There's the banjo serenader, and the others of his race,

And the piano-organist--I've got him on the list!

And the people who eat peppermint and puff it in your face,

They never would be missed--they never would be missed!

Then the idiot who praises, with enthusiastic tone,

All centuries but this, and every country but his own;

And the lady from the provinces, who dresses like a guy,

And who "doesn't think she waltzes, but would rather like to

try";

And that singular anomaly, the lady novelist--

I don't think she'd be missed--I'm sure she'd not he missed!

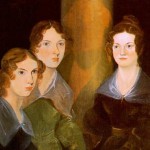

There have been many updates to the words of the eternally sharp-witted W S Gilbert’s famous list song as originally performed in The Mikado. Some seem very hard done-by (what did the piano-organist do to offend him?), but most of all, when Gilbert refers to “…that singular anomaly the lady novelist” he was delivering an undeserved barb to the likes of the Bronte sisters, Jane Austen, George Eliot, George Sand, Elizabeth Gaskell, Mary Shelley and many more great novelists of the 19th Century, not to mention poets, playwrights and writers of other media.

Nor had he foreseen that many of the greatest and/or most popular novelists of the 20th Century would also be women – Du Maurier, Woolf, Atwood, Bainbridge, Allende, Walker, Wharton, Lee, Murdoch, Spark and Carter, to name but a few. What, you wonder, would he have made of the female detective fiction of Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh, Ellis Peters and Dorothy L Sayers, for example, once a very macho preserve.

What indeed did he have against female authors, other than his misogynistic tendency to sneer at any achievement by women? Ian Bradley, writing in History Today, says this:

W.S. Gilbert… is generally viewed as a crusty Victorian gentleman exhibiting in acute form the typical prejudices of his age and class, notably complacency, misogyny and xenophobia.

But also…

Gilbert was first and foremost a satirist with a keen eye for hypocrisy, pomposity and absurdity. His targets were sometimes social and cultural, like the English class system which he lampooned in HMS Pinafore (1878) and the preciousness of Pre-Raphaelite asceticism which he pilloried in Patience (1881), but predominantly he went for institutions, like the police force which is sent up so gently but effectively in The Pirates of Penzance (1879). His two most consistent targets were the Church of England and the political system but he was thwarted in his satirical sallies in these two areas by public taste, critical opinion and the censorship of the lord chancellor, as well as by his own timidity and reluctance to offend, all of which had the effect of emasculating and weaken- ing the force of his barbs.

Possibly one objection to the female novelist could be that it was generally the preserve of ladies of a certain class and social standing who did not actually have to work for a living and who therefore had plenty of time, but as a rule no experience of life on which to base their writings – where working class women of the time would not have the opportunities or necessarily the skills to write, let alone to get published. The same might equally be said about many male novelists, though it was certainly more acceptable for a man to adopt a career as novelist than for a gentle lady. Social commentary and satire was popularised by Dickens in particular, acting as a voice for the poor and needy, and awaking consciences in Parliament through his words, but he was far from being the only such campaigner.

Several of these lady novelists, from the position of comparative wealth and advantage, such that many could afford to self-publish, but many did make an effort to discover the world of social deprivation only a short distance from their well-to-do circles. Mrs Gaskell, a close friend of Charlotte Bronte, Charles Dickens, John Ruskin and various social reformers, and became engaged in many activities to help the poor and needy. She visited prisoners and with the help of Dickens used one (known only as Pasley) as the model for the hero of her novel Ruth. This was not untypical: many female novelists wrote to voice social concerns, often under noms de plume – primarily because it was seen to be unworthy of a gentlewoman so to do.

Lady novelists may have been a minority group, but their works have stood the test of time and often been hailed retrospectively as classics. So we will put Gilbert’s line down to a touch of misogynistic grumpiness and the need to fit in a line which stirred up debate among its viewers. In that he probably succeeded!