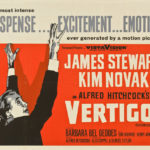

Perhaps this is more a story about my fondness for the art of Hitchcock, and especially his cunning use of the art form and technology to stay one step ahead of audiences. If you think his films look dated now, remember that they were cutting edge.

For a prime example, where better to look than Vertigo, a movie that has, over time, been reappraised in the public consciousness and reclassed from thriller to classic, to the extent that a poll of distributors, critics and academics once awarded it the title of best film of all time. That would be a pointless exaggeration of the film, one that would surely be rejected by Hitch, who once famously described Psycho as a “comedy,” though it does demonstrate that the virtues of the master of suspense’s finest works exceed mere formulaic and manipulative thriller genre. This quote from one analysis certainly tells you of the film’s coherence:

“Vertigo somehow seems to transcend these concerns and instead offers a compelling psycho-drama that has complex layers of meaning and employs carefully crafted film language to present a narrative that aligns the audience so completely with the protagonist.”

On the face of it, the bones of the plot, culled from a French thriller called D’Entre Les Morts by Pierre Boileau and Pierre Ayreau (aka Thomas Narcejac), who collectively were known as Boileau-Narcejac, is nothing particularly remarkable. A detective who suffers from vertigo (actually an inner ear condition in which objects appear to move when they are stationary) and acrophobia (which is fear of heights but not such a catchy title), is played by his friend Gavin Estler (Tom Helmore), who wants to get rid of his wife and does so by concocting a plot in which Scottie is trapped, hook, line and sinker – though realisation gradually dawns and the ending follows in imitable style.

As with other works from the master, this plot is not revealed at the end but 40 minutes earlier, allowing the dynamic to change and suspense to build again before the thrill of the ending. For sheer cunning and manipulation, few if any could beat Hitch, but the question you might want to ask is whether this is his masterwork, and if so, what makes it that special? A few ideas follow, though you may have a few of your own. The critics certainly had their views – from Wikipedia:

Critics have interpreted Vertigo variously as “a tale of male aggression and visual control; as a map of female Oedipal trajectory; as a deconstruction of the male construction of femininity and of masculinity itself; as a stripping bare of the mechanisms of directorial, Hollywood studio and colonial oppression; and as a place where textual meanings play out in an infinite regress of self-reflexivity.”

Fact is that an expert filmmaker can turn a relatively straightforward tale into something special by playing with the audience’s expectations, then subverting them by sharp mood changes. In short, Hitch deliberately played with the subconscious through imagery and effects.

These were developed in Scottie’s nightmare scene with the spiral effect, disorienting effects (including Stewart’s green-tinged head against a purple spinning background.) Dreams are a device Hitch had used before, notably in Spellbound, but which in 1958 including an elaborate animated sequence worthy of a deranged Disney movie and was the forerunner of CGI. In his bid to unsettle audiences, Hitch went places no other director thought to go, which makes you wonder what he would be doing now, were he at the peak of his powers in 2017.

As a technical work, Vertigo was groundbreaking – undeniably the best of its day, much in the same way that Psycho, The Birds and Rope were masterpieces of technical ingenuity from way before the days of CGI. But you have to peel back the myth to see how effects were created by extending the capabilities known previously – and in employing these to achieve groundbreaking effects, much as Welles did in Citizen Kane.

For example, this was the first film to use dolly zoom, whose effects enabled Hitch to amplify the effect of John “Scottie” Ferguson’s medical condition for the benefit of the audience by distorting perspective. This happens in the initial rooftop chase scene, but later in the bell tower and other points in the film, and very effective it is too. In fact, it’s known as the “Vertigo effect” to this day.

Even the conventional photography is quite beautifully rendered, particularly in its restored format. It is filled, deliberately, with rich primary colours, much in the same way West Side Story used colour to demonstrate the straightforward contrast between the two gangs. The colours come sharply into focus as the cast switches from red to green when Kim Novak‘s Judy Barton (aka Madeleine Elster) is identified beyond the scam pulled on Jimmy Stewart‘s Scottie – she is wearing green in a room with a bright green hue (for more on this topic, do read this informative analysis.)

Hitch’s deliberate use of iconic visuals was also exemplified in his locations, notably the (red) Golden Gate Bridge and, even more famously, the Mission San Juan Batista (in which the bell tower burned down by fire was recreated with miniatures and studio sets) in Vertigo – but this is far from the only instance. Remember the use of Mount Rushmore in North by North West, London landmarks in Frenzy, among many more examples? These were places the audience could relate to, contrasting to the now equally iconic but disoriented location of the Bates Motel in Psycho.

Of course, Hitch had his trademarks, and Vertigo is no exception. His customary cameo appearance is a source of light relief, and the use of a beautiful blonde heroine in Hitch’s movies, Novak in this case, has been much discussed. That said, you feel sorry in this case for Barbara Bel Geddes‘s Midge Wood, who deserves more than being classed as Scottie’s platonic buddy and (very) brief fiancée, but then the director always was particular about his women.

Whether Vertigo is the best in the Hitchcock oeuvre, let alone of all time, is highly subjective. While many seem to consider Psycho his masterpiece, my own small straw poll via the Film Buffs group on Facebook seemed to rate Rear Window more highly. In some ways this is a more homely and humorous movie, even if it also does something then unique in film (focusing on activity in a block of flats opposite, creating these as a set in the studio.)

However, I still regard Vertigo as the more remarkable achievement in narrative and technical genius. Given that NBNW, Psycho and The Birds followed, it tells me that Hitch was still in his most productively innovative period.