There were many firsts in Phyllida Lloyd‘s adventurous production of Julius Caesar, part of a fascinating yet contrasting all-female trilogy comprising The Tempest and Henry IV (parts 1 and/or part 2 unspecified) at the Donmar’s temporary venue around the corner from Kings Cross station.

Given that I was wiped out by watching a matinee and evening performance, quite apart from the occasions where I’ve had to perform twice on the same day, I am awe struck with admiration for the energetic cast who were performing all three plays on the same day, with just a two-hour break between each. To do that you need true stamina, so all the workouts will have paid dividends. But I digress…

Perhaps the most dramatic first was that Julius Caesar him/herself was assassinated literally inches in front of me (in the centre of row A in fact), including an un-Shakespearean bottle of bleach being poured down his/her throat as well as being repeatedly stabbed with stage knives, but more of that anon. This production broke boundaries at every level, a common phenomenon where a director wishes to challenge audience expectations.

This commenced in a packed foyer where “prison guards” led “prisoners” through to the “exercise yard” before we were led to our seats with dire warnings that this was a 2-hour performance with no intervals. This, you see, is Shakespeare as performed by female inmates protesting against violence by men and incarceration of women – and, indeed, that the metaphor describes the lack of liberty in Caesar’s Rome – not greatly improved thereafter in spite of the clarion cry of Freedom!

This is a running theme through the Shakesperiean power games, ultimately male power games, reinforced by physical environment, replete with cages and reinforced fences. This mirrors the claustrophobic feel, such that you could easily believe the play was being performed at Pentonville.

Especially in the second half of the play (edited to a manageable two hours, including interventions by the guards decidedly not written by the bard), the aggression and conflict of battle are highlighted by deafening shock tactics of metal music, the rapid-fire rattle of gunfire emphasised by drum tattoos. It was at times, as my son might put it, a bit too in yer face.

This rich stew of noise and context is highly inventive and undoubtedly brilliant its way, but the production is at its best when it sticks to the light and shade of Shakespearean text, performed as intended. For example, the early scene between Brutus and Cassius was a model of incisive delivery and vocal clarity, demonstrating to fabulous effect the subtle talents of Dame Harriet Walter and the eloquent range displayed by the hugely impressive Martina Laird.

As the plotting of the conspirators progressed, Caesar is killed and the action becomes increasingly frenetic with a matching crescendo of sound, so the emotional subtlety is drowned out. It’s not that such climaxes do not have a purpose, but the sheer relentlessness of sound and action produced diminishing returns. As my companion put it, you don’t want rich food all the time – sometimes beans on toast is all you need. A more varied diet might have helped the digestion?

The other aspect that interfered with the coherence and continuity of performance were the prison interventions, notably where the play halts as the likeable Scottish Casca (Karen Dunbar) is halted pretty much mid-sentence as the lights go up and a canned warder’s voice sends prisoner Alexander to take her meds. This is a great shame, since many scenes are handled brilliantly and will stand long in the memory.

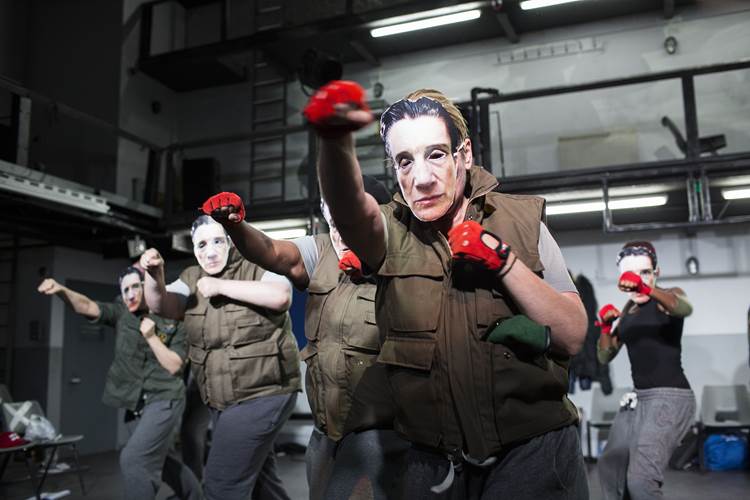

For example, the signifying of bloodied hands with red rubber gloves was a master stroke; the repeated shooting of a hooded victim spoke volumes; the appearance of the soothsayer on a melodically squeaking tricycle with a doll was such an evocative touch – it reminded my friend of Big Ears in children’s Noddy books. In fact, the menacing and sinister touches are everywhere to be seen in Lloyd’s vision. Who could forget the conspirators dressed in tribal grey hoodies and face masks? Much of what we see works a treat.

What of the characters? Jackie Clune‘s Caesar exudes a natural authority, symbolised by the black leather coat, which mantle is later adopted by Mark Anthony and subsequently by Octavius as each assumes power. Her ghost looks on balefully in later scenes from a halo of shimmering light.

Talking of accents, worth mentioning that a poised and moving pregnant Portia (Clare Dunne) is played here in an Irish accent – but then the melting pot of backgrounds would be authentic to a prison, just as the far-flung ethnic and cultural backgrounds among the players are both welcome and effectively utilised. Her scenes with Brutus are achingly tender, beautifully played.

Here is another dramatic moment: the last time I saw JC was many years ago in Nottingham, where Don Warrington‘s Mark Anthony delivered his famous “Friends, Romans, Countrymen” speech (see below) to Risorgimento Rome as a prayer for peace, a cute politician’s plea for unity.

Here, Jade Anouka‘s Mark Anthony delivers the same speech mostly pinned face-down to the ground by the conspirators, which certainly gives a fresh perspective, a reinterpretation of the power structures in Shakespeare’s text, as if the character is pleading more for his life. Anouka begins her interpretation of MA as a cocky East-Ender, but the character becomes wiser and grows in stature through the play, which arc is the hallmark of a part well played.

Then there is the senior performer and star. A much decorated and honour actress, Harriet Walter has spent a career playing with distinction noted character roles in period drama, and fondly in my memory Harriet Vane in Dorothy L Sayers mysteries. In real life she is smaller, more slender than her TV image might suggest. On stage in very masculine clothing she appears wiry yet vulnerable, her voice less strident than one might imagine. Her Brutus is an idealist with a conscience and a plague of secret doubts, one who at the death seems far more fragile than his noble and fearsome reputation might suggest. As the character himself puts it:

Cassius,

Be not deceived. If I have veiled my look,

I turn the trouble of my countenance

Merely upon myself. Vexèd I am

Of late with passions of some difference,

Conceptions only proper to myself,

Which give some soil, perhaps, to my behaviors.

But let not therefore my good friends be grieved

(Among which number, Cassius, be you one)

Nor construe any further my neglect,

Than that poor Brutus, with himself at war,

Forgets the shows of love to other men.

Without such doubts and weaknesses, maybe Brutus could have fought off his enemies and assumed power and won popular appeal among Romans – though sadly he/she is still incarcerated, so not to be. The end of Brutus is slightly bizarre, since (s)he runs on to a hail of bullets from a toy gun rather than the more traditional sword, as described in the text, but that’s what happens when you play fast and loose with Shakespearean settings.

It is these aspects of personality and motivation that bring out the best in the poetry of the bard, and which would have made this ambitious and impressive Julius Caesar better still, but make no mistake, this is a muscular show that bites back, eschews soft hearts and is not afraid to shout out loud. Art should leave an impression, not merely be, as Frank Lloyd Wright said of television, “chewing gum for the eyes.”

Of its audiences, all will walk away feeling stunned and trying to absorb the full terror of what has been seen. In this case, that included Jeremy Vine and his teenage daughter, further along our row; I trust this gave him something to talk about on Radio 2.

Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears;I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him.The evil that men do lives after them;The good is oft interred with their bones;So let it be with Caesar. The noble BrutusHath told you Caesar was ambitious:If it were so, it was a grievous fault,And grievously hath Caesar answer’d it.Here, under leave of Brutus and the rest–For Brutus is an honourable man;So are they all, all honourable men–Come I to speak in Caesar’s funeral.He was my friend, faithful and just to me:But Brutus says he was ambitious;And Brutus is an honourable man.He hath brought many captives home to RomeWhose ransoms did the general coffers fill:Did this in Caesar seem ambitious?When that the poor have cried, Caesar hath wept:Ambition should be made of sterner stuff:Yet Brutus says he was ambitious;And Brutus is an honourable man.You all did see that on the LupercalI thrice presented him a kingly crown,Which he did thrice refuse: was this ambition?Yet Brutus says he was ambitious;And, sure, he is an honourable man.I speak not to disprove what Brutus spoke,But here I am to speak what I do know.You all did love him once, not without cause:What cause withholds you then, to mourn for him?O judgment! thou art fled to brutish beasts,And men have lost their reason. Bear with me;My heart is in the coffin there with Caesar,And I must pause till it come back to me.