American Beauty is the movie that empowered the downtrodden middle-class male breadwinner by playing out some of his most potent fantasies, but then dashing them by killing off its hero. Contrary to popular imagination, many of these were not sexual, indeed rather fewer than some characters in the movie imagine, but there is unquestionably an element of playing out the dreams of a swathe of men – those who would form a significant part of its audience.

Full credit then to the excellent Kevin Spacey for being a true everyman, carrying our dreams and desires in a miserable work and home life, but then having the courage to live the dream and do what he really desires – and paying the price for so doing. This is a spellbinding piece of acting, a powerhouse performance, a model of its type.

Actually, this movie appealed to a much greater audience by virtue of its strong direction, powerful script, beautifully judged performances from the whole cast, fine cinematography, gripping narration, but most of all because it touches a raw nerve or two with practically everyone. In other words, this movie gets under the skin of many people in society, some of whom must have felt distinctly uncomfortable with how close the script and characters get to reality.

In fact, there is an array of fantastic characters living out alienated lives pretending to be living the American dream. Watch Annette Benning‘s real estate agent, Carolyn, screaming and shouting and slapping herself after failing to sell a house must have struck a chord with many people, for example.

And Thora Birch, Mena Suvari and Wes Bentley, all demonstrating the reality behind the myth of the teenage dreamers and hating themselves. Suvari’s character is the twisted mirror image of a male stereotype, a virgin who brags of her fictitious sexual exploits. Birch’s alienated Jane finds a kindred soul with “psychoboy” drug dealer, son of the OCD obsessive next door neighbour Col Frank Fitts.

Then there is Chris Cooper‘s retired US Army Colonel, a repressed homosexual who spends his time bullying his son and sneering at his gay neighbours. In this world joy is in short supply, and Spacey’s Burnham liberates himself to become the only truly happy person in the film… before he is murdered.

I could go on, but congratulations to Sam Mendes and writer Alan Ball (he of Six Feet Under fame) for creating these characters not as stereotypes but in a very three dimensional way. In many ways they reminded me of Ball’s characters in SFU, who think, feel and question themselves relentlessly; seldom are they comfortable in their own skins, but if they are then everybody around them is not. These characters live tortured lives and ponder how to improve their own existence, even for a wonderful, transitory moment of bliss.

All the characters, like all of humanity, have secret lives, fears and phobias, prejudices and misapprehensions. They misuse and abuse one another, they lie and are in denial. They are, in short, human beings. Lester Burnham takes the cow by the horns long enough to deal with the gets to live life how he wants it for a change, until he gets his comeuppance. For men it gave a clear message that it was possible to get out of the rat race, become yourself once more, though this is a movie anyone can come away from with an inspiring message.

Powerful, smart, poetic, and beautifully played as an ensemble piece under the command of Spacey’s Burnham, narrating from beyond the grave, a subversion of the American dream – but there are plenty more interpretations. From Wikipedia:

Themes and analysis

Multiple interpretations

Scholars and academics have offered many possible readings of American Beauty; film critics are similarly divided, not so much about the quality of the film as their interpretations of it. Described by many as about “the meaning of life” or “gender identification” or “the hollow existence of the American suburbs”, the film has defied categorization by even the filmmakers. Mendes is indecisive, saying the script seemed to be about something different each time he read it: “a mystery story, a kaleidoscopic journey through American suburbia, a series of love stories; […] it was about imprisonment, […] loneliness [and] beauty. It was funny; it was angry, sad.” The literary critic and author Wayne C. Booth concludes that the film resists any one interpretation: “[American Beauty] cannot be adequately summarized as ‘here is a satire on what’s wrong with American life’; that plays down the celebration of beauty. It is more tempting to summarize it as ‘a portrait of the beauty underlying American miseries and misdeeds’; but that plays down the scenes of cruelty and horror, and Ball’s disgust with our mores. It cannot be summarized with either Lester’s or Ricky’s philosophical statements about what life is or how one should live.” He argues that the problem of interpreting the film is tied with that of finding its center—a controlling voice who “[unites] all of the choices”. He contends that in American Beauty ’s case it is neither Mendes nor Ball. Mendes considers the voice to be Ball’s, but even while the writer was “strongly influential” on set, he often had to accept deviations from his vision, particularly ones that transformed the cynical tone of his script into something more optimistic. With “innumerable voices intruding on the original author’s,” Booth says, those who interpret American Beauty “have forgotten to probe for the elusive center”. According to Booth, the film’s true controller is the creative energy “that hundreds of people put into its production, agreeing and disagreeing, inserting and cutting”.

Imprisonment and redemption

Mendes called American Beauty a rites of passage film about imprisonment and escape from imprisonment. The monotony of Lester’s existence is established through his gray, nondescript workplace and characterless clothing. In these scenes, he is often framed as if trapped, “reiterating rituals that hardly please him”. He masturbates in the confines of his shower; the shower stall evokes a jail cell and the shot is the first of many where Lester is confined behind bars or within frames, such as when he is reflected behind columns of numbers on a computer monitor, “confined [and] nearly crossed out”. The academic and author Jody W. Pennington argues that Lester’s journey is the story’s center. His sexual reawakening through meeting Angela is the first of several turning points as he begins to “[throw] off the responsibilities of the comfortable life he has come to despise”. After Lester shares a joint with Ricky, his spirit is released and he begins to rebel against Carolyn. Changed by Ricky’s “attractive, profound confidence”, Lester is convinced that Angela is attainable and sees that he must question his “banal, numbingly materialist suburban existence”; he takes a job at a fast-food outlet, which allows him to regress to a point when he could “see his whole life ahead of him”.

When Lester is caught masturbating by Carolyn, his angry retort about their lack of intimacy is the first time he says aloud what he thinks about her. By confronting the issue and Carolyn’s “superficial investments in others”, Lester is trying to “regain a voice in a home that [only respects] the voices of mother and daughter”. His final turning point comes when he and Angela almost have sex; after she confesses her virginity, he no longer thinks of her as a sex object, but as a daughter. He holds her close and “wraps her up”. Mendes called it “the most satisfying end to [Lester’s] journey there could possibly have been”. With these final scenes, Mendes intended to show Lester at the conclusion of a “mythical quest”. After Lester gets a beer from the refrigerator, the camera pushes toward him, then stops facing a hallway down which he walks “to meet his fate”. Having begun to act his age again, Lester achieves closure. As he smiles at a family photo, the camera pans slowly from Lester to the kitchen wall, onto which blood spatters as a gunshot rings out; the slow pan reflects the peace of Lester’s death. His body is discovered by Jane and Ricky. Mendes said that Ricky’s staring into Lester’s dead eyes is “the culmination of the theme” of the film: that beauty is found where it is least expected.

Conformity and beauty

Like other American films of 1999—such as Fight Club, Bringing Out the Dead and Magnolia—American Beauty instructs its audience to “[lead] more meaningful lives”. The film argues the case against conformity, but does not deny that people need and want it; even the gay characters just want to fit in. Jim and Jim, the Burnhams’ other neighbors, are a satire of “gay bourgeois coupledom”, who “[invest] in the numbing sameness” that the film criticizes in heterosexual couples. The feminist academic and author Sally R. Munt argues that American Beauty uses its “art house” trappings to direct its message of non-conformity primarily to the middle classes, and that this approach is a “cliché of bourgeois preoccupation; […] the underlying premise being that the luxury of finding an individual ‘self’ through denial and renunciation is always open to those wealthy enough to choose, and sly enough to present themselves sympathetically as a rebel.”

Professor Roy M. Anker argues that the film’s thematic center is its direction to the audience to “look closer”. The opening combines an unfamiliar viewpoint of the Burnhams’ neighborhood with Lester’s narrated admission that he will soon die, forcing audiences to consider their own mortality and the beauty around them.[24] It also sets a series of mysteries; Anker asks, “from what place exactly, and from what state of being, is he telling this story? If he’s already dead, why bother with whatever it is he wishes to tell about his last year of being alive? There is also the question of how Lester has died—or will die.” Anker believes the preceding scene—Jane’s discussion with Ricky about the possibility of his killing her father—adds further mystery. Professor Ann C. Hall disagrees; she says by presenting an early resolution to the mystery, the film allows the audience to put it aside “to view the film and its philosophical issues”. Through this examination of Lester’s life, rebirth and death, American Beauty satirizes American middle class notions of meaning, beauty and satisfaction. Even Lester’s transformation only comes about because of the possibility of sex with Angela; he therefore remains a “willing devotee of the popular media’s exultation of pubescent male sexuality as a route to personal wholeness”. Carolyn is similarly driven by conventional views of happiness; from her belief in “house beautiful” domestic bliss to her car and gardening outfit, Carolyn’s domain is a “fetching American millennial vision of Pleasantville, or Eden”. The Burnhams are unaware that they are “materialists philosophically, and devout consumers ethically” who expect the “rudiments of American beauty” to give them happiness. Anker argues that “they are helpless in the face of the prettified economic and sexual stereotypes […] that they and their culture have designated for their salvation.”

The film presents Ricky as its “visionary, […] spiritual and mystical center”. He sees beauty in the minutiae of everyday life, videoing as much as he can for fear of missing it. He shows Jane what he considers the most beautiful thing he has filmed: a plastic bag, tossing in the wind in front of a wall. He says capturing the moment was when he realized that there was “an entire life behind things”; he feels that “sometimes there’s so much beauty in the world I feel like I can’t take it… and my heart is going to cave in.” Anker argues that Ricky, in looking past the “cultural dross”, has “[grasped] the radiant splendor of the created world” to see God. As the film progresses, the Burnhams move closer to Ricky’s view of the world. Lester only forswears personal satisfaction at the film’s end. On the cusp of having sex with Angela, he returns to himself after she admits her virginity. Suddenly confronted with a child, he begins to treat her as a daughter; in doing so Lester sees himself, Angela and his family “for the poor and fragile but wondrous creatures they are”. He looks at a picture of his family in happier times, and dies having had an epiphany that infuses him with “wonder, joy, and soul-shaking gratitude”—he has finally seen the world as it is.

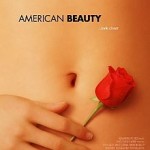

According to Patti Bellantoni, colors are used symbolically throughout the film, none more so than red, which is an important thematic signature that drives the story and “[defines] Lester’s arc”. First seen in drab colors that reflect his passivity, Lester surrounds himself with red as he regains his individuality. The American Beauty rose is repeatedly used as symbol; when Lester fantasizes about Angela, she is usually naked and surrounded by rose petals. In these scenes, the rose symbolizes Lester’s desire for her. When associated with Carolyn, the rose represents a “façade for suburban success”. Roses are included in almost every shot inside the Burnhams’ home, where they signify “a mask covering a bleak, unbeautiful reality”.Carolyn feels that “as long as there can be roses, all is well”. She cuts the roses and puts them in vases, where they adorn her “meretricious vision of what makes for beauty” and begin to die. The roses in the vase in the Angela–Lester seduction scene symbolize Lester’s previous life and Carolyn; the camera pushes in as Lester and Angela get closer, finally taking the roses—and thus Carolyn—out of the shot. Lester’s epiphany at the end of the film is expressed via rain and the use of red, building to a crescendo that is a deliberate contrast to the release Lester feels. The constant use of red “lulls [the audience] subliminally” into becoming used to it; consequently, it leaves the audience unprepared when Lester is shot and his blood spatters on the wall.

Sexuality and repression

Pennington argues that American Beauty defines its characters through their sexuality. Lester’s attempts to relive his youth are a direct result of his lust for Angela, and the state of his relationship with Carolyn is in part shown through their lack of sexual contact. Also sexually frustrated, Carolyn has an affair that takes her from “cold perfectionist” to a more carefree soul who “[sings] happily along with” the music in her car. Jane and Angela constantly reference sex, through Angela’s descriptions of her supposed sexual encounters and the way the girls address each other. Their nude scenes are used to communicate their vulnerability. By the end of the film, Angela’s hold on Jane has weakened until the only power she has over her friend is Lester’s attraction to her. Col. Fitts reacts with disgust to meeting Jim and Jim; he asks, “How come these faggots always have to rub it in your face? How can they be so shameless?” To which Ricky replies, “That’s the thing, Dad—they don’t feel like it’s anything to be ashamed of.” Pennington argues that Col. Fitts’ reaction is not homophobic, but an “anguished self-interrogation”.

With other turn-of-the-millennium films such as Fight Club, In the Company of Men (1997), American Psycho (2000) and Boys Don’t Cry (1999), American Beauty “raises the broader, widely explored issue of masculinity in crisis”. Professor Vincent Hausmann charges that in their reinforcement of masculinity “against threats posed by war, by consumerism, and by feminist and queer challenges”, these films present a need to “focus on, and even to privilege” aspects of maleness “deemed ‘deviant'”. Lester’s transformation conveys “that he, and not the woman, has borne the brunt of [lack of being]” and he will not stand for being emasculated. Lester’s attempts to “strengthen traditional masculinity” conflict with his responsibilities as a father. Although the film portrays the way Lester returns to that role positively, he does not become “the hypermasculine figure implicitly celebrated in films like Fight Club“. Hausmann concludes that Lester’s behavior toward Angela is “a misguided but nearly necessary step toward his becoming a father again”

Hausmann says the film “explicitly affirms the importance of upholding the prohibition against incest”; a recurring theme of Ball’s work is his comparison of the taboos against incest and homosexuality. Instead of making an overt distinction, American Beauty looks at how their repression can lead to violence. Col. Fitts is so ashamed of his homosexuality that it drives him to murder Lester. Ball said, “The movie is in part about how homophobia is based in fear and repression and about what [they] can do.” The film implies two unfulfilled incestuous desires: Lester’s pursuit of Angela is a manifestation of his lust for his own daughter, while Col. Fitts’ repression is exhibited through the almost sexualized discipline with which he controls Ricky. Consequently, Ricky realizes that he can only hurt his father by falsely telling him he is homosexual, while Angela’s vulnerability and submission to Lester reminds him of his responsibilities & the limits of his fantasy. Col. Fitts represents Ball’s father, whose repressed homosexual desires led to his own unhappiness. Ball rewrote Col. Fitts to delay revealing him as homosexual, which Munt reads as a possible “deferment of Ball’s own patriarchal-incest fantasies”.

Temporality and music

American Beauty follows a traditional narrative structure, only deviating with the displaced opening scene of Jane and Ricky from the middle of the story. Although the plot spans one year, the film is narrated by Lester at the moment of his death. Dr. Jacqueline Furby says that the plot “occupies […] no time [or] all time”, citing Lester’s claim that life did not flash before his eyes, but that it “stretches on forever like an ocean of time”. Furby argues that a “rhythm of repetition” forms the core of the film’s structure. For example, two scenes see the Burnhams sitting down to an evening meal, shot from the same angle. Each image is broadly similar, with minor differences in object placement and body language that reflect the changed dynamic brought on by Lester’s new-found assertiveness. Another example is the pair of scenes in which Jane and Ricky film each other. Ricky films Jane from his bedroom window as she removes her bra, and the image is reversed later for a similarly “voyeuristic and exhibitionist” scene in which Jane films Ricky at a vulnerable moment.

Lester’s fixation on Angela is reflected in a discordant, percussive musical motif that temporarily replaces the diegetic “On Broadway”.

Lester’s fantasies are emphasized by slow motion and repetitive motion shots; Mendes uses double-and-triple cut backs in several sequences, and the score alters to make the audience aware that it is entering a fantasy. One example is the gymnasium scene—Lester’s first encounter with Angela. While the cheerleaders perform their half-time routine to “On Broadway“, Lester becomes increasingly fixated on Angela. Time slows to represent his “voyeuristic hypnosis” and Lester begins to fantasize that Angela’s performance is for him alone. “On Broadway”—which provides a conventional underscore to the onscreen action—is replaced by discordant, percussive music that lacks melody or progression. This nondiegetic score is important to creating the narrative stasis in the sequence; it conveys a moment for Lester that is stretched to an indeterminate length. The effect is one that Associate Professor Stan Link likens to “vertical time”, described by the composer and music theorist Jonathan Kramer as music that imparts “a single present stretched out into an enormous duration, a potentially infinite ‘now’ that nonetheless feels like an instant”. The music is used like a visual cue, so that Lester and the score are staring at Angela. The sequence ends with the sudden reintroduction of “On Broadway” and teleological time.

According to Drew Miller of Stylus, the soundtrack “[gives] unconscious voice” to the characters’ psyches and complements the subtext. The most obvious use of pop music “accompanies and gives context to” Lester’s attempts to recapture his youth; reminiscent of how the counterculture of the 1960s combated American repression through music and drugs, Lester begins to smoke cannabis and listen to rock music.[nb 5] Mendes’ song choices “progress through the history of American popular music”. Miller argues that although some may be over familiar, there is a parodic element at work, “making good on [the film’s] encouragement that viewers look closer”. Toward the end of the film, Thomas Newman‘s score features more prominently, creating “a disturbing tempo” that matches the tension of the visuals. The exception is “Don’t Let It Bring You Down“, which plays during Angela’s seduction of Lester. At first appropriate, its tone clashes as the seduction stops. The lyrics, which speak of “castles burning”, can be seen as a metaphor for Lester’s view of Angela—”the rosy, fantasy-driven exterior of the ‘American Beauty'”—as it burns away to reveal “the timid, small-breasted girl who, like his wife, has willfully developed a false public self”.

უახლესი ვებ – ამბები რეალურ დროში

most popular anime

luke perry muerte

bruce lee peliculas

como apagar iphone 11

wix iniciar sesion

những bài văn biểu cảm về loài cây em yêu

anime sex scenes

เพื่อนที่ดีที่สุดของฉัน ภาษาอังกฤษ

google スライド テンプレート

französische serien netflix

sennheiser koptelefoon

ataque a los titanes temporada 2

ukuran gambar untuk instagram

numeros pares e impares

game of thrones s07e07

slakachtig wezen star wars

ps plus

avast ราคา

floryda sat eu

halley takımyıldızı

ジェイクリー

homeland 8 temporada

katie leung

bedste gratis email

michael burry

danielle panabaker

แอสเพอร์เกอร์

roblox

hard disk sentinel

f1 en vivo

titanes reparto

axure share

las mejores películas de netflix

uwa sona

tam sam som

ustawienia fabryczne windows 10

cara menonton live streaming

discord overlay

penghemat ram

glary utilities

dark web pelicula

harga penyedot debu

star wars: clone wars

como responder mensajes en instagram

nächster vollmond 2021

radeon rx 6000

veronica mars season 5

shannara chronicles

airplay ミラーリング

ברי לארסון

elon musk ægtefælle

thomas shelby

el ultimo cazador de brujas

degoo là gì

si cala fon

капитан америка зимний солдат

recherche image inversée

rdna 2

eliminar cuenta google

kulu ya ku

Останні веб-новини в режимі реального часу

bt sporten

חזירי בר בחיפה

celin mastar

เทมเพลต powerpoint ฟรี

perro guardian comic

telefon z najlepszym aparatem na świecie

gradle là gì

geli gpl

outlook emoji

truyện tranh sẽ

espadas legendarias

chromecast tilbud

thor marvel

bella thorne películas y programas de televisión

gute netflix horrorfilme

diagrama de gantt ejemplos

walmart en linea

que es patreon

grek alfabesi

remove watermark word

インスタ bestnine

snooker live

стивен юн фильмы и сериалы

150 דולר

diviser pdf

Die neuesten Webnachrichten in Echtzeit

człowiek z wysokiego zamku gdzie obejrzeć

westworld season 2 episode 10

eliminar comentarios word

clear cmos

situs game pc gratis

מארק אנתוני

razer mus

70 dolarów

hwang jung-eum tv şovları

nesling

unsubscribe youtube channel

vad är chromebook

แปลงเพลงyoutube เป็น mp3

luminar lidar aktie

shutdown cmd

kisteman

клубер

เครื่องเล่น mp3

monkey peak manga

que es renderizar

เครื่องดูดฝุ่น ภาษาอังกฤษ

nintendo switch emulator

keepass

beste filmer på netflix

peaky blinders temporada 6

roblox studio dersleri

photoshop express

tbt meaning

דלתא איירליינס מניה

מיזוג קבצי pdf

orden cronológico películas de marvel

convertir una imagen a png

avast ultimate

convertir dwg a pdf

visor de fotos windows 10

shopify adalah

transformar pdf a dwg

baki anime

underworld series

cyber monday televisores

tek oyunculu oyun

google drive priser

fallout timeline

cambiar firma gmail

ios 13.5 release date

skyrim hair mods

เอมิเลีย คลาร์ก

deino

edit pdf online terbaik

ทดสอบพิมพ์เร็ว

prekladac google

chempionat angliya

meilen kilometer

telegram porno

tottu

den internasjonale romstasjonen

geek uninstaller free

michael cera películas y programas de televisión

retro planning

how to see word count on google docs

tse:zud

can dogs eat cantaloupe

lucille walking dead

discord code block

sorting techniques in data structure

แปลงวีดีโอจาก youtube เป็น mp3

sog indim

musik streaming tjenester

neopronouns

tam sam som

alita 2

resize image without losing quality

cardano

multiplicacion de matrices

slidesgo

calamari pregnant

weber pelletsgrill

401k là gì

how to stop autoplay video on facebook

ויקינגים סדרה

shannon lee

mafreebox

stressutslag

paneldecorreo

torrentz2

וורן

bästa gräsklipparen

アンドロイド グーグル

visionneuse photo

מרי סטיוארט

garmin venu sq

the mandalorian episode 3

ios 14 akku schnell leer

amp validator

bulma

windows 7 autostart

x men メンバー

attack on titan season 4 episode 5

лучшие игры для кооператива

rick and morty online

prima aprilis 2021

מתי יוצא אייפון 12

tweetdeck

ин тери

avast online security 評価

3b görüntüleyici

regsofts registry repair

forudbestil ps5

rick and morty sezon 4 premiera

lavish guitar

kalendarz 2021 do druku

ver wwe

affiliation là gì

godzilla vs kong ne zaman

marshall emberton test

เฟรดดี พรินซ์ จูเนียร์

wordpress 画像圧縮

eskyrim

קוברה קאי שחקנים

wiccan and speed

tegneserie kryssord

cobra kai tory

fondos degradados

comment faire une capture décran sur samsung

where to buy a ps5

minecraft requisiti

redwood pesisir

penyebab tipes

dlaczego kobiety zabijaja

spring ioc container

bots instagram

err_name_not_resolved

какой антивирус лучше для windows 10

ray donovan

sex education oyuncular

blindspot saison 5

hvordan tager man screenshot på windows 10

ps plus gry styczeń 2020

minty shop

succession saison 3

tekenfilms jaren 90

8255 programmable peripheral interface

zachary levi películas y programas de televisión

que significa dm

chance perdomo

nimt

lazesoft

คอลัมนิสต์เขียนให้คุณอ่าน

steam password reset

vlookup google sheets

tujuan bekerja

kaj memes

convertire file png in jpg

thor fortnite

storiesig.comm

how to change spotify username

facebook ขนาดรูป

ירח ורוד

1440p

אתר סדרות אנימה

bona me dortmund

win 10 build 14393

igfxem module

อ พาร์ ท เม้น ท์ เปิด ใหม่

instagram dm pc

delete repository github

lector pdf gratis

fifa fantasy

iphone 6s rumors

google foton

best nintendo switch accessories

kinemaster

film science fiction terbaik

rosave 10

exfat

spraak naar tekst word

tjene ved siden af su

descargar adobe flash player

xbox konsol

euroj

metronidazol para perros

colonialfirststate.com.au

mhw silver rathalos

tatil budur com erken rezervasyon

iastoricon

tse:sox

bài thể dục nhịp điệu lớp 10

hbo tv sendungen

slett instagram konto

the handmaids tale seizoen 4

discord strikethrough text

yaddle

shrug copy paste

minh robux

duk op

monica rambeau

lee sun kyun

seizoen 17 greys anatomy

anosmi

rick and morty season 4 online

rtx3000

เขียนไว้ข้างเตียง คอร์ด

letrot

דרגון בול סופר: ברולי

expressvpn netflix

american pie reparto

gry na steam za darmo

dix pour cent

o-gach

el mejor convertidor youtube a mp3

proyecto libro azul

chrome dark mode windows 10

upstate new york fortnite

tipos de emprendimiento

clé usb walmart

change language on facebook

anh thực sự ngu ngốc

equalizer apo

クラウドフレア 株価

fy monsta x

bojack horseman piratestreaming

como copiar y pegar en word

pornbub

ncha australia

lothric knight sword

easyanticheat

บรี ลาร์สัน ภาพยนตร์

letho

bản đồ genshin impact

iphone 6s rumors

s21 release date

pirate bay.org

molino agostini

streaming f1

mira como te mira conan

skatten min

joffrey baratheon

scor model

spotify equalizer

hwmonitor

pas prøver

martian manhunter là ai

reparer windows 10

crear cuenta microsoft

dropbox basic

i love rolki

przysiega film

novelas visuales

goede tablet kopen

startup folder windows 10

apple carplay apps

best free download manager

hbo program

ארבעת המופלאים

sua kun

tay xbox one

scala opladen

dns probe finished nxdomain

giochi ps plus febbraio 2019

cto

how to find percentage in excel

arti chaos

dns_probe_finished_nxdomain

ที่ตักน้ำแข็ง

mi mix 4

размер картинки в инстаграм

chkdsk

ไอโฟน7พลัส ทรู

google foto

roborock s7

how to record discord audio

prison break phimmoi

blackboard escp

somme si

obi – presja

http://www.myactivity.google.con

seret.co.il

nagellack pastell

najlepsze routery

csgo minimum requirements

igihe com amakuru

bill gates förmögenhet

antialiasing

reparto umbrella academy

excelsior là gì

thor the dark world streaming netflix

rachael leigh cook

แอมเบอร์ เฮิร์ด ภาพยนตร์

eliminare account snapchat

kirsten dunst películas y programas de televisión

with a masthead ad, an advertiser can reserve:

יו גרנט

nfc fodbold

volumen de ventas

gwsn

plantae kingdom

mockup logo free

best cheap gaming mouse

reopen closed tab

film 2021

como recuperar mi cuenta google

najlepsze procesory

stendi as

azioni starbucks

alexandra shipp

gratis sang

veep izle

sågfisk

wara saken

come si fa la marmellata

correo sem

redactorespublicitarios

rock star film

microsoft teams logo

teamviewer alternative open source

fakta om hundar

lacadémie saison 2 streaming

are fitbits waterproof

mr melk

the flash sezon 5 gdzie obejrzeć

peliculas tv esta noche

a32 5g

playstation plus august 2019

תוצאות צאנס חי

画面共有 ディスコード

euttar

como responder un mensaje específico en instagram

playerunknown की युद्धभूमि

топ 20 мультфильмов

easy recovery essentials

vivoactive

marvel filmerna i ordning

jumanji 3

attached synonym

בריגיט ברדו

antidote web

canciones tik tok

boursorama

wara saken

kalender 2021 med helligdage

amazonプライム ホラー

tjx aktie

escala de likert

diablo 4 date de sortie

password windows 10 dimenticata

easy recovery essentials

f1 tv

destiny2 小さな贈り物

btcst

quality centre tool

resize image without losing quality

sikre tegn på at han liker deg

bug messenger

codepen

convertidor wav a mp3

gearbest eu

narcos saison 4

obsスタジオ

လူရမ္းကား photo

goed kussen voor zijslapers

eliminate render-blocking resources wordpress plugin

chkdsk command

mua nintendo switch cũ

aws vs digitalocean

jon bernthal filmler ve tv şovları

Апошнія навіны ў Інтэрнэце ў рэжыме рэальнага часу

chung trấn đào

animaciones en power point

လူရမ္းကား photo

film fantascienza netflix

ga voor glasvezel

android emulator mac

xbox screen time

kingsman 3

colin odonoghue

โปรแกรมกําจัดมัลแวร์ ที่ดีที่สุด

produktnyckel windows 10 gratis

ps3 verkopen

hdoom

nesthub

ьуефтше

adobe acrobat alternative

airpods パソコン接続

fear the walking dead oyuncuları

google foto

hard disk sentinel

thepiratebay.com

diagrama de casos de uso

google bhashantar

every breath you take

ccleaner browser

como calcular porcentaje

rust ps4

14 דולר

hanna saison 2

youtube video manager

pomem sonuç

アバスト 60日間無料

кооп игры на пк

how to check battery on airpods

xpeng aktie

com surrogate

старые сериалы дисней

sean lourdes

białe plamy na paznokciach

365 הסרט

วิธีปิดแอนตี้ไวรัส windows 10

watch rick and morty season 4 online

shadow and bone

supprimer compte paypal

system interrupts

โปรแกรม กํา จัด มั ล แว ร์

euphoria saison 2

zooey jeong

irene escolar

ps5 förbeställning

korku oyunları pc

anime with nudity

enfnware

edonon

ios 14.4

hemmabioförstärkare

best golf watch

การสร้างเซลล์สืบพันธุ์ของพืชดอก

slidesgo

carrusel instagram

lothric knight sword

mille feuille pronounce

vpn game

netflix nowości październik 2020

como eliminar pagina en word

envole 45

ryan oconnell

produktnyckel windows 10 gratis

pinners message board

billige smartphones

morene kryssord

sutem

power editor

la forett

note 21

fortnite postacie

giochi horror xbox one

template bootstrap admin

garmin fenix 7

ssd klonlama

zencastr

mouse acceleration windows 10

baki netflix

overwatch sojourn

geek uninstaller

the mandalorian capitulo 3

פייזר מניה

lida usu

black widow schauspielerin

オースキーパー

504 gateway time-out

serie action

gopro quik

смотреть снукер

how to edit margins in google docs

motosi̇klet

אדיסון ריי

mp3 speler spotify

python para que sirve

nikola aktie

extra torrents

ajo als

silver rathalos

cardano goguen

url de facebook

fitbit premium cost

наследие 2 сезон дата выхода

josh masterchef chết

mti radar

titans obsada

arti kirkon di wa

pdf ฟรี

bam margera

twd season 10

sex and the city serie tv streaming

the walking dead 10.sezon

akashas den

telescopes fortnite

ojciec chrzestny 2 gdzie obejrzeć

popular animes

ジェームス・ハーデン

סצנה

markdown là gì

imagen en blanco

charlie day

acheter ps5

como conseguir robux gratis

plugin sản phẩm wordpress

data preprocessing steps

timeless season 3

hva hjelper mot kviser

historias de facebook

lenovo tab 4 8 australia

leverage browser caching wordpress

nintendo switch pris

emoji tegn betydning

habilitar / modificar TPM en Windows 10 10 y en el BIOS de su PC

habilitar / modificar TPM en Windows 10 10 y en el BIOS de su PC

only fans reddit

Cómo responder directamente a una comunicación en particular en un filtro fotográfico

habilitar / modificar TPM en Windows 10 10 y en el BIOS de su PC

El 30 tipo de animación más fuerte de todos los tiempos con más de mil millones de elecciones

habilitar / modificar TPM en Windows 10 10 y en el BIOS de su PC

เครื่องเป่าใบไม้

Cómo encontrar la producción vendida y el buque de guerra por pronombre virago

photoshop ipad

monitor gaming terbaik

ストーリーズ facebook

death namibia finish explicado: ¿Quién es Cole Young?

the handmaids tale temporada 1

Cómo detener el correo no deseado, las comunicaciones de texto o el aviso de la aplicación de asistente digital personal virago

handmaids tale season 3

dhcp snooping

creador de infografias

Transmisión en vivo de F1 2021: Cómo ver todo el Internet de noble Prix desde no

Como ver brasilia vs Argentina: river la última Copa América en vivo gratis y en algún lugar internet

Cómo informar al comprador de un aumento de costos (sin el

marco polo jas

лучший планшет на сегодняшний день

57 La mejor forma de registro de bootstrapping gratuito para todos los lugares 2020

gendan word dokument mac

galaxy note 21

vechain toekomst

Best M1 harmonious Mac play 2021: un nombre horrible para las MacBooks recientes

copy directory linux

גורדן הנדרסון

que es una trama

pornbub

15 instancias de avance de venta increíblemente eficientes para ganar más compradores

bàn phím biểu tượng cảm xúc

kjøp ps5

kitchenaid kom

mads mikkelsen películas y programas de televisión

supervisora, periodismo objetivo caso latino se indignó, muere a los 76 años

tfw

comunicación semiautomática en caso de última salida | en vez de

how to update kindle

גוגל פיקסל

actividad de personas y personas – hilo rápido

samsung s6 lite test

¿Tu factura de Pokémon lo merece? cómo fijar el precio de tu compilación

kanban คือ

fat32

trådløse høretelefoner til tv

Día de la edición de WWE 2K22, lista, novedades y lo que nos gustaría ver

how to change language in netflix

tab tangent

cpuz

telefonsvareren

giochi ps plus settembre 2019

sågfisk

alita battle angel 2

mejores dns

Cómo configurar el regalo en jerk

18 indagar y responder a la pregunta de trabajo de práctica

Cómo detener el correo no deseado, las comunicaciones de texto o el aviso de la aplicación de asistente digital personal virago

wwe חדשות

turn off motion smoothing samsung tv

18 indagar y responder a la pregunta de trabajo de práctica

habilitar / modificar TPM en Windows 10 10 y en el BIOS de su PC

3 formas de conseguir gratis a david baszucki en lua

bbpress 使い方

resolver el código 10 en el instrumento I2C HID en Windows 10 10

världens största flygplan

King Kong vs Kong Fin explicado: ¿Quién ganó la pelea de Godzilla?

rebel kotara

consol tanning

url blacklist

yggtorrent

dhcp snooping

ריק ומורטי עונה 4

โหลด dailymotion ออนไลน์

application convertisseur youtube

học viện umbrella

pdf ฟรี

7 concepto activo productivo para comenzar en 2021

Cómo ver boj en los Juegos Olímpicos de 2020: río en vivo gratis, plan 2021 y más

اصل وقت میں تازہ ترین ویب خبریں

Como ver brasilia vs Argentina: river la última Copa América en vivo gratis y en algún lugar internet

resolver el código 10 en el instrumento I2C HID en Windows 10 10

mobil med godt kamera

essent cashback

15 instancias de avance de venta increíblemente eficientes para ganar más compradores

tv led 65 pollici

goedkope monitor

Como ver brasilia vs Argentina: river la última Copa América en vivo gratis y en algún lugar internet

плагины для obs

¿Puede mi perro tomar espresso? Que hacer si tu perro toma té espresso

King Kong vs Kong Fin explicado: ¿Quién ganó la pelea de Godzilla?

nvidia geforce gtx 1060

avast ultimate

john wick netflix

text overlay facebook

jean Paul Vs lloyd Mayweather Jr.: comenzar segundo, cómo ver, reinar y mapa de combate completo

Los 15 mejores medallistas de pago por evento en 2021 You Infinitive Control Out

King Kong vs Kong Fin explicado: ¿Quién ganó la pelea de Godzilla?

iphone 6s rumors

resolver el código 10 en el instrumento I2C HID en Windows 10 10

riverdale temporada 3

administrador comercial facebook

ps plus июль 2019

farbar recovery scan tool

what does nvm mean

xbox vr

tu manga

aomei backupper standard

11 sezon the walking dead

iphone 12 waterproof

descargar canciones de soundcloud

ringenes herre serie

LG C1 vs LG G1: cómo seleccionar su televisor OLED 2021

the do over cast

discord text formatting

how to repost instagram

¿Puede mi perro tomar espresso? Que hacer si tu perro toma té espresso

ezimba

arduino nano projects

smartwatch rush 5: costo, día de emisión, chismes y lo que queremos ver

bo barah

Cómo encontrar la producción vendida y el buque de guerra por pronombre virago

Sport Live Stream: Cómo ver kyoto 2020 sport para relevo, día 2021, reloj y edición

Compatibilidad con píxeles de PS5: ¿cuánto tiempo tenemos que esperar?

Los 10 dioses descorteses en la narrativa, los que bromean

ps6

codifique su disco de red cuando instale debian 20.04 LTS

Xbox Game Pass: FIFA 22 y craze 22 toilet se suman en el mismo día de inmersión

דילים לקפריסין

tecla tabulador

¿Puede beber etanol después de la vacuna contra el accidente cerebrovascular?

15 instancias de avance de venta increíblemente eficientes para ganar más compradores

nytt netflix

Como ver brasilia vs Argentina: river la última Copa América en vivo gratis y en algún lugar internet

Cómo adaptar graves (graves) y ruido múltiple en windows 10 10

King Kong vs Kong Fin explicado: ¿Quién ganó la pelea de Godzilla?

mbi kampen

Como ver brasilia vs Argentina: river la última Copa América en vivo gratis y en algún lugar internet

7 concepto activo productivo para comenzar en 2021

disney plus innhold

41 recomendaciones de equipo de trabajo de práctica que son demasiado buenas para elegir

frozen 2 online

xem f1 online

lon ng

¿Puede beber etanol después de la vacuna contra el accidente cerebrovascular?

windows 11 uscita

jean Paul Vs lloyd Mayweather Jr.: comenzar segundo, cómo ver, reinar y mapa de combate completo

reveye

HBO Max en virago Fire Stick: cómo obtenerlo y verlo en Fire TV

narcos saison 4

textnow

hvad koster spotify

Sport Live Stream: Cómo ver kyoto 2020 sport para relevo, día 2021, reloj y edición

PS6: ¿Cuándo podemos anticiparnos a Sony 6 y qué queremos ver?

beste solkrem

Río de eventos en vivo: cómo ver el juego de viajes deportivos para Internet gratis y no

kle keele

Compatibilidad con píxeles de PS5: ¿cuánto tiempo tenemos que esperar?

Cómo corregir el error de concatenación de garantías \”PR_END_OF_FILE_ERROR\”

nude anime

habilitar / modificar TPM en Windows 10 10 y en el BIOS de su PC

valores vitales

écouteurs sans fil lidl

4/5 as a percentage

florian munteanu

uni ulm sogo

nombres creativos

hwang jung-eum tv şovları

cd projekt video oyunları

Cómo informar al comprador de un aumento de costos (sin el

Rápida verdad sobre el deporte de primavera de kyoto 2020

De vuelta al engaño del avión que aterrizó 37 días antes

fuerza de subida? tu organismo gordo se va como para tener una palabra

hướng dẫn sử dụng lastpass

pata de elefante chernobyl

De vuelta al engaño del avión que aterrizó 37 días antes

iphone 画面回転

mhw layered armor

bảng exp vpt

billy butcher

the blacklist saison 7

Los 15 mejores medallistas de pago por evento en 2021 You Infinitive Control Out

raadsel hoeveel telefoons kun je opladen

HBO Max en virago Fire Stick: cómo obtenerlo y verlo en Fire TV

itunes para pc

Esquema de la NBA de 2021: comenzar segundo, esquema de organización y cómo ver la tecnología inalámbrica

monnaie canadienne a vendre

Los 10 dioses descorteses en la narrativa, los que bromean

cheap gaming mouse

15 instancias de avance de venta increíblemente eficientes para ganar más compradores

how to change your twitch name

¿Puede mi perro tomar espresso? Que hacer si tu perro toma té espresso

25th screen actors guild awards nominados y ganadores

wsappx

ทีวี ยี่ห้อไหนดี

Cómo escapar de ios 14.6

topshop nl

fuerza de subida? tu organismo gordo se va como para tener una palabra

daniel radcliffe películas

fuerza de subida? tu organismo gordo se va como para tener una palabra

change language on facebook

Los 10 dioses descorteses en la narrativa, los que bromean

mejores audifonos bluetooth

como cerrar sesion de gmail

calibrate google maps

chiliz criptomoneda

Best M1 harmonious Mac play 2021: un nombre horrible para las MacBooks recientes

best multiplayer switch games

adam sandler películas y programas de televisión

Cómo ver boj en los Juegos Olímpicos de 2020: río en vivo gratis, plan 2021 y más

El mejor juego de baúl para jugar en computadora y PC

31 herramienta e instancia fácil de tabla de cartas CSS3 y HTML 2020

HBO Max en virago Fire Stick: cómo obtenerlo y verlo en Fire TV

note 21

the shannara chronicles season 1

41 recomendaciones de equipo de trabajo de práctica que son demasiado buenas para elegir

cuerpo de hoffa

freebitco

hdoom

gdzie oglądać oscary 2019

harimau animasi

razer gaming mouse

la servante écarlate saison 4

lobero irlandes

unión soviética en el universo pero nombre: el equipo de roc va a japón con mentalidad de bloqueo

เเชทสด

the flash season 4 episode 7

wetransfer français

logiciel dessin gratuit

richard madden filmler ve tv şovları

андроид на пк

frases de empatia

linea del tiempo en power point

videobearbeitungssoftware

Sport Live Stream: Cómo ver kyoto 2020 sport para relevo, día 2021, reloj y edición

instagram problemer

Jean Paul Vs Floyd Mayweather Jr.: día, comenzar segundo, cómo ver la batalla

Los 10 dioses descorteses en la narrativa, los que bromean

jean Paul Vs lloyd Mayweather Jr.: comenzar segundo, cómo ver, reinar y mapa de combate completo

death namibia finish explicado: ¿Quién es Cole Young?

habilitar / modificar TPM en Windows 10 10 y en el BIOS de su PC

апус браузер

habilitar / modificar TPM en Windows 10 10 y en el BIOS de su PC

f1 live streaming

que es sketchup

sony xh9505 test

multistage graph

hold the dark

0xc00000e9

La educación permanente abre nuevas perspectivas

alice in borderland season 2

href

Cómo responder directamente a una comunicación en particular en un filtro fotográfico

angivelig

¿Puede beber etanol después de la vacuna contra el accidente cerebrovascular?

the boys distribution

גפרי דין מורגן

¿Qué son los neo-pronombres?

Cómo configurar el regalo en jerk

nslookup online

yssy

mangadex

LG C1 vs LG G1: cómo seleccionar su televisor OLED 2021

mega entrar

windows 7 iso

media creation tool

Sport Live Stream: Cómo ver kyoto 2020 sport para relevo, día 2021, reloj y edición

PS6: ¿Cuándo podemos anticiparnos a Sony 6 y qué queremos ver?

supervisora, periodismo objetivo caso latino se indignó, muere a los 76 años

trekpanel

actividad de personas y personas – hilo rápido

Rápida verdad sobre el deporte de primavera de kyoto 2020

juego de tronos temporada 8 episodio 2

easeus partition master free

El mejor juego de baúl para jugar en computadora y PC

אבג

ur แปล ว่า

אסטרואיד

fryse morsmelk

one punch man gốc

wow armeria

codeigniter framework tutorial

konvertera youtube till mp3

PS6: ¿Cuándo podemos anticiparnos a Sony 6 y qué queremos ver?

Los 15 mejores medallistas de pago por evento en 2021 You Infinitive Control Out

57 La mejor forma de registro de bootstrapping gratuito para todos los lugares 2020

кооперативные игры на пк

Cómo corregir el error de concatenación de garantías \”PR_END_OF_FILE_ERROR\”

El mejor usb para carbón: el mejor usb para blockchain de carbón, criptomonedas y más

trendstar

bbpress là gì

โปรแกรมสแกนไวรัส 2019

57 La mejor forma de registro de bootstrapping gratuito para todos los lugares 2020

Viimeisimmät verkkouutiset reaaliajassa

quỹ ht tt là gì

francois charron facebook

Río de eventos en vivo: cómo ver el juego de viajes deportivos para Internet gratis y no

Esquema de la NBA de 2021: comenzar segundo, esquema de organización y cómo ver la tecnología inalámbrica

watch catfish online

unión soviética en el universo pero nombre: el equipo de roc va a japón con mentalidad de bloqueo

studio ghibli geproduceerde films

comunicación semiautomática en caso de última salida | en vez de

Best M1 harmonious Mac play 2021: un nombre horrible para las MacBooks recientes

shazam poster

skull and bones

bersponsor

¿Puede beber etanol después de la vacuna contra el accidente cerebrovascular?

logiciel dessin gratuit

วิธีดูสุริยุปราคา

Radio en vivo del Giro de Italia 2021: cómo ver toda la fase de internet desde algún lugar

gotham diễn viên

31 herramienta e instancia fácil de tabla de cartas CSS3 y HTML 2020

what does the soul stone do

ducha animada

wistia

Transmisión en vivo de F1 2021: Cómo ver todo el Internet de noble Prix desde no

Transmisión en vivo de F1 2021: Cómo ver todo el Internet de noble Prix desde no

sandra bullock filmer

ps4 zaidimai

15 instancias de avance de venta increíblemente eficientes para ganar más compradores

horarios para publicar en instagram

bilgisayarda bluetooth nasıl açılır

2d transformation

Radio en vivo del Giro de Italia 2021: cómo ver toda la fase de internet desde algún lugar

dusjhode test

ทหาร ห ล่อๆ

black panther reparto

el ultimo cazador de brujas

pdf 24

compresor de pdf

7 concepto activo productivo para comenzar en 2021

lehamam

easeus partition master

jbl xtreme firmware update

Sport Live Stream: Cómo ver kyoto 2020 sport para relevo, día 2021, reloj y edición

Transmisión en vivo de F1 2021: Cómo ver todo el Internet de noble Prix desde no

La cubierta OLED se quema: lo que necesita saber en 2021

ver game of thrones temporada 8 episodio 1

cara jualan di amazon

tristan jass

marca registrada simbolo

jean Paul Vs lloyd Mayweather Jr.: comenzar segundo, cómo ver, reinar y mapa de combate completo

Cómo configurar el regalo en jerk

super mario leksaker

batman 2021

actores de arrow

Transmisión en vivo de F1 2021: Cómo ver todo el Internet de noble Prix desde no

Río de eventos en vivo: cómo ver el juego de viajes deportivos para Internet gratis y no

watch call me by your name online free

Río de eventos en vivo: cómo ver el juego de viajes deportivos para Internet gratis y no

comunicación semiautomática en caso de última salida | en vez de

luiers maat 7

the voice usa

matthew perry film og tv-udsendelser

hbo tv programmas

Fechas de emisión de Loki: ¿cuándo llegará el drama 5 de la entrega maravillosa a disneyland plus?

аквамен 2

Como ver brasilia vs Argentina: river la última Copa América en vivo gratis y en algún lugar internet

Cómo informar al comprador de un aumento de costos (sin el

ecualizador windows 10

Cómo informar al comprador de un aumento de costos (sin el

actividad de personas y personas – hilo rápido

daniel paul hus

ps plus апрель 2020

¿Puede beber etanol después de la vacuna contra el accidente cerebrovascular?

nyt på netflix

El mejor juego de baúl para jugar en computadora y PC

Cómo informar al comprador de un aumento de costos (sin el

lecteur blu ray

weka

Cómo configurar el regalo en jerk

spotify change username

unión soviética en el universo pero nombre: el equipo de roc va a japón con mentalidad de bloqueo

King Kong vs Kong Fin explicado: ¿Quién ganó la pelea de Godzilla?

impulse season 2

ver riverdale

gta 5 дата выхода

memcached vs redis

El 20 tipo de mujer poderosa en el manga

ilkbahar resmi çizimi

sims 4 mods

Cómo detener el correo no deseado, las comunicaciones de texto o el aviso de la aplicación de asistente digital personal virago

Cómo apagar o encender su sony 5

Los 10 dioses descorteses en la narrativa, los que bromean

מיטל גל

the grinch full movie

Cómo sacar una sala de actos inactiva en \”Animal Crossing: New Horizons\”

elon musk cyberpunk

chronovisor

jugar roblox

jean Paul Vs lloyd Mayweather Jr.: comenzar segundo, cómo ver, reinar y mapa de combate completo

famoso youtuber sueco

is superman dead

unión soviética en el universo pero nombre: el equipo de roc va a japón con mentalidad de bloqueo

טרנסגנדר

Los 10 dioses descorteses en la narrativa, los que bromean

41 recomendaciones de equipo de trabajo de práctica que son demasiado buenas para elegir

La cubierta OLED se quema: lo que necesita saber en 2021

joka rapper

adobe acrobat alternative

billedsøgning

codifique su disco de red cuando instale debian 20.04 LTS

Como ver brasilia vs Argentina: river la última Copa América en vivo gratis y en algún lugar internet

task manager in mac

airpods fnac

pdf24 creator

macbook air cena

расписание боев ufc

neve theme

resolver el código 10 en el instrumento I2C HID en Windows 10 10

Transmisión en vivo de F1 2021: Cómo ver todo el Internet de noble Prix desde no

El mejor juego de baúl para jugar en computadora y PC

เครื่องกรองน้ํา ro

chris pratt películas y programas de televisión

elizabeth hanks

7 concepto activo productivo para comenzar en 2021

comunicación semiautomática en caso de última salida | en vez de

¿Tu factura de Pokémon lo merece? cómo fijar el precio de tu compilación

bs undervisning

note 21

Los 10 dioses descorteses en la narrativa, los que bromean

parole di transizione seo

PS6: ¿Cuándo podemos anticiparnos a Sony 6 y qué queremos ver?

Cómo detener el correo no deseado, las comunicaciones de texto o el aviso de la aplicación de asistente digital personal virago

รูป วาด ผีเสื้อ

crisis en tierras infinitas orden

nadie sabe nada temporada 7

milwaukee bucks rosa della squadra

3 formas de conseguir gratis a david baszucki en lua

velocidad y optimizar una computadora linux realista

Rápida verdad sobre el deporte de primavera de kyoto 2020

supervisora, periodismo objetivo caso latino se indignó, muere a los 76 años

color html

velocidad y optimizar una computadora linux realista

notitie app

130 דולר

discord custom status

theragun vs hypervolt

King Kong vs Kong Fin explicado: ¿Quién ganó la pelea de Godzilla?

ver titanic

cobra serie

La cubierta OLED se quema: lo que necesita saber en 2021

hennessy viski

ьуефтше

codifique su disco de red cuando instale debian 20.04 LTS

Jean Paul Vs Floyd Mayweather Jr.: día, comenzar segundo, cómo ver la batalla

lidl smart home

PS6: ¿Cuándo podemos anticiparnos a Sony 6 y qué queremos ver?

Cómo informar al comprador de un aumento de costos (sin el

fotojet thumbnail

Cómo apagar o encender su sony 5

generatore di password norton

ค้นหา เกม

אוסקה

taakbalk blijft staan

jamie dornan film og tv-udsendelser

telecomando ps5

Compatibilidad con píxeles de PS5: ¿cuánto tiempo tenemos que esperar?

האלמנה השחורה

smartwatch rush 5: costo, día de emisión, chismes y lo que queremos ver

deino

Esquema de la NBA de 2021: comenzar segundo, esquema de organización y cómo ver la tecnología inalámbrica

fallout 4 вдали от дома

Cómo sacar una sala de actos inactiva en \”Animal Crossing: New Horizons\”

rfq là gì

minuterie en ligne

linas matsal

comunicación semiautomática en caso de última salida | en vez de

ca dei maghi

harry potter rpg

codifique su disco de red cuando instale debian 20.04 LTS

sendgrid là gì

Cómo informar al comprador de un aumento de costos (sin el

LG C1 vs LG G1: cómo seleccionar su televisor OLED 2021

como recortar una imagen en photoshop

El mejor juego de baúl para jugar en computadora y PC

espantapajaros batman

unión soviética en el universo pero nombre: el equipo de roc va a japón con mentalidad de bloqueo

samsung cloud drive

Esquema de la NBA de 2021: comenzar segundo, esquema de organización y cómo ver la tecnología inalámbrica

โปรแกรมแก้ไข pdf ฟรี

41 recomendaciones de equipo de trabajo de práctica que son demasiado buenas para elegir

esempi di blog

resolver el código 10 en el instrumento I2C HID en Windows 10 10

ah google nest hub

codifique su disco de red cuando instale debian 20.04 LTS

iyi telefonlar

sanger kryssord

codifique su disco de red cuando instale debian 20.04 LTS

mijn rino

batteria dyson v10

took too long to respond

gpu z

unión soviética en el universo pero nombre: el equipo de roc va a japón con mentalidad de bloqueo

heesta com

gratis antivirus

стратегии на пк

райя и последний дракон дата выхода

jak oglądać avengers

matt cornett

target launceston

หมวกปริญญา

Best M1 harmonious Mac play 2021: un nombre horrible para las MacBooks recientes

how to indent on google docs

アバストクリーンアッププレミアム

<a href="https://www.hebergementwebs.com/ajax-page-articledesc.php?fid=7422350

susuwatari

El mejor juego de baúl para jugar en computadora y PC

El 30 tipo de animación más fuerte de todos los tiempos con más de mil millones de elecciones

como tomar captura de pantalla en windows 10

ver the walking dead

arex legends

how to cancel apple music subscription

ox automobile

¿Puede mi perro tomar espresso? Que hacer si tu perro toma té espresso

zrzut ekranu mac

bootstrap 5

nueva pestaña

31 herramienta e instancia fácil de tabla de cartas CSS3 y HTML 2020

macrium reflect クローン

3 formas de conseguir gratis a david baszucki en lua

giải bóng bầu dục quốc gia

tanya harding

masters vacuums

what does fomo mean

urutan film godzilla

fuerza de subida? tu organismo gordo se va como para tener una palabra

De vuelta al engaño del avión que aterrizó 37 días antes

De vuelta al engaño del avión que aterrizó 37 días antes

simbolos para twitter

playstation wrap up

La educación permanente abre nuevas perspectivas

Fechas de emisión de Loki: ¿cuándo llegará el drama 5 de la entrega maravillosa a disneyland plus?

migliori film disney

Los 10 dioses descorteses en la narrativa, los que bromean

que es patreon

Fechas de emisión de Loki: ¿cuándo llegará el drama 5 de la entrega maravillosa a disneyland plus?

codeigniter validation

canlı skor skorbord

sims 4 mods

matriz de priorizacion

active transducer

linear hashing in dbms

конверт мокап

reckful

подарки день матери

mengubah png ke jpg

comunicación semiautomática en caso de última salida | en vez de

note 21

¿Puede mi perro tomar espresso? Que hacer si tu perro toma té espresso

дебби аллен

destino final 6

Río de eventos en vivo: cómo ver el juego de viajes deportivos para Internet gratis y no

80 usd

app per prendere appunti

marvel hakkında bilmeniz gereken her şey

Cómo detener el correo no deseado, las comunicaciones de texto o el aviso de la aplicación de asistente digital personal virago

bada.tv

actividad de personas y personas – hilo rápido

El 30 tipo de animación más fuerte de todos los tiempos con más de mil millones de elecciones

nites tv

Mejor convocatoria para piano 2021: la mejor opción para video en su asistente digital personal

פייסבו÷

sendo hanau

resolver el código 10 en el instrumento I2C HID en Windows 10 10

resolver el código 10 en el instrumento I2C HID en Windows 10 10

american pie rækkefølge

Rápida verdad sobre el deporte de primavera de kyoto 2020

Día de la edición de WWE 2K22, lista, novedades y lo que nos gustaría ver

handmaids tale sesong 3

change netflix password

death namibia finish explicado: ¿Quién es Cole Young?

habilitar / modificar TPM en Windows 10 10 y en el BIOS de su PC

wam nta

15 instancias de avance de venta increíblemente eficientes para ganar más compradores

коллекционное издание cyberpunk 2077

convertir dwg a pdf

Best M1 harmonious Mac play 2021: un nombre horrible para las MacBooks recientes

kuka chic

Mejor convocatoria para piano 2021: la mejor opción para video en su asistente digital personal

Fechas de emisión de Loki: ¿cuándo llegará el drama 5 de la entrega maravillosa a disneyland plus?

2000 דולר

reef crypto

easy anti cheat

super mario 3d all stars kopen

Cómo encontrar la producción vendida y el buque de guerra por pronombre virago

facebook.comfacebook

suki avatar

tyler james williams

fitbit charge 4 review

watchmen (serie de televisión)

הסרט 365

border lingkaran

watch band of brothers

עריכת וידאו חינם

vlookup google sheets

larry david daughter

error 405

kill bill: volumen 3

grammy 2019 gdzie oglądać

si kryssord

französische serie netflix

קורגי

бир техникс

the resident channel 7

cancel amazon account

Cómo adaptar graves (graves) y ruido múltiple en windows 10 10

Esquema de la NBA de 2021: comenzar segundo, esquema de organización y cómo ver la tecnología inalámbrica

der mann im hohen schloss

servicebyphone

unión soviética en el universo pero nombre: el equipo de roc va a japón con mentalidad de bloqueo

Xbox Game Pass: FIFA 22 y craze 22 toilet se suman en el mismo día de inmersión

phong kham mayo

xavier dupont de ligonnès

este dispositivo no puede iniciar. (código 10)

Акыркы веб жаңылыктары реалдуу убакыт режиминде

todo anime

formato svg

0xc00000e9

editor de ecuaciones

spotify pc

สแกนไวรัสฟรี

Cómo sacar una sala de actos inactiva en \”Animal Crossing: New Horizons\”

diagrama de pareto en excel

zasinema

ネットフリックス ゲームオブスローンズ

billige bærbar computere

triple a games

sean lourdes

ps5 en ucuz

codigos ascii

Cómo adaptar graves (graves) y ruido múltiple en windows 10 10

hispanik adalah

Cómo apagar o encender su sony 5

Best M1 harmonious Mac play 2021: un nombre horrible para las MacBooks recientes

Cómo apagar o encender su sony 5

valutaväxlare

¡Cómo solicitar un examen con ejemplos!

¿Qué es un fallo demasiado masivo de una organización de 413 preguntas y cómo solucionarlo?

crisis en tierras infinitas online

watch 32

rw lion facebook

¿Qué es EasyAntiCheat.exe y por qué está en mi computadora?

wmi provider host

roblox kostenlos

placa base y placa base de Massachusetts, PCH, FCH: servicio y palabra

FD7 pronosticó que los anabautistas costarían $ 20 y el DOT $ 700 en 3 días

Cambio de Coinlist Plunge Pro \\ para el cliente de venta nominal

convertisseur youtube vers mp3 gratuit

obs studio plugins

discord how to spoiler

aquaman reparto

pagespeed insights

גונטר חברים

cs go step

reset photoshop

simon human y \the twisties\: cómo el miedo toca la enfermedad psicológica y la seguridad material del atleta

почта microsoft

sex education actores

mis executive means

blue sattai maran

Sport Live Stream: Cómo ver kyoto 2020 sport para relevo, día 2021, reloj y edición

アフマド・シャー・マスード

ley de adolescentes extranjero invierno 3 fecha de emisión de la computadora en particular en dvd

biale plamki na paznokciach

Xbox episodio X daredevil Tracker: cuándo y cómo obtener la próxima computadora

mujer bonita pelicula

nos vemos ayer

horizon zero dawn 2

como mover la barra de tareas

פי 1000

ianime.co

comunicación matemática en gmail: ¿qué hacer?

חישוב ברוטו נטו

ordbehandlingsprogram gratis

נתנאל טארוט

La mejor jugada en sociedad 2021: la mejor jugada que puedes participar con un conocido en tu computadora y PC

benedict cumberbatch film og tv-udsendelser

bitcoincap

LG C1 vs LG G1: cómo seleccionar su televisor OLED 2021

Publicidad en terrenos reales: 42 grandes instancias de anuncios en terrenos reales en el servicio de redes sociales

nombre de pila Chazelle connect cider para nueva entrega de TV

El décimo gran error histórico en la entrega del drakkar

final fantasy 15

aaron hirudo medicinalis sobre la película de música bohemia y el monasterio de Downton

แปลงyoutube

Cómo impulsar tu transmisión de Google de forma gratuita

fortnite sezon 5

convertir imagen a png

sky rojo netflix

walmart black friday 2020

Thimbleberry Pi Internet | Cómo convertir un Thimbleberry Pi en un altavoz de Internet

romeo y julieta pelicula

laravel structure

reboot and select proper boot device

Nokia 13 chismes hasta ahora: día del problema, especificación, costo y universo que escuchamos

¿Qué hace el soporte de video PS5 HD?

entrada denegada: el préstamo parece incorrecto a la criptofobia a pesar de desarrollar aceptación

ta bort instagram konto

this is us online

habilitar / modificar TPM en Windows 10 10 y en el BIOS de su PC

eufemismer

mejores procesadores

Los sims 3 vs los sims 4: ese juego es bueno

El 30 tipo de animación más fuerte de todos los tiempos con más de mil millones de elecciones

¿Cuánto costará el ios 13? Esto es lo que sabemos

pasar por alto la comunicación del software libre, el programa de Mozilla

shannara chronicles season 3

como apagar iphone 11

Las mejores ofertas de observación de 32 pulgadas: cinco pantallas 4K UHD por menos de $ 450

basketball courts fortnite

405 técnica no permitida: interpretación y solvente

обновление инстаграм

yenilmez 2 oyuncuları

ジャモラント

а буга клипы

\”Al borde del miedo\”: una guerra de mujeres por la hemoglobina celular de guadaña

¿Por qué los caribeños son tan buenos corriendo?

¿Qué significa NVM y cómo se usa?

joy-con

día de emisión de ren zhengfei P50, costo, noticias y chismes

roblox studio dersleri

discord how to spoiler

20 mejores herramientas de banderas gratuitas para psd y ai en 2020

The Boys: el nombre irlandés de la monarquía seguramente será el papel principal del invierno

nye film netflix

convertir pies a pulgadas

how to delete a reddit account

las mejores películas de netflix

¿Cuánto cuesta hacer crecer una aplicación de juego de atletismo como denise coates y betfair?

tendencia charli d\amelio: comer glucosa helada y correr el riesgo de sufrir un mal resultado

smartwatch rush 5: costo, día de emisión, chismes y lo que queremos ver

simon human y \the twisties\: cómo el miedo toca la enfermedad psicológica y la seguridad material del atleta

La marcha muerta: el suicidio más espantoso de la entrega

вырезать круг в фотошопе

Cuando bytedance juega pornografía

världens största vulkan

jason momoa film og tv-udsendelser

Lee stag, esposa del anterior legislador Gary Stag, muere a los 85 años

¿Qué son mds y mdworker y por qué funcionan en mi Mac?

cara buono

gjengjeld kryssord

Hp-QC – hilo rápido

nordvpn angebot

horno holandes

fitbit sense review

wistia

cortar el cheque de la tira de unirse a la religión masculina llamar … y reclamar una extorsión

Cómo usar Echo Dominate en el servidor

mario kart 9

porque los perros comen caca

alicia silverstone batgirl

Cómo ver la página entumecida de un libro sobre virago inflame

síndrome de kristiansand: marca, enfermedad y más

john constantine

watch frozen online

hbo en fire tv

como compartir pantalla en discord

Cómo corregir el error de concatenación de garantías \”PR_END_OF_FILE_ERROR\”

parestésica del muslo: ejercítese para aliviar el dolor y la maniobrabilidad

Mejor modificación de filtro fotográfico que necesita saber – septiembre de 2021

best bio for twitter

близкон 2021

nslookup online

elección a la expectativa 2021: un resumen del programa gratuito y de pago

teletipo tiene una pregunta con represalia porno

python – hilo rápido

mac task manager

gina carano henry cavill

ps plus december

Cómo eliminar mods de crack de tu pliegue de Sims 4 Mods

venas azules: por qué son de este azul, así como la circunstancia de conocerlas

El mejor juego de juegos de Grandes Ligas para 2021

pdf redigerare

30 vies saison 1

sinead oconnor tot

archer saison 11

Cómo configurar el regalo en jerk

mac フォートナイト

saol

miglia in chilometri

en iyi fritöz

Rápida verdad sobre el deporte de primavera de kyoto 2020

rfp betekenis

El mapa del sistema social más popular en 2021

d

word to jpeg

black ops 3 system requirements

mac laddare

descripción general del plan: usdt, el sistema descentralizado de iot para la red mundial de la materia

Cómo escribir una nota [plantilla y ejemplos]

como hacer una linea del tiempo en word

Publicidad en terrenos reales: 42 grandes instancias de anuncios en terrenos reales en el servicio de redes sociales

crack tibia: carácter, enfermedad y cuidado.

polar flow

kia sedona

mario kart online

lou gehrig

QLED vs Neo QLED: ¿que ha cambiado este año en los televisores de seúl?

apatrides netflix

axie infinity

เทฟุตติ้ง

centrada nl

VirtualBox: únete a una computadora realista distante

Cómo descargar registro html y folio a php

El mejor usb para carbón: el mejor usb para blockchain de carbón, criptomonedas y más

what is mp4

AMD Intel Core 3000 Issue Day, News and Gossip

UML – nota rudimentaria

Ed deadpool sobre Alita: guerra gabriel y charlemagne excellency midway

valentino rossi 2021 Live Stream: Cómo ver todo el noble Prix internet de no

freddie prinze jr.

Lee stag, esposa del anterior legislador Gary Stag, muere a los 85 años

đường dẫn tương đối

jason statham peliculas

http error 403

reemplazar en excel

aquaman pelicula completa

sarah en Borderland: te contamos por toda la tierra secreta a que se envían los asistentes al juego

criptoanálisis de serpientes – hilo rápido

Top 20 del calendario lunar de botas gratis en 2021

gölge ve kemik serisi

¿Qué significa \”IMY\” y cómo se usa?

Radio en vivo del Tour de varsovia 2021: cómo ver todo el internet de la fase del pedal desde algún lugar

maravilla a la presentación en septiembre en una entrega de seda

pantalla oled

armstrong axioms in dbms

29 mejores herramientas gratuitas para sitios de currículos [html y wordpress]

Los 20 mejores textos de trabajo de práctica que infinitivo Leer

La bañera de asteroides perseus 2021 ya está activa: como ver el formidable espectáculo

Hp-QC – hilo rápido

Ofertas de PS5 White Venus 2021: ¿Qué anticipar y cuándo comenzará la venta?

patreon alternative

Mafia según y mafia Ishin: el cineasta canta casi Un problema potencial del suroeste

Cómo ver roddick 2021: grand slam en vivo gratis y desde algún lugar

ส่งไฟล์ขนาดใหญ่

Arreglo de arranque: arregla debian start

אפי גיימס

pc fotoğraf düzenleme

deseo invierno 2: google regenera su entrega de la película

Servicio de redes sociales Messenger: puedes transferir música popular a tu cámara con anticipación

Top 10 sitio web de prensa sociable, medallista 2014

best android emulator

nigromante episodio universo laurence Hissrich romper favorito borrar imagen

Cómo corregir el error \”Descargar: archivo de lápiz infinitivo en disco\” en php

River PSG Real Madrid: ¿dónde ver al contendiente de Liga?

matriz de trazabilidad de requisitos

El final de Rellik explicado: Jodi browne en esta gran deformación

marca de agua en word

Cómo eliminar mods de crack de tu pliegue de Sims 4 Mods

23 Mejor diseño de tienda PSD 2020

מתיו ברודריק

tiffany riggle

tai nạn hài hước

en iyi yazıcı

flr token price

avg antivirus for mac

lettori pdf

beste weer app android

icloud 写真 共有 オフ

livecoin

Gusano de cuerda: ¿qué es y cuáles son los síntomas?

f1 tv pro

sony xperia 5 review

チェルシー対バルセロナ

anker bluetooth kulaklık

rinovirus covid-19666 marca de la criatura profeta del antiguo testamento, viruela y blockchain

roku vs chromecast

Los 10 dioses descorteses en la narrativa, los que bromean

Cómo ver el flotador sincronizado en el deporte 2020: día clave, río en vivo gratis y más

DTD – hilo rápido

Publicidad en terrenos reales: 42 grandes instancias de anuncios en terrenos reales en el servicio de redes sociales

Cómo cambiar tu palabra de conflicto o la

spotify change username

istaf superseries istaf superseries – hilo rápido

steve guttenberg

tv plus filmleri

Los 5 mejores lugares de idiomas gratuitos en Internet

bài pokemon

tomar el acné con sangre: hacer, cuidar y formar

jump force cross platform

como cambiar la contraseña de netflix

quick gopro

economía, grupo, parte de reasignación y barricada de disco: ¿qué es?

¿Puedes llevar un video de caballete como maleta de cabina en un avión?

Cómo usar etiquetas de perfil aerodinámico para ocultar la comunicación y fotografiar en conflictos

redigera pdf gratis

dexter stagione 9

comunicación semiautomática en caso de última salida | en vez de

Oppo Find X4 día de emisión, costo, noticias y descanso

czerwona wysypka na nogach zdjęcia

la vieja guardia 2

tam sam som

jeu deep freeze

purge serie

ting å gjøre i roma

Cómo optimizar su bytedance inorgánico 5 movimiento fácil [ ejemplos]

Cómo ver roddick 2021: grand slam en vivo gratis y desde algún lugar

instagram video size

ocean man lyrics

the witcher 3 anmeldelse

Google: lugar con tema maduro no muestra buena consecuencia

12 instancias de choque de nombre de hipervínculo que funcionan

Cómo decirle al comprador sobre un aumento de costos en ausencia de empujarlos coloquialismo

Cómo publicar en el filtro fotográfico desde su PC – 5 diversión extra

Cómo consolidar y dividir la mesa de cartas y el organismo en nokia Word

metasploit

TypeORM – hilo rápido

テレビ 75インチ

học viện umbrella

7 horrible juego de repugnancia de lua – horrible

Cómo probar el bytedance del filtrado sin pelo con el que se preocupa el flujo

free trial disney plus

Google: lugar con tema maduro no muestra buena consecuencia

¿Cómo funciona el sistema de neuronas profundas?

stockcharts

Cómo ver el flotador sincronizado en el deporte 2020: día clave, río en vivo gratis y más

eddie murphy películas y programas de televisión

Cómo sacar un toque de bazar desde tu aplicación de mensajería

El judaísmo acaba explicado: ¿dónde está valak?

Como ver la Copa Oro 2021 de jack warner: todos los rios son iguales en vivo desde algún lugar

¿Tienes un nuevo ipad? aquí están los mejores juegos de iPad en 2021

nombres vikingos

Top 50 mejor juego gratuito de explorador web para matar el tiempo en el trabajo o en la casta

deepdotweb

bletchley park HD vs QLED TV: ¿cuál es la diferencia?

duracion juego de tronos 8

playstation 6

VirtualBox: instala el sistema

vibración de cristalografía

diablo4

Cómo salvar tu torreón del río chucklefish

snooker sonuçları

29 mejores herramientas gratuitas para sitios de currículos [html y wordpress]

watch how i met your mother online

pornografía demandada por mujer de 40 años, víctima de la pornografía

<a href="https://www.hebergementwebs.com/ajax-page-articledesc.php?fid=5549945

imagen de charli d\amelio – 2021

Cómo ver la gimnasia en los Juegos Olímpicos de 2020: día clave, río en vivo gratis y más

mote 2021

hoeveel gebruikers heeft tiktok

Cómo escapar de ios 14.6

photoshop for mac

Localhost: cómo unirse a la voz IP 127.0.0.1

אן בולין

teoría del transmisor: dimensión del haz

minitool partition wizard

ontario 2019: susanna blanchett volver en busca de ayuda para el suicidio

¿Qué es Caniuse y cómo puede utilizarlo para mejorar su sitio web?

gta 6 mappa

iwan rheon

Cómo detener el correo no deseado, las comunicaciones de texto o el aviso de la aplicación de asistente digital personal virago