“At some point you’re no longer growing up, you’re ageing. But no-one can pinpoint that moment exactly” – Richard Linklater

This is one of those reviews where you can’t do right for doing wrong, for the film I am reviewing polarises audiences, splits them asunder. This I know because I did some field research using the Film Buffs group on Facebook, where the opinions were roughly divided by those who were bored out of their skulls and those who considered the film a masterpiece. I shall return to this debate later, but first an introduction concerning the nature of reality in film-making.

The search for authenticity in film-making knows few limits. Killing your actors is generally frowned upon, and to be fair only usually happens by accident (viz, Vic Morrow and Brandon Lee), but there’s not much off the agenda. It extends to applying The Method, which actors do routinely and sometimes to ludicrous extents, but directors too. We’ve all heard about Hitchcock and Kubrick terrifying the living daylights out of actors (Tippi Hedren and Shelley Duvall respectively being prime examples) in order to capture genuine fear on the film reel, but such extreme lengths are not always necessary.

In the case of Richard Linklater‘s coming of age Bildungsroman drama among everyday Houston folk, Boyhood, the primary device was to write and shoot in real time over 11 years so the children grew up and the action was built on the previous year’s footage. It is done with familial love and affection, such that fiction and reality are mingled.

The time lapse technique won rave reviews from critic and an assortment of gongs, though only an Oscar for Patricia Arquette as best supporting actress. From Wikipedia:

Production began in 2002 and finished in 2013, with Linklater’s goal to make a film about growing up. The project began without a completed script, with only basic plot points and the ending written initially. Linklater developed the script throughout production, writing the next year’s portion of the film after rewatching the previous year’s footage. He incorporated changes he saw in each actor into the script, while also allowing all major actors to participate in the writing process by incorporating their life experiences into their characters’ stories.

On one hand, this is a rambling epic (pushing 3 hours) about the trials and tribulations of life in one extended modern family, comprising two divorces, a remarriage and a new household combining the children of two defunct and complex modern yet ordinary American families.

As such, it feels like a saga rather than a planned narrative, incorporating the ingredients of a soap opera, but then condensed from a decade into movie format. The way it was created makes this movie a perfect match for naturalistic acting, so that’s what you get in spades. Any more sophisticated or layered style would not suit this technique.

Nothing especially revolutionary, you might think, and you’d be right. All the traits of complex modern family life, all the cues you expect to find in rights of passage movies, no uniting theme or purpose, other than the impact of slow and gradual ageing – this ageing to maturity being the story arc. just goes to show that nobody is exempt from the effects of where growing up turns to ageing – as suggested by Linklater’s quote, featured above.

What works is emotional familiarity and complexity of relationships, real and dramatic, such that Boyhood has a three-dimensional feel, contrasting with the trite and brittle relationships we have come to expect of soapish kitchen sink dramas – though some would probably describe Boyhood as a being more akin to a fly-on-the-wall home movie than fictional drama in the conventional sense. This is not a quality you can paint on by the yard; it is intangible and comes through body language and subtle inferences of comfort, familiarity, affection – and also discomfort and conflict.

However, while it scored a hit in film circles, this does not automatically mean Boyhoodis a movie you would want to sit through, nor that you would necessarily find it entertaining if it is essentially actors telling you what goes on in your own family life. On the contrary: I suspect for some it would be rather too close to the drab reality that a good number go to the cinema to forget for a few brief hours. I have sat through some truly heavy films, but did find my attention wandering after the first 90 minutes or so.

While escapism has its place, grit is high on the film-making agenda these days. Sure enough, Boyhood has gritty moments in isolation, plus highs and lows – but probably less drama than in your average episode of Eastenders, and certainly no dramatic tension or building suspense – precisely because it lacks a narrative structure. Don’t expect too many revelations or revolutions, just evolutionary development in real time and people talking the same smalltalk they would in real life.

In fact, you could say that since Linklater incorporated aspects of the actors’ lives into scenes in his script, it’s not really acting – but is The Method brought to life through improv. Hell, he even cast his own daughter, Lorelei, as older sister Samantha, and if that’s not keeping it in the family I don’t know what is!

There’s no denying that the cast go along with the film’s notion with some considerable ease. While Arquette won the biggest plaudits, I was impressed with Ethan Hawke‘s Mason Sr, perhaps more so than any other of his films by virtue of plausibility as a slightly flaky and dysfunctional dad who plainly loves his kids.

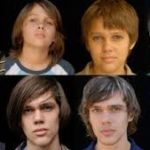

The children who grow into adults do every bit as well, notably Ellar Coltrane‘s Mason Jr – though very noticeable that the impact of the ageing process from 6 to 18 diminishes as he gets through adolescence and the growing up becomes behavioural. Arquette’s Olivia stays blonde but ages noticeably about the face, certainly not more glamorous with age. Meanwhile, Mason Sr acquires a moustache of the variety you wish you could rip from his face. The stress and anxiety of living with growing children is etched on the faces of the adults, as it would be in real life – assuming you can divorce Boyhood from real life.

Whether all this constitutes a “classic” film you can decide for yourself. In essence, I can admire quite a few of the qualities Linklater strove to imbue in his work, but the overall effect led me to think, “so what?” For those who consider this to be a masterpiece, I’d ask why? What is there to make this a great film? Empire magazine says this:

“Linklater’s beautiful film is an extraordinary achievement — tender, funny, wise and wistful, full of warmth and humanity.”

Wistful maybe, not especially funny, nor wiser than the accumulated wisdom found within any growing family. Warmth and humanity? I find more credible the words of the Film Buffs reviewer who concluded:

“Was really looking forward to it, loved the premise but the execution was lacking. Only watched an hour due to just being bored, and had no interest in the story or the characters :(“

My views are tempered only by Arquette’s speech near the end: “I thought there would be more.” How very true!