My old dad would never have clocked this trend. In his day you got a job and worked for the same company for the foreseeable. In hindsight he wished he’d branched out on his own, formed his own architectural practice, worked hard and make a success of his life. The point to both options would have been the same: you stuck at what you do and improved your reputation over time, through dedication. The point to either route was permanence.

The trend takes people away from regular employment, but it’s taken place gradually over a long period. Sure there was always seasonal work, among the fruit pickers for example. Lots of IT contractors have been freelance for many years, often employed on a project basis; and indeed interim managers, employed, for example, during spells of maternity leave or pending recruitment of a new role.

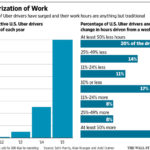

Some casual roles were always subcontracted, taxi drivers and couriers chief among them, but suddenly everywhere you look people were hired on a self-employed basis, since it reduced admin, cut NI payments, transferred PAYE responsibility and allowed staff to be hired and fired in short order without protection. More than that, many roles in factory assembly and call centres, to name but two, have been based around piecework for many years, linking earnings to productivity as a means of overcoming payment based on time worked.

Superficially, this might increase short-term earnings but the lack of pensions and other benefits, let alone the constant risk of unemployment makes it much the trickier in the long-term. As you get older, chances are that people may find themselves less attractive unless they happen to be, say, retired High Court Judges or politicians (see here.)

So far so good, but then another element was thrown into the mix: you were paid for what you do and nothing inbetween. There are now a million plus on the so-called “zero hour contracts” whereby the people concerned are never guaranteed hours, even when these are primarily at minimum wage in professions such as caring, cleaning and, famously, working in Sports Direct warehouses.

Convenient for employers but risky and unreasonable for employees who suddenly find they can’t earn enough to pay their bills. Some get more hours than they can cope with, often in This leads to abuses, where, for example, someone turns down hours and is then offered no work unless the organisation is not able to recruit sufficient specialist skills.

For relatively unskilled professions like caring, the balance of power shifts towards the employers, who can ensure the employees are a non-union workforce and therefore do not have the benefit of collective bargaining on pay, hours, sick and holiday leave, wrongful dismissal claims and more besides. In other words, abuse of workers is on the rise, and there is little the workers can do about it.

The reduction in employee rights is the aim of government, under the pretence of increasing “flexibility” in the labour market – though opposition has certainly pressured ministers to give these employees greater protection from exploitative and abusive employers, of whom there are potentially plenty. The restaurant trade is a prime example, where recent controversies include long hours, payment under minimum wage and service charge going direct to the restaurant owners.

Taking the healthcare market as the other extreme, the shortage of skills has meant doctors and nurses could earn far more from desperate Trusts for working on a locum basis via agencies, to the extent that government cried foul and tried to stop agency staff being employed. This is not a level playing field, such that when it is to the benefit of members of staff the rules get changed.

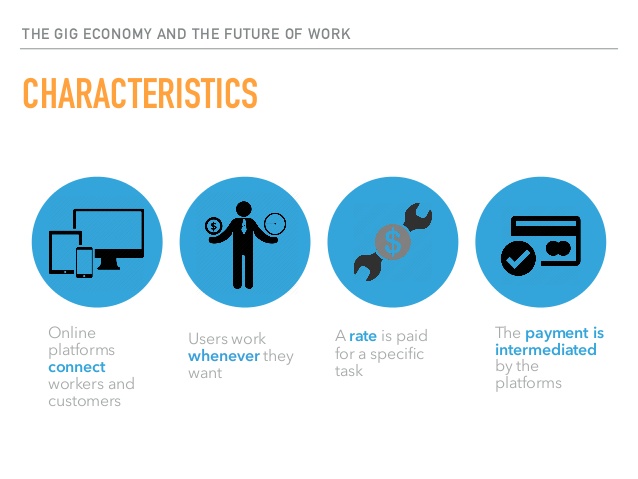

But things are constantly evolving, and it’s smartphone apps that proved the catalyst. Here’s the rub: put together the trend towards freelancing, piecework and just-in-time service requirements, plus technology accessible to all, and what have you got? The gig economy, that’s what – a contingent workforce, “flexible” in the eyes of the employer, opportunistic for parties in the transaction and portending of a massive change in the way the population earns its living.

Proponents would say it’s the perfect example of capitalism in its purest form – a free marketplace where services are bought and sold for a price agreed at the time. Use whatever assets you have: hire out a room via AirBnB; use your car and be an Uber driver; buy and sell via eBay or arts and crafts via Etsy; deliver takeaways with Deliveroo, utilise a parking space someone can hire via ParkingPanda; share a lift with LiftShare; find a competent handyman for tasks at home via TaskRabbit or conduct professional jobs via Freelancer; raise money via Crowdfunder – the list is limited only by the imagination of those who create the marketplace to bring together buyers and sellers of whichever service for which demand exists.

Proponents of the so-called “Gig Economy” say that while traditional jobs are disappearing, we should be happy about the new spate of “entrepreneurial” jobs that will replace them.

In a sense, this takes me back to the ultimate low-tech service economy – India, where railway porters outnumber passengers three to one, where they will mind your shoes when you go into a temple, where baksis is an art form, where for a few rupees you can find anyone to do anything for you on a just-in-time basis.

The advent of technology merely made it easier to achieve virtual connections. Going back in time, early marketplaces were like the original online flower wholesale market, where people could take advantage of buying these perishable goods as quickly as possible from wherever they happened to be, cutting out a shoal of middlemen. The issue was that you had to be a big-time player to take advantage of the volume transactions, so the effect of smartphone apps is to reduce each requirement to a micro-task, requiring no major infrastructure and little investment.

Take one example – Fiverr.com. Here for example, you can declare a service and a price, then open it up to all takers who need something doing, for which they are prepared to pay good money. I considered offering my services for voice talent at a given rate per 100 words, plus discounts for greater quantities. I could post a sample to give people an idea how my voice sounded, and they could commission me directly with no agents, no fees, no contracts.

It sounds great, but to make a living from this source you would need to sell at an absurdly high rate, which is why anyone working solely from contingent sources would probably need at least half a dozen “jobs” – and even then would have slack days in which they could not guarantee any income. Presumably we stick to the entrepreneurial spirit and find more ways to prostitute ourselves (and that option has been suggested, so I hear!)

So what’s the problem with contingent work, ask the politicians? Simple: You are only as good as your last gig, which of course is not something that impacts those at the top.

True, we won’t have paid vacations, retirement plans or sick leave, or much pay for that matter, but we’ll be independent, free as a bird to fail or succeed.

A right-wing government would regard this as a heaven-sent opportunity to make the population self-reliant entrepreneurs paid according to their efforts, off benefits and thereby cutting dependency on the state.

A left-wing opposition would point to the lack of security or guarantee of income means you can never plan your life, indeed the crumbling of the very fabric of society, and would have an unlikely ally in the mortgage industry, since it is highly unlikely such workers could get a mortgage or life insurance. It is already difficult for the self-employed to obtain financial products, since they have no guaranteed income to guarantee mortgage interest or other loan payments, and could easily find themselves falling below minimum criteria in an uncomfortable echo of the causes of the 2008 financial crash.

Indeed, people dependent on turning their talents to some micro-earning transaction will make any insurance difficult to obtain, but doubly necessary in case where sickness or any unforeseen eventuality could see them launched into poverty at breakneck speed, or where liability insurance is required as a prerequisite. Increasingly, that is a risk people gaining work on a contingency basis may have to live with – that they are perpetually one step removed from their entire world might falling apart.

Fast forward to where the government would want us to be in healthcare, there may come a time where treatment is no longer free at the point of delivery, and, as with the US, we may get to the state where rising insurance costs and the fragmentation of the workplace mean people can no longer get “permanent jobs” with sponsored insurance and cannot afford to fund themselves without a basis of free care. Companies dependent on profit will cut jobs without a care in the world.

Worse still, contingent workers may find themselves in a double bind. The Guardian reports on one of the contractual issues facing workers, namely that they may have penalty clauses that reduce the risk on employers but leave the employee in debt (see article repeated at the bottom.)

But what of conventional lifestyles funding on the basis of secure jobs with loyal workers?If this sounds a nightmarish, remember that loyalty on both sides is a fraction of what it was even in my lifetime. People rarely work for one employer for the whole of their working lives, and may have to reinvent themselves four or five times in a career.

Some people don’t want the hassle, but will have no choice but to be resourceful when the entire world of work is based on short-termism. Not a very comfortable thought for our children. Mine are talented, but even so the chances are that they will find themselves having to work freelance and take all the twists and turns of the free market in order to scrape a living.

Parcelforce couriers who deliver packages for Marks & Spencer, John Lewis and Hamleys can be charged up to £250 a day if they are off sick and cannot find someone to cover their shift.

Details of the policy applied by the Royal Mail-owned business emerged days after rival courier company DPD was criticised for charging some drivers who take time off for illness. And it will fuel concerns about precarious working conditions in the “gig economy”, amid a series of disputes about the employment status of people who work for firms such as Uber and Deliveroo.

About a quarter of Parcelforce’s 3,000 couriers are self-employed owner-drivers, meaning they are paid per delivery and must fund their own vehicle, fuel, insurance and uniform. It has emerged that some owner-drivers who take a day off due to illness, but cannot find cover, are being told they must pay Parcelforce £250 per day missed.

The sum is meant to cover the cost of finding a replacement courier. Parcelforce’s self-employed couriers typically earn about £200 for a shift of 12 hours or more, meaning the added penalty can see them lose out on £450 a day if they are ill.

One courier, who asked not to be named for fear of being blacklisted, said drivers were being unfairly punished for illness, while many felt unable to take any holidays. “We all hate it,” he said. “My colleague handed in his notice after being told he was being fined £750 for being off sick for three days.”

He added: “If we’re off sick, we don’t get any payment at all but we still have the same costs, apart from fuel. We have to pay for the van and insurance and there is also the threat hanging over us that if we don’t cover our contracted area, they say we have to cover their costs in bringing in agency drivers to cover the work that we don’t do. We then get charged £250 a day.”

The courier said the decision on whether to charge sick drivers was “entirely at management discretion”, meaning some drivers are penalised while others are not. He added: “The manager suggested to me that maybe five or six of us should get together and employ someone off our own back to cover our runs if we’re off sick.”

The courier said he typically earns about £600 a week before tax, once the cost of fuel and insurance is taken into account. Parcelforce organises the rota patterns for its self-employed drivers and also requires that they undergo three days’ unpaid training. Parcelforce parent Royal Mail, which was floated on the London Stock Exchange in 2013 and is no longer government-owned, made a profit of £742m last year.

In a statement, Parcelforce said: “At Parcelforce, around 75% of drivers are employees with the remaining 25% owner-drivers, who are contracted on a self-employment basis. Self-employed owner drivers working with Parcelforce can expect average earnings from £45,000 to £70,000 per annum.”

“As self-employed subcontractors, they are contracted to ensure the services are provided but not to provide them personally. Many owner-drivers do not actually do the route themselves, but employ someone to do it for them. Self-employed owner-drivers agree to cover the cost of fulfilling their routes if they are unable to do it themselves and are unable to provide cover. Parcelforce ensures that collections and deliveries are carried out and that customer service levels are met.”

Frank Field MP, who chairs the House of Commons work and pensions committee, said: “It almost looks as though some companies are now engaged in a bidding war, to see who can slap the biggest penalty on workers who are sick.

“Again it goes to show how badly we need a national minimum level of decency to be enforced in the gig economy, alongside a national living wage, so that workers aren’t ripped off by the companies they work with.”