The manufacturers and dealers and their marketing machine have got their message down to a fine art. Whatever size and shape their vehicle, they have a message targeted at their key audience to make it sound fun and frugal, sleek and seductive, mean and macho, whatever they deem we desire most in a vehicle. They have a service package and a finance deal to give you no excuses not to buy their incredible new car.

The government will tell you that new car sales are a good rule of thumb indicator for the performance of the economy as a whole. If people have confidence, they will make a major investment in a new car, companies taking on new people will lease more company cars, car hire companies will up their regular orders to fund the increased levels of business activity, and so on. Not only that, but we are told buying a new car is good for the environment because they are more efficient, their catalytic converters filter out more noxious chemicals and are therefore safer and more desirable.

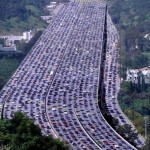

The problem is that, phallic symbols notwithstanding, there is still the secondhand car market and the fact that we scrap cars at a far slower rate than we used to. More car parts are now recyclable, but that does not resolve the issue of older cars that are not. Result? The sheer volume of cars goes up and up, and our nation is fast becoming a vast car park – the faster we try to move, the slower our journeys become.

For a relatively small island, our dependence on motor vehicles has grown to a frightening extent. in 2011 the RAC declared that there are 34m vehicles on our roads, of which 28.4m are cars, a rise of 34% since 1994. Our population is now over 60m, with an adult population of over 50m, and according to a 2009 FOI request there are over 34m licensed drivers in the UK. That means 83.5% of licensed drivers have a car, and there are two vehicles out on the roads for every three adults. Even allowing for the fact that some households accumulate cars like some people collect stamps, that is an awful lot of vehicles clogging up our roads and polluting our atmosphere.

The psychology of why we want our own space, our metal fortress, has been much discussed so I won’t dwell on it, shallow though it might appear, though the convenience argument of being able to travel door to door is highly persuasive, particularly when journeys by public transport are either impossible to schedule effectively (as discussed in my first transport blog), or fraught with other difficulties (signalling failures, train breakdowns, driver shortage, standing room only, and that’s before we think of the problems with air!)

If I’m commuting, as I have done for many years, a simple rule tends to apply: if I’m driving, I prefer trains, and when I’m waiting for trains I’d prefer to drive. But one rule always applies: when you’re on a train you can read a book or a paper, or in my case attempt to learn lines. Try doing that while driving! True, you can listen to the radio or music in either, though the novelty of that wears off after a while.

Arguably the worst commute I did was 9 months to and from Slough – a 176 mile round-trip on the A12 and M25 while there were no fewer than three major roadworks in progress. Oh, and I was directing a play in evenings and darn near falling asleep at the wheel. Not sensible, but then we do insist on driving through hell or high water to get to our destinations, cocooned as we are in our own metal prison.

Our comfort, convenience and satisfaction at the wheel is the primary means of selling cars, ahead even of performance and frugality. We want to feel king of the road and to treat our vehicle as if it were our home. Time was when you got precious few toys and gadgets to help, but now they are all the rage, sold with your new car at a healthy premium. CD stereos, electric windows, central locking, cruise control and climate control are now de rigueur even in superminis, and even average cars seem to have screens to adjust heating, stereo and satnav, so the middle and upper tiers of prestige manufacturers have moved onwards and upwards.

The one optional extra for which I paid a fair supplement on my car but truly appreciated is adaptive cruise control. This means I set the speed I want, and with the help of the infra red radar sensor the car accelerates or brakes, according to how far ahed the next car is. No right foot on the throttle, all I have to do is steer… and presumably at some point even that chore will be taken away as some kind of fly-by-wire device is fitted to our vehicles.

Ah, but now we have a climatically controlled environment, sumptuous heated leather seats, parking distance control, lights that create virtual daylight, music at the touch of a button, cars that drive themselves… what more could we want? Well, someone else to do it for us, I guess – and with public transport, that’s precisely what you get!

In the first transport blog, I pointed out the costs of motoring and how we are effectively a sponge to be soaked by the Treasury. The money earned from motorists is not reinvested in more and better roads, nor particularly in better public transport, but an economist would tell you that demand for the car is inelastic – we carry on using then, whatever the cost. At the marginal end of affordability, there may be a few people pushed off the road, but drivers make incredible sacrifices to keep their beloved wheels on terra firma.

And if we are discussing the costs, tax on cars and fuel are far from being the worst of it. Insurance costs a packet, and increases by the day. The industry points to the incidence of people cheating with false claims and other rackets, but I’d have thought this was the exception rather than the rule. Costs to insure cars, in spite of competition, seem to rise steeply year after year for most motorists, and young drivers are hit worst of all.

Add your son or daughter to your licence so they can learn, it costs. Add them as a named driver, you may pay hundreds or even thousands more. Let them pass their test and buy them a car, then the insurance goes through the roof – a year to be insured often quadruples the value of the car and stays exorbitantly high unless and until they pass 25 without any accidents. The actuaries tell you that statistically these groups are the highest risk, but punishing them financially won’t make it any easier if they can’t afford to get safe driving experience once they have passed the test.

Which reminds me: in my day, lessons cost £3.15 an hour and a driving test £7.50. Nowadays it’s often over £20 per lesson, and with the driving and theory tests coming in at nudging £100, it’s quite clear that nobody can afford to fail. I don’ve have the figures, but I do wonder if the double whammy of costs of driving will mean fewer people learn and therefore our roads will become less crowded. By 2080.

PS. This week my car went in for a service and MoT. It turned out to be a saga of additional jobs that needed doing, such that it will be in for a second night before I collect it tomorrow, £751 poorer. Not only that but it needs to return next week to get a split brake caliper replaced for another £400 or so, and I turned down the opportunity to get a range of other rather less urgent jobs done at the same time.

In truth, I can’t afford it at the moment, but have no choice: I can’t do without the car, and being without it brings home just how dependent we are on these gas guzzling monsters. Shopping today demanded walking to and from Tesco in Tiptree, which is not far but plenty far enough holding two large and heavy bags… but this was just a £20 light shop! Just imagine how difficult it would become if I had to rely on buses or needed a stack more shopping. Or, indeed, if I was elderly and infirm. Suddenly, with no car to take for granted, you feel utterly immobile. How sad is that?