Tzara: Oh, what nonsense you talk Carr: It may be nonsense but at least it's clever nonsense

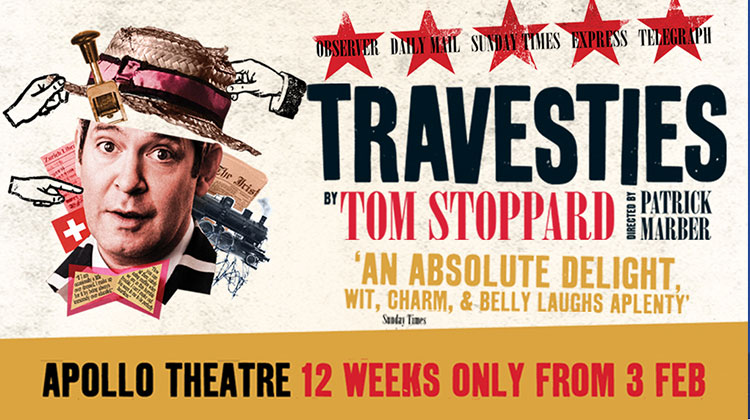

Word of the day is dazzle, along with dazzled and dazzling. You’ll read it quite a few times in this review. It is there deliberately, for this production of Travesties is, of course, bedazzling.

Travesties is, typically for our greatest artistic import from the then Czechoslovakia via India, Sir Tom Stoppard (aka Tomáš Straussler), a dazzling achievement. It is intellectual without being dull and packed with witty word-play, effervescent characters and nods aplenty to the erstwhile greats of art, literature and politics: Wilde for the architecture of The Importance of Being Earnest; and James Joyce (of Ulysses fame), Tristan Tzara (co-founder of the Dadaist art movement and founding member of Cabaret Voltaire) and Lenin (catalyst of the Russian revolution) as characters living temporarily in Zürich, in much the same way that Terry Johnson‘s Insignificance gathers Monroe, Einstein, DiMaggio and McCarthy in a New York hotel room.

The rich stew of ingredients does not of itself guarantee the finished product will be a product of genius, and indeed the word “intellectual” does have a tendency to scare off a proportion of UK audiences who do not want to be found wanting in their ability to hold and manipulate random abstract theories. But the joy of Stoppard plays is that they are also dazzlingly entertaining and fizzing with humour and invention by turn, such that you can appreciate them at many levels, a feat that has left him feted and enjoyed by many.

Michael Billington‘s interview with Stoppard called him a “playwright of ideas” and pointed out that “his plays sometimes suggest showbiz razzle-dazzle underscored by hours in a library.” In other words, it is not necessary to understand the full force of Stoppard’s ingenuity, nor to pick up all the subtle references left dangling in his word in to enjoy his plays on their own merits, since they can be appreciated at several different levels.

Nonetheless, Travesties, Stoppard’s second full-length play, was first performed in 1974 and in revival loses nothing for a good shake-up in the hands of a younger protege, the formidably talented Patrick Marber. As a director, playwright, thinker and entertainer, Marber has proved himself to be fashioned from the same combustible material as Stoppard, possibly why a collaboration over a revival seemed inevitable, since the contents are way too good to consign to history.

In this case the mix includes selections from The Importance Of Being Earnest, Joyce’s Ulysses, Marxist-Leninist theory, revolutionary art, a touch of real-life history (Henry Carr, an embassy official, sued Joyce for the cost of a pair of trousers used in a production of TIOBE.) The facts are filtered unreliably through the mind of the aged and senile Carr in the form of an intellectual pantomime – a kaleidoscopic farce wrought through creative jumbling of people and events that could not have happened concurrently. Indeed, scenes are repeated through multiple time slips as Carr’s rambling mind briefly tames its hallucinatory fantasies and focuses on the narrative.

However, it is the voice of the playwright that speaks loudest, including much elaborate word-play (and linguistic jokes you would not get first time), limericks, song and dance routines, through to sections lifted almost verbatim from TIOBE, the writings of Lenin and Joyce’s Ulysses.

There are similarities with other works (characters breaking into song and some of the satirical wit reminds me of Dario Fo‘s delightful and equally biting Accidental Death Of An Anarchist), though Stoppard’s own views are very different from Fo’s Communist tendencies. For example, Stoppard uses Carr as a mouthpiece for gentle mockery of Lenin, but then coming from a country ravaged by the Soviet Communist era that is not surprising.

What we have is a fine pedigree and the expectation of something special, a buzz in the air if you will; I for one was not disappointed, but that will come in due course. Let’s start with the set: the first thing you spot are an array of papers – documents – built into the flooring, giving the appearance of an explosion in a records office. At the centre is a tall workstation reminiscent of a Dickensian head clerk’s desk – or for that matter the imposing presence of an old fashioned courtroom; one almost expects the hanging judge to appear.

The quadrilateral set has in the foreground Henry Carr’s living room table and on the far wall a piano (which he briefly plays), surrounded by tall panelled sections incorporating doors and hidden exits portraying the library, including a path round the back of the set that enables the audience seated on high to see what goes on beyond the immediate stage, where conventional theatres and sets offer a much flatter perspective, giving the audience an unusually three dimensional performance, literally as well as metaphorically.

This is an accurate and orthodox interpretation of Stoppard’s stage directions, and in the process creates something of a labyrinth enabling characters to pop up unexpectedly from various openings – including the base of the desk and panels within the set and doors – in the finest traditions of classic farce.

Of the characters populating this set, the aged Carr makes himself the star attraction. Like Salieri in Amadeus, the character is first shown as a shambling old man at the end of his life, but where Salieri becomes increasingly marooned in his complicit paranoia due to the increasingly ferocious one-sided battle with his deity, Carr turns his own minor role in history into a grandiose celebration of his Wildean wit. Hollander rises to the challenge of lengthy monologues and dazzling jokes timed to the millisecond with charm though possibly understating the self-aggrandisement.

The virtually omnipresent Tom Hollander as Carr is certainly one factor enabling Marber to superglue together the disparate elements of Stoppard’s oeuvre, no mean feat in itself. Hollander has made a career as a finely nuanced character actor rather than a star, being slightly short of stature and without the looks of a matinee idol. His characters are often diffident by nature but of good virtue, the previous exception being loyal but suspicious villain “Corky” Corkoran in the well-reviewed The Night Manager.

Here he is required to extend his range between young and old, nimble and shuffling. In fact, the very epitome of versatility within one role, all the more when spouting a range of tongue-twisters in short order. He is never short of impressive as Carr, less through physical presence than through verbal dexterity. As the old man his volume drops, such that the audience leans forward to capture his every word, and this audience was most certainly held by the words – of which are many (his initial monologue goes on for 4-and-a-half pages.)

Hollander is well served by the ensemble, notably Freddie Fox‘s dashing Tristan Tzara, served up with a good slice of manic energy, such as leaping frog like across stage in the height of his Dadaist anti-art performance. Fox’s reputation is, like that of his father Edward, the lean posh bloke, but then Fox is definitely a chip off the old block – at times he almost looked like The Jackal!

By contrast, Peter McDonald‘s Joyce, aided by Amy Morgan‘s Gwendoline (yes, the Importance character and librarian for these purposes) seems perversely whimsical, embodying the very opposite of Tzara’s confrontational art form by not caring what reaction he invokes. Gwendoline naturally interacts with Clare Foster‘s Cecily, Carr’s niece, notably in a delightfully silly rhyming song-spiel acting out their relationship in TIOBE over tea at Carr’s.

Forbes Masson takes a more introverted approach to Lenin, who cuts a frustrated figure in the days before the October revolution. Indeed, some of his ideas seem half crazed, even to his loyal wife Nadya (Sarah Quist), though Carr is more of an observer than interlocutor in their correspondence, as if he is saying their own words are sufficiently bizarre that he needs add little.

Finally we have Tim Wallers‘ cunningly named manservant, Bennett, cunning because Bennett was the Consul-General to Carr’s minor official – the roles reversed in Carr’s demented version of events. Bennett’s role, amended by multiple time slips, does provide an authoritative history lesson in several guises, depending on whose sympathies he relates at the time, each time in a deadpan voice but going successively off the rails. It takes a brave playwright to play with time in that fashion, and a better one still to get away with it.

All the cast contribute to the razzle-dazzle at various times, and indeed the serious subtext, but together they succeed in delivering Stoppard’s true intent, that of entertainment to send you home thinking. In Travesties, there is enough content to keep you thinking for some considerable while about the nature of art, literature and politics. As with the best plays of this genre, there are many parallels you can make to the pleasant day, so the kindest thing to say is that we never learn the lessons the playwrights, historians and academics have so thoughtfully documented for us.

But then, you could just go home having had your brain stretched slightly and go to sleep with a smile on your face. Clever man, that Stoppard, and that Marber too. Ah, but this production only runs til 29 April, before it too becomes history. Get your tickets while you can!

Oh, and in case you hadn’t guessed, I was dazzled.