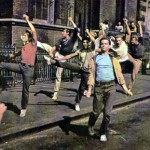

West Side Story is a very simple tale, a tragic love story between a boy and a girl from warring factions. It is Romeo and Juliet retold in 1961 NYC, the Montagues and the Capulets reformed as the Jets and the Sharks, respectively the fictitious but highly plausible Irish and Puerto Rican gangs of the 50s and 60s, a time when gang warfare and turfs were very much fought out in the poorer suburbs and gang deaths were a daily occurrence. Was this ever communicated more effectively than the finger-snapping opening to WSS? I doubt it. The sheer positive energy of the movie won over the many moaning critics.

The gang language may be dated nowadays, but many of the issues are bang up to the minute. But the sharp and slick satirical social commentary (told from both sides and from the perspective of the neutral observer) is one running facet through this beautifully nuanced tale, told in a stylised format but without losing one ounce of momentum or reality. But this is still the backdrop to the true romance, told with tenderness, and it is the passion and the ultimate tragedy that shines through songs like Tonight and Maria. For me, Somewhere is the essence of romance – a yearning prayer to escape the obstacles of everyday to be together. Sigh!

Thanks to Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim and Jerome Robbins it’s also arguably the most exquisitely composed, played, sung and choreographed musical in the history of the genre. A big statement to be sure, one with which many would disagree, but to my way of thinking the attention to detail in every aspect of this movie takes it to a higher level than even the finest of musicals.

Much of that detail will go over the heads of the audience, which is as it should be if you are totally engrossed in the movie, but the more you watch and listen the greater the experience will open up to you as you notice things you never saw before – a trait of all great movies, in my experience. One small example came when my daughter Lindsey was studying GCSE music, during which they examined one song from WSS – Something’s Coming. Listening to Lindsey’s explanation was something of a revelation, and no I can’t remember now, but there was so much greater depth to the song than I had ever envisaged. The pervasive rhythms taken from the latin tradition merge with the jerky melodies of gang warfare – a marriage made in heaven.

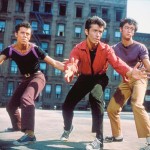

That detail is carried through to every aspect of the story. Jerome Robbins was originally the director as well as choreographer, but got sacked from the former in favour of Robert Wise, the producer, largely because his perfectionist detail was adding excessively to the time and budget. Dancers were forced to repeat moves countless times until Robbins was totally satisfied, no matter how blistered their feet became. You can tell how long they spent perfecting each and every step by the fact that in every dance move everything is done in razor sharp harmony. The most complex steps are completed with effortless economy, breathtakingly so – and for someone who is not a great fan of dance to say that says a lot about the movie. Just as the songs and plot carry home the social commentary, this is dance used eloquently as metaphor to convey the threat of the gangs. Even the death scene is performed in a stylised, choreographed format that conveys the underlying emotions better than just acting alone – the fights have a grace and dignity.

The cast was chosen with care from young actors, singers and dancers, building on the stage roles established on Broadway. It was a fine choice – George Chakiris and Rita Moreno both won Oscars for reprising their roles as the mainstays of the Puerto Rican community, but the ensemble cast works beautifully together.

As the star-crossed lovers, Natalie Wood (sung, inevitably, by Marni Nixon, the voice to many leading stars in musicals, not least Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady) and Richard Beymer bring to the roles of Maria and Tony the innocence of true love and the tragedy of love divided. Like Romeo and Juliet, they remain convinced until parted there is somewhere they can be together without fear of reprisals. As such, this is an anti-racist message years before the civil rights movement achieved its goals – almost revolutionary in 1961 and to many Americans in the Deep South unthinkable at that time.

Stylistically, WSS was years ahead of its time: the cinematography took the innovations of Citizen Kane and booted them up to the next level; most directors would have baulked at the use of bold primary colours, but here they speak volumes. The images heighten and underpin the social divisions and the hardened attitudes at play within the two gangs, let alone the language and social comment, which in turn were designed to forge a strong link with the younger audience, the people who potentially grew up against a backdrop of gang violence and intimidation and possibly to force them to confront their own intolerance and hatred.

But if you’re going to review musicals the ultimate test is the quality and longevity of the songs, and there is no musical better from that perspective. To include America, Tonight, Maria, I Feel Pretty, Somewhere, Cool, A Boy Like That/I Have A Love, The Jet Song, and even a satirical number like Gee, Officer Krupke (a savage and knowing analysis of how delinquent youth was – and is – passed from pillar to post by a society that could not cope with such nonconformity among teenagers, quite apart from their hellish rock & roll music!), in just one show is unprecedented and has no equal. Seldom if ever have musical numbers been staged with greater verve or inspiration.

Bernstein and Sondheim both had brilliant careers, but I’d defy anyone to say they ever achieved anything better, separately or together. However the success of the movie is about the collective genius of all concerned. That it was garlanded with honours is no less than you would expect, nor indeed that it was feted as one of the most “culturally significant” movies of all time by the US Library of Congress.