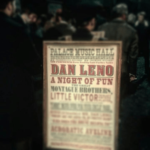

Adapted from the novel by Peter Ackroyd, the man who knows more about London than anyone living, The Limehouse Golem is a true piece of Grand Guignol, encompassing bloody gore, the theatrics of Music Hall and the steady plod of patient detective work to get to the startling truth. This it does with vivid effect through the persona of the legendary George Wild Galvin, aka Dan Leno and his catch phrase:

“Here we are again!”

Granted there are historical distortions here, since the film is set in 1880 but Leno, who was born in 1860, did not start performing in London until 1888, but only the most obsessive historians would scoff.

This notable piece of homage plays as the backdrop to a Victorian detective story worthy of Jack the Ripper, and with no fewer twists and turns. Its claustrophobic, dimly-lit interiors, close-ups of facial expressions, washed out colours, and minute examination of nicely aged documents further the art of the Victorian recreation beyond its usual hackneyed cinematic style. There is the usual collection of pubs, dodgy back streets, fancy women and hansom carriages too, though the effect is splendidly atmospheric and entirely plausible.

I’ll say up front that there is a big twist in the end of this story, which two out of three in my party spotted a long way off, but I don’t think it detracts from the viewing pleasure if you do. The tale, as they say, is in the telling, and in practice it pans out like a Sherlock Holmes tale minus Holmes and Watson but with a slightly more perceptive but ultimately doomed version of Lestrade.

Our principal protagonists are John Kildare (Bill Nighy), the detective inspector allegedly set up to fail in the pursuit of the Limehouse Golem, the latest serial killer to stalk the streets of the East End, and Elizabeth Cree (Olivia Cooke), music hall performer and wife of one of the four suspects (Sam Reid‘s John Cree), on trial for his murder by poison.

That said, this is a fine ensemble cast featuring splendid talents such as Daniel Mays (who I once saw at the Old Vic in The Caretaker), Eddie Marsan, Henry Goodman (as Karl Marx), Morgan Watkins (as George Gissing), and especially the hypnotic Douglas Booth as Leno, who in many ways is the pivotal character, performed with zesty charisma. Personally I love watching Marsan, a true actor’s actor, though each of the players gets a chance to shine and takes it with consummate skill.

It’s also worth pointing out that the role of Kildare was destined to be played by the late Alan Rickman, to whom the film is dedicated. No disrespect to the excellent Nighy, but I think Rickman would have done a brilliant and deceptively laconic job, which I consider his trademark.

By contrast, Nighy claimed to have done no research prior to the filming, In his hands, Kildare is humourless, intense and understated, but passionate in his desire to save Elizabeth from the gallows by proving her husband guilty of being the Limehouse Golem (a reference to a section from a book on Jewish folklore found in the hands of a Rabbi, one of the murderer’s victims, and duly bookmarked with a bloody knife.)

Kildare’s double-act with Mays’ Constable George Flood forms the main source of rumination about the perpetrator of these crimes, particularly when they narrow down the suspects to four gentlemen present in the Reading Room at the British Museum on the day in question, that being when the murderer wrote his notes in a volume of essays by Thomas de Quincy.

However, the true psychology, what makes the plot tick, comes in the dynamics of characters within the Music Hall. Ultimately it is Cooke who delivers the telling blow with a beautifully judged performance arc, from naive to victorious to threatened to noble. In so doing, Cooke’s Elizabeth captures the heart of Kildare, who had previously been thought within the police service as “not the marrying kind” (ie. probably gay, nudge nudge.)

And that’s about it, since any more detail will reveal more spoilers than you need to know. I will say this: if you have any form of fascination with Victoriana or the legendary killers that allegedly stalked the streets, and indeed with the roots of modern theatre (“the smell of the crowd, the roar of the greasepaint”), then Jane Goldman‘s crackling script (soon after I praised her for Kingsman) and the constantly shifting direction of Juan Carlos Medina delivers the goods.

Herein lies another mystery, for nobody seems to know who Juan Carlos Medina might be in reality, though rumour has it the name might be a pseudonym for a much better-known director. Whoever it is, his film is a ripping night out, I’d say. I hope you enjoy it too.