity requires an actor of depth and gravitas, able to demonstrate a full spectrum of emotions, all the better to make the character credible and give him a cutting edge. Let’s put this one to bed up front: Warrington is unquestionably a heavyweight, an actor of much light and shade, who brings to the role both the initial wrath and venal raging, later giving way to nobility and dignity.

Michael Buffong‘s version of Lear’s medieval kingdom of England is bleak, earthen, featureless and, apart from a fine coat worn by the monarch, shorn of the trappings of grandeur, let alone joy. The set is designed to look basic: a circle of rough dirty ground is surrounded by an offset walkway, such that the top end is raised and the lower end sunken. The cast are in very traditional dress, which is to say timeless robes and shirts and gowns, as opposed to modern dress productions in which Lear might well turn up in a finely tailored three piece suit.

Props and furniture are sparse, the notable exception being swords with which to fight, this being an embattled kingdom, from which Lear vacates his throne in the throes of madness.

The storm, when it comes, brings real rain down from the heavens, or rather the lighting rig – a ploy recently exploited in The Crucible at the self same theatre. It could have been constantly raining, much like the city featured in the movie Se7en. This somehow reflects the mood of its King, whose voice, even as he makes the huge tactical blunder of dividing his kingdom and demanding the love of his three daughters, forms a rich but gravelly baritone, fraught with paranoia.

Taking out his wrath on the honest and innocent Cordelia (Pepter Lunkuse), whom he banishes not despite but because he is his most loved daughter. However, in so doing Lear fails to spot the jealous scheming of elder daughters Goneril (Rakie Ayola) and Regan (Debbie Korley), Regan’s husband, the vicious and ambitious Cornwall (Norman Bowman) and her impossibly vain and camp steward Oswald (Thomas Coombes.)

Worst of all, he fails to help the hapless Gloucester (Philip Whitchurch) control manipulative bastard son Edmund (Fraser Ayres.) Of the forces for good, Mark Springer‘s Albany proves a more decent soul than wife Goneril, the banished Kent (Wil Johnson) demonstrates loyalty beyond all measure, and the good Edgar (Alfred Enoch) thwarts his evil half-brother Edmund and saves Gloucester, graphically blinded on stage by the strangely Scottish Cornwall.

The treachery is uniformly played with passion and conviction; these scenes are conducted at a rattling pace, contrasting nicely with the scenes where Lear is given time and space to realise how he has blown his kingdom and unleashed tragedy upon himself. In this regard, he enlists the help of his prattling but nervy Fool (Miltos Yerolemou) and the worthy Kent, in disguise, who act as mirror to the worthy King.

“When we are born, we cry that we are come to this great stage of fools” – Lear

It is worth pursuing the relationship between the unravelling Lear and his melancholy Fool, since it struck me more than in any previous production I had seen that the Fool is the flip side of Lear’s personality, the yin to his yang. Not only are they inseparable (apart from Lear’s first scene, from which the Fool is excluded in this production), but they bicker like an old married couple and almost finish one another’s sentences. Separated, they are feeble and incapable of survival. It’s often said that the Fool speaks more sense than anyone in the play, but here he speaks with tremulous wit what Lear feels deep inside – that he is the Fool.

By the time Lear has conquered madness, seen the error of his ways and returned to court, he is too late – his daughters all die, victims of the jealousy that Lear unleashed. As with all tragedies, the hero then realises his life is now over. This powerful moment is played out with pathos; at once we see that all Lear’s paranoia was for nothing – life goes on and the good Edgar inherits the throne.

Emotion notwithstanding, it is also technically adept and demonstrates a sympathetic reading. The heart-stopping blood and thunder fight scenes are as well choreographed as any I have ever seen, and the plucking of Gloucester’s eyes worthy of a horror movie (even if he had his back to us at the time – the downside of theatre in the round!) By contrast, Tayo Akinbode‘s score and sound design brings out the mood of quieter sections brilliantly, even if it is barely noticed while the audience focus on the words.

If I had to be critical, a few characterisations were less than effectual, notably a cameo by the King of France (Miles Mitchell), though perhaps a comment more on the sharpness of other characters. Perhaps I wanted Goneril and Regan to be be more boo-hiss nasty and Cordelia more loveable, but that is my deficiency – all three are human and portrayed with strengths and weaknesses rather than as caricatures. They react to the artificial circumstances in which they find themselves, much as if Lear were magical realism.

This is first and foremost a production of depth, poise and cerebral intent, electrifying to watch and orchestrated with fine craft by Buffong. Lear is the central focus, but neither does he dominate or detract from the players around him – a mark of an actor at the top of his game. Thank you Don Warrington, you did us proud.