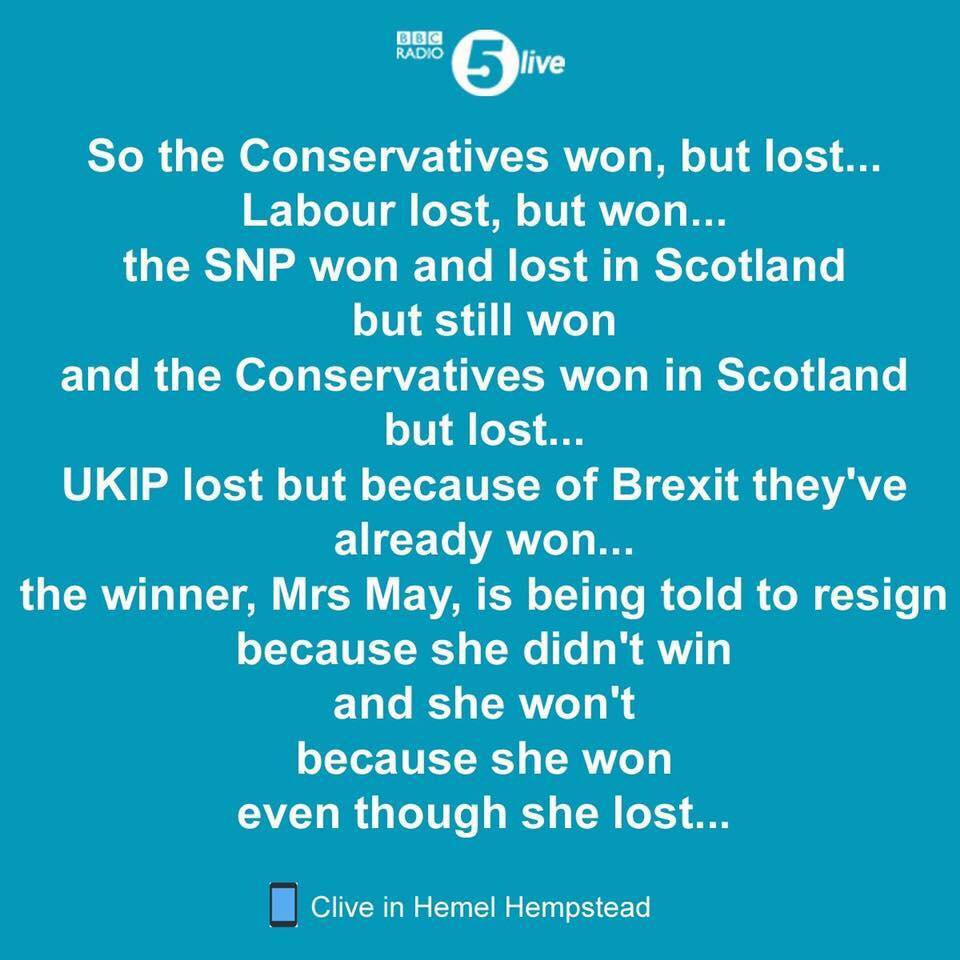

Oh my, what a few days this has been. Our expectations of British politics have, if not been turned upside down, then certainly they have surprised – and that includes the Prime Minister who expected to be handed a majority of at least 50 and possibly 100 or even 150. The landscape has changed in ways we did not anticipate as well as those we did predict:

- The collapse of UKIP was much anticipated, especially since the Brexit referendum left the right-wingers with no axe to grind, and the election of Paul Nuttall as leader confirmed their descent into buffoonery.

- The extent of the SNP’s collapse was less anticipated, though they remain in charge of the Scottish Parliament. Whether that weakens their case for a second indie referendum remains to be seen.

- The ability of Corbyn to defy all the doubters and gain a hung parliament when critics saw him losing to a 100+ majority, even if Labour ended up the smaller party by 56 seats. That they gained over 30, particularly in their own heartland and even in Tory strongholds like Kensington was simply not foreseen or foreseeable.

- The awful election campaign run by May and her team, and her reluctance to be interrogated by media and public alike were simply not predictable beforehand – and leave her, in the words of ex-Chancellor George Osborne, as a “dead woman walking.”

- The failure of Gina Miller‘s campaign to promote tactical voting produced curious results, namely the consolidation of votes for the duopoly of Conservative and Labour parties, the effect, many would say, of First Past The Post as the voting system (see the difference between FPTP and any system of proportional representation here.)

Of course, the final tally of seats mean the agony is prolonged and the next government could well fall as soon as it falls foul of a back bench rebellion. May may find herself resigning or being challenged at any time, so she personally is walking a very fine line while pretending it’s business as usual and the election result was exactly what she expected. Hubris ultimately is its own punishment, though you will find plenty of analysis on how May blew her majority (try this one for size.)

You could easily argue that in practice everybody lost. May was clearly the biggest loser, but Labour failed to take advance to become the biggest party – though it’s a perfectly foreseeable scenario that May is challenged for the Conservative leadership and her replacement calls an election.

Corbyn is clearly banking on momentum carrying him through to the premiership in the event a second election is held in October or next Spring – and the fact that he captured the youth vote is a massive factor in his favour. More than that, Labour finished 792,228 votes behind May’s Conservatives, representing just 0.4% of the popular vote and considerably closer than the margin in seats – all of which leaves the Tory party feeling desperately insecure.

Perhaps the rise of Labour from the dead is the most remarkable story, since nobody had predicted anything other than a crushing Tory win as recently as 6 months ago. But then, Corbyn worked hard on improving his credibility as May destroyed her own. As the Tories blundered and Corbyn’s team focused on social media and winning the youth vote with huge success, and apparently building on success by winning even more popularity since the election result.

In fact, had the right to vote been extended to 16 and 17 year olds, chances are that Labour could have won an outright majority, so no surprise the Conservatives were against it on principle. Never forget that all the key constitutional decisions are governed by the self-interest of parties, and we are much the worse for that.

Meanwhile, May has rightly been accused of poor judgement by the media and her own party, though it is her joint chiefs-of-staff whose heads rolled. But there are plenty of other reasons to suspect May’s judgement, with a few listed below:

1. Timing

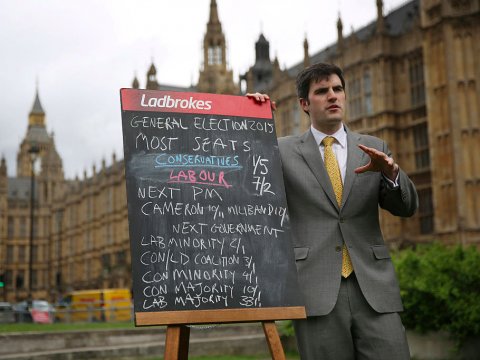

The timing of this election was very strange. May came to power without a final vote, subject of a coronation by her party. You might have thought it sensible to hold an election immediately given her honeymoon period and the fact that Labour were then engaged in a bloody internal wrangle, all the better to avoid Gordon Brown syndrome (he having inherited Labour leadership after the resignation of Tony Blair and choosing not to go to the country for a mandate.) But no, she claimed the 2015 election was a mandate and promised there would not be an early election.

Then she did a total u-turn and called a snap election. Why? Nervousness about the potential legal case against 13 of her MPs for false declaration of election expenses may have contributed, though in practice only one was charged (and he was re-elected in 2017!), though her claim was to gain a bigger mandate than the majority of 5 Cameron somewhat surprisingly won over Ed Miliband’s Labour in 2015.

No doubt about it, May totally misjudged the mood of the country and its view of her first year in charge, as indeed did the pollsters (again.) Yet, had she obtained a parliamentary vote to run an election in June 2016 (another Cameron legacy, the Fixed Term Parliaments Act), she would certainly have won a large majority.

As it was, this election was neither one thing nor another, simply evidence of insecurity and gambling. It coincided with Corbyn having had time to organise an effective campaign, though ultimately it was May’s inexperience that told (see here, repeated at the bottom of this blog.)

2. Brexit

May was a remain campaigner who came to the premiership with a bullish “Brexit means Brexit” stance, and a “hard Brexit” policy that alarmed even many who voted to leave the EU. Leaving the single market in the hope of negotiating some other form of free access to trade with EU countries but without conceding free access to labour. Bearing in mind May as Home Secretary failed to reduce net immigration, it seems her first priority is to do so, and thus appease the right of her party, above all else – though the public knows only too well how much the NHS in particular depends on doctors and nurses from the EU and elsewhere.

In view of Labour’s ambiguity over Brexit (Corbyn was a closet Brexiteer for many years and certainly gave out mixed messages in response to calls from his PLP for clear leadership and an olive branch to the 48% of remain voters), you’d think May would have gone for an easier policy option – bearing in mind that the referendum vote by a slim majority was to leave the EU, not when or how.

If then her aim was to gain a mandate for her “strong and stable leadership” of Brexit, the British public told her resoundingly they had little faith in her policy, and especially the unfeasible promises for a stronger economy that look little more than fiction at this stage, all the more since Trump will be giving no pretty gifts tied up with ribbon (the rumour is that he has postponed his scheduled state visit until the British people like him, which will be never!) Furthermore, May’s administration is increasingly responsible for the contracting out to private companies of NHS Trusts, and nobody will forget the outright lies on the Brexit battlebus declaring that £350m a week allegedly saved from withdrawal of EU membership would go to the NHS – with her Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson leading the chant!

Paradoxically, if she had recognised that Brexit was out of the ordinary political context she could have established the planning and negotiation under a National Unity committee. She could then have included the likes of the very capable Sir Keir Starmer in her negotiating team and gained consensus support from all sides, sidelining the hardliners. The effect would have been to take the sting out of Brexit, encourage experts to contribute and probably to win May the election with a clear majority.

Too late now, of course, and the impact will be felt when either a bad deal is negotiated, or no deal at all; then, the Commons and a good number of her own MPs may vote against, but certainly the British people will protest that we don’t have what was promised. Oh, and for the record no deal means WTO terms, and that means paying tariffs for our trade.

3. “Dementia Tax”

I’ve already discussed this extensively in my analysis of manifesto pledges on health and social care (see here), but this issue demands discussion from a political standpoint. This was allegedly a policy dreamed up by ex-Chiefs of Staff Nick Timothy and Fiona Hill but evidently not given a sanity test by anyone outside May’s coterie of yes-men and women. The problem for her staff is that May does not listen.

The principle that people should have to sell their house to fund 24 hour nursing if they are afflicted by the lottery of long-term degenerative conditions, quite apart from social care to support the elderly living alone, is an anathema to all parties. But the question remains of how you fund care for those who need it, regardless of their assets: through general taxation, which could be a hugely expensive proposition and only benefitting those who need the care. Clearly May’s advisors thought they had come up with a winning wheeze: fund the care during a person’s lifetime but recoup all but £100k max through their estate, but with no upper limit to how much the individual would be charged in respect of their care.

The downside from a Tory standpoint is that this would hit hardest their own supporters who hoped to pass on assets through inheritance, and indeed had hoped the Tory party would abolish inheritance tax altogether. Apparently this did not occur to the May team, which makes this a rare, if not unique example of honesty in a political manifesto.

The impact and widespread furore surrounding this fiasco caught the campaign entirely by surprise, to the extent that May went into an interview a couple of days later to suggest there would be an upper cap – and also mendaciously to suggest this was not a u-turn – but by then the damage was done. You can only put this blunder down to naivity, but there can be little doubt it cost them many votes in constituencies they had every expectation of winning.

May could have devised a much blander and less controversial policy, but then complacency had set in and she never dreamed it possible that the polls talking of the closing gap with Labour might result in a hung parliament. When you take things for granted, you take your eye off the ball.

4. Media relations

No question about it, the most successful leaders have mastered the art of looking good in the media, of coming up with the soundbites that make the headlines. It helps to be young, slim, hirsute, well-dressed and chock full of charisma, though the lack of conventional youth and beauty did not seem to impact Corbyn, who developed his own quiet and effective style of disarming harsh and provocative interrogation.

It is true that there is no requirement for any politician to conduct TV debates, but you ignore them at your peril, even where there is no presidential politics to be conducted. In fact, even where the UK does not directly elect its senior office (other than members of their own constituency and their own party) it is an essential component of the top job that the holder is media-savvy and comes across well.

May is not comfortable under heavy grilling or awkward questions from the general public, and comes across as shifty, defensive and embattled, any more than she is comfortable with facing Corbyn at PMQs. She does not answer questions but repeats her pre-learned mantra, avoids eye contact and looks like she is lying, even when she is not. She is self-conscious and communicates negative messages through her body language. Small wonder then that for the biggest media events she chose to send other people (Amber Rudd and Justine Greening for two different gigs.)

In fact, all her appearances were carefully staged to avoid contact with renegade members of the public who might embarrass her before the cameras. All the clapping, cheering hordes were members of the Tory faithful and therefore only ever likely to feed her slow long-hops.

True, she did some of the TV tests, including a leaders Question Time, the regulation grilling by Jeremy Paxman and a few more, but by then a clear message had been sent to the public that the PM was avoiding contact and thought herself above the rolled-sleeves debating style of yore.

Had she been more combative and more personal (as opposed to the presidential style TV party political broadcasts at the start of the campaign), May may well have brazened out a victory and persuaded more floating voters to stick with Tory. As it was, her strapline of “Strong and stable leadership” provided more than a hollow laugh, since she demonstrated nothing but weak and wobbly leadership through the entire campaign.

5. DUP Dilemmas

The big issue now for May, who is trying to continue as if nothing has happened, is what risks she can now not take, especially in relation to Brexit. She made conciliatory noises to the 1922 Committee by apologising (“I got us into this mess and I will get us out of it” – which convinces nobody) and saying she was there to serve them as long as they wanted her (remember the 1922 Committee thinks it is the kingmaker, and woe betide any leader who goes against the backbenchers’ trade union), but there are many liberties she can not now take, and will certainly be seen as damaged goods to the MPs who lost their seats.

But she has a bigger issue in the potential deal with a vile party whose values are contrary to those of May’s own party, let alone the rest of the UK. The two parties haven’t yet agreed a deal let alone published it. I think it suddenly occurred to the DUP that they are in a strong bargaining position, which could end up as an expensive way to buy 10 votes for some legislation – quite apart from the risk of offending Ulster sensibilities.

May herself is clinging on to power, quite possibly by agreement with the notoriously illiberal DUP, though an alliance with an Ulster party causes many problems in itself, particularly their attitudes towards the LGBT community (they detest homosexuality and think it should be illegal, though there are more openly gay Tory MPs than there are DUP votes to buy), abortion (they think it should be banned and certainly not legalised in Ulster), creationism (they think it should be taught in schools) and climate control (their MPs include at least one who does not believe in global warming.) Suggestions in the press are that the Orangemen also want their annual march to Drumcree church reinstating, which could easily flare into further sectarian violence – which the UK government needs like the proverbial hole in the head.

Oh, and money for Northern Ireland, lots of it in perpetuity. And the sure knowledge that every government action will be scrutinised closely for anything contrary to the DUP protestant ethic and unionist doctrine.

No doubt about it, this deal, if it comes, will be at a heavy price and will cause many headaches down the line, even if it is on a vote-by-vote basis. But there are other things for her to consider: The DUP could not vote on issues impacting other than the UK as a whole or Northern Ireland, a legacy of Cameron’s push to ensure “English votes for English Acts” which May is probably cursing now. It will almost certainly mean she can no longer push through controversial legislation like the Heathrow 3rd runway, which her own party (especially the newly re-elected Zac Goldsmith) would vote against.

But it’s also quite possible May might be hoist by her own Brexit petard: will she walk away on the grounds that “no deal is better than a bad deal”?! Either way, the Queen’s speech is postponed and can only be drafted on vellum when the PM has a clear view of what she will likely be able to get through parliament, so compromises are inevitable.

So now there are many eyes watching and waiting for something to happen. A few possible scenarios may emerge:

- May could of course survive for a full term with DUP support, though not many think it likely.

- She could try to coerce other parties to align with her Conservatives to shore up what will be a wafer-thin Tory/DUP majority, though it’s unlikely any would agree.

- She might call a second election herself spontaneously, which is also thought unlikely after her last disastrous decision.

- She may end up being defeated in the Commons and choose to fall on her sword rather than suffer the indignity of a further challenge.

- There could also be a vote of no confidence in her by Tory MPs, which will leave the PM with nowhere to go.

- A “stalking horse” challenger might be nominated from the back benchers, which will in turn give licence to front benchers to throw their names into the hat.

- Any potential new Tory leader might fancy their chances at the polls too…

- …but then we may all be wrong. Watch this space!

alfway through Britain’s seven-week snap election campaign, some in Theresa May’s team came to the conclusion that they had a problem — the candidate.

alfway through Britain’s seven-week snap election campaign, some in Theresa May’s team came to the conclusion that they had a problem — the candidate.

hile the decision to call a snap election three years before the end of the government’s term came as a surprise to almost everyone in Westminster, May’s co-chief of staff Timothy had pushed for a vote for some time, according to one senior Tory aide close to him. Timothy, a long-standing May ally who was dropped from the party’s list of official candidates by Cameron’s team in 2014, wanted to establish May’s own mandate and led the process of putting together the party’s electoral manifesto.

hile the decision to call a snap election three years before the end of the government’s term came as a surprise to almost everyone in Westminster, May’s co-chief of staff Timothy had pushed for a vote for some time, according to one senior Tory aide close to him. Timothy, a long-standing May ally who was dropped from the party’s list of official candidates by Cameron’s team in 2014, wanted to establish May’s own mandate and led the process of putting together the party’s electoral manifesto.

he campaign had begun so well.

he campaign had begun so well.

n election night, the 12 most senior figures — including Hill, Timothy, Crosby, Messina, Gilbert and Textor — gathered to hear the exit poll in private before filtering back out into the main open-plan room at campaign headquarters where the rest of the staff watched the forecast of a hung parliament in horror.

n election night, the 12 most senior figures — including Hill, Timothy, Crosby, Messina, Gilbert and Textor — gathered to hear the exit poll in private before filtering back out into the main open-plan room at campaign headquarters where the rest of the staff watched the forecast of a hung parliament in horror.