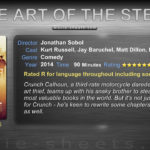

Heists. One of our favourite genres, no? You loved Oceans, The Italian Job (the original anyway), The Thomas Crown Affair (both versions), The Usual Suspects, Inside Man, Lock Stock, Gambit, and, if you’re a connessieur of the genre, maybe even the French masterpiece Rififi. Heard of The Art of the Steal though? Quite possibly not, in spite of a stellar cast.

There are usually good reasons why a film does not make it big, many of which relate to leaden pacing, stilted script, wooden acting, bungled action sequences and lousy direction, such that the audience does not give a tuppenny damn if the bad guys end behind bars, though in the best traditions of the Hays Office they won’t get away with the loot. Or will they? Things are a bit different nowadays…

So are we talking about a total clanger here? No. The Art of the Steal is a good but not a great movie; then again, neither is it so awful that you wouldn’t give it time of day. There is humour, as humour there must be. The plot is silly but not so silly that your credulity snaps, and indeed OTT delivery goes with the turf. The pace is rattling but not so fast you lose all track of plotting detail.

There is a neat twist you will probably see coming a long way off, but it’s set up nicely and delivered with panache and an ending you’d have to be hard-hearted to find anything other than satisfying. In fact, I’d go so far as to say it avoids cheating the audience as did, for example, Now You See Me.

Tell the truth, director Jonathan Sobol does a decent job and the guys (for there is not more than the token woman on board in the misogynistic world of the art heist) all look like they’re having a bloody good time, especially in the outtakes thoughtfully provided in the closing credits.

First good move was recruiting Kurt Russell as lead, the same Kurt Russell we saw grappling with an alien life force in The Thing, and indeed the same Kurt Russell who did a fine job recently in The Hateful Eight. Russell contrives to be an action star but with a touch of cerebrally enhanced performance such that you know something is going on in that wrinkled brainbox.

All the cast is blameless, each playing well with the possible exception of Jay Baruchel‘s screechingly hammy apprentice, Francie Tobin. Worthy of commendation is the duplicitous Nicky Calhoun (Matt Dillon), brother of Kurt’s Crunch Calhoun, played with charm and an evil twinkle by turns. Have to say I was quite fond of Uncle Paddy (Kenneth Welsh) too, for all heist movies have an old lag with a touch of wisdom.

So in view of the good ingredients, why did The Art Of The Steal bomb at the box office ($61,446 wouldn’t pay for the meanest of post-production parties) and gain sniffy reactions from critics? The Rotten Tomatoes consensus view is quoted on Wikipedia, and gets right to the nub:

“It boasts a terrific cast led by the always-watchable Kurt Russell and Terence Stamp, but The Art of the Steal wastes its stars on a formulaic plot that borrows too obviously from superior heist pictures.”

In other words, travelling the same ground in me-too fashion, right down to the flashy graphics of the titles. Yes, it does cover familiar turf. No question that the film follows the linear 3-act formula of the heist, recounted on Wikipedia:

Usually a heist film will contain a three-act plot. The first act usually consists of the preparations for the heist: gathering conspirators; learning about the layout of the location to be robbed; learning about the alarm system; revealing innovative technologies to be used; and, most importantly, setting up the plot twists in the final act. The second act is the heist itself. With rare exception, the heist will be successful, although some number of unexpected events will occur. The third act is the unraveling of the plot. The characters involved in the heist will be turned against one another or one of the characters will have made arrangements with some outside party, who will interfere (often a wise, underestimated detective).

So undeniably formulaic and borrowing more than a few cues from other heist movies. Granted that on this occasion, the rules are subverted in at least one degree by following the modern trend hinted at above:

Normally, most of or all the characters involved in the heist will end up dead, captured by the law, or without any of the loot; however, it is becoming increasingly common for the conspirators to be successful, particularly if the target is portrayed as being of low moral standing, such as casinos, corrupt organizations or individuals, or fellow criminals.

In fact the law comes in the form of the obtuse Agent Bick (Jason Jones) with, as his reluctant sidekick and art expert by threat of imprisonment, the wonderful Terence Stamp‘s Samuel Winter, by far the most sophisticated and complex character on view.

Frankly, Agent Bick is a lumbering opponent, clearly not capable of matching the wits of our beloved gang, and maybe that is a problem in itself since the best heists require a worthy opponent on the right side of the law. In fact, the essence of the movie is that Nicky has betrayed Crunch, who serves years in a Polish prison on his behalf, which rivalry is the spine of the plot.

Shame but there you have it: if you want to win favour in the crowded marketplace, you have to be bigger and better. Cast alone can’t steal it, and no matter how clever your plotting you need a USP. Art heists have been done before, so you have to look slightly off-kilter and come at it from afresh. Tarantino managed this in Reservoir Dogs by virtue of ignoring the heist itself and focusing instead on the aftermath. So nice try Jonathan, but next time give us an angle.