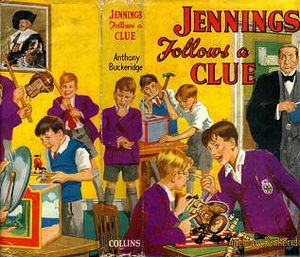

I read Anthony Buckridge’s Jennings and Darbishire books avidly from the ages of about 7 to 12 – until overtaken in my affections by Agatha Christie and other more advanced authors of whom my librarian mother did not necessarily approve. Even then they were very dated, but stupendously well-written and hysterically funny. I mean, I chortled, I guffawed, I laughed like a drain at very regular intervals – I laughed so hard my face turned lobster pink, no sound escaped from my lips and all I could do was sit still, my shoulders rocking gently.

Contrary to how they read now, my hilarity was caused not by the circumstances of boarding school education (to which I was not subjected), nor the arcane vernacular language, a mythical hangover from the class and independent education system prevalent in the era, but simply by the scrapes these two upper middle class schoolboys got themselves into at the fictional Linbury Court preparatory school – a minor public school for boys between 8 and 13 years of age of the type found at various corners of the UK and populated by the offspring of the aspirational well-to-do, though the aristocratic and seriously wealthy would sooner send their little darlings to very particular schools, la crème de la crème.

Although I did not see it at the time, it was every bit as class-conscious and class-ridden as Agatha Christie’s murders in manor houses, an idyllic view of a comfortable post-war society that included tradesmen, police, firemen, posties and suchlike, but excluded death, poverty, hardship, rationing or any serious unpleasantness.

Buckridge wrote 25 of these books between 1950 and the mid-70s – by which time they had become very foreign to all and sundry. They remain an historical artefact, much beloved presumably by ageing old boys from the 50s and 60s who also went to preparatory schools like Linbury Court, many of who might profess to remember their school days fondly and indeed to claim, as the cliché would have it, that they were the happiest days of one’s life, don’t you know? Even the Linbury Court alumni had a part to play, notably the gloriously named Lieutenant General Sir Melville Merridew.

The staff there had their foibles too – notably Mr L P (Lancelot Phineas) Wilkins: “Jennings’s form master, a man of little patience and a volcanic temperament very occasionally redeemed by a heart of gold” and Mr Michael Carter, “Jennings’s housemaster, a man of great imperturbability and patience, with a phenomenal ability to detect dissembling and violations of school rules.” The head, Mr Pemberton-Oakes, is a classicist and authoritarian, though not without decency or a sense of humour, whose exploits include the purchase of a super-8 camera from a salesman who believed he was visiting a private stately home.

Jennings and Darbishire, caught in a time warp somewhere back in the 50s, would in real life presumably have gone on to a senior public school, maybe to university and become pillars of society, tradition, acceptance and defence of the institutions of the British establishment, and careers in stockbroking and the church respectively. But Buckridge, writing primarily for children of all ages, chose to capture what he must have seen from his own upbringing as a golden age of boarding school life, the “happiest times of your life.” I imagine others view schooldays on a different plane.

However, the alternative reality in that era was often very different from the helpful and supportive institutions nurturing their charges at not inconsiderable cost to make them model citizens. Shame, for example, that remarkably little was written or said about the inhumanity of the British sending very young children away to boarding schools at an age when they needed loved ones all around them. Some, the more exuberant and outgoing, may have taken all this in their stride, but I suspect many more suffered severe homesickness and were simply told to grow up and be a man.

I include in this analysis all “public schools” (actually private, independent schools) within the British tradition and offering boarding for pupils at a price that only the seriously rich could afford, as mentioned before: Eton, Harrow, St Pauls, Charterhouse, Westminster, Rugby, Winchester and the other paragons of our noble virtues, to sort the wheat from the chaff.

There, the Jenningses and Darbishires of the day would have gained an education dominated by very traditional didactic teaching methods (much learning parrot-fashion), an expectation of total attention and discipline, adherence to the many school rules (though in retrospect many claim they broke these at regular intervals and suffered the consequences), and lessons dominated by classics (Latin, ancient Greek, ancient history etc.) and religious devotions, regardless of their practical value in any given career – those were secondary considerations compared to the art of “being one of us”. This reminds me of a rhyme quoted by Jennings:

Latin is a language

As dead as dead can be

It killed the ancient Romans

And now it’s killing me

They would play rugby in winter and cricket in summer, and also eccentric pastimes like the Eton Wall Game. Even war games too!

And as with all institutions supporting establishment and traditions, there were and probably still are many obscure and sometimes bizarre rituals and artefacts handed down over centuries to lend an air of mystique and permanence. In short, these were and are institutions that believed themselves to be custodians of quintessential and noble British virtues (if any such thing ever truly existed), charged with the responsibility of passing on these to following generations.

Such schools were and are thought by many to be the training ground for many politicians from well-to-do backgrounds (12 of our current Cabinet went to private schools, including Prime Minister Cameron who was educated at Eton), the senior civil service, the armed forces, church, banking and the senior ranks of other institutions. Regardless of intelligence or aptitude (and let’s face it, we’ve suffered royally at the hands of bad leaders in many spheres), they were given a grounding in leadership, perhaps to reinforce the class divide widely caricatured of British society for hundreds of years – though the number of senior appointments from such schools to this day suggest this is far from coincidence.

Part of the ethos of such schools was unquestionably to “toughen up” youngsters with a regime which, in what their alumni would regard as the golden era, would include cold baths, inedible food, prehistoric living conditions in dorms, routine bullying, use of the cane and even more cruel and sadistic forms of corporal punishment meted out by masters on errant students, some of which behaviours are exemplified in Lindsay Anderson’s memorable film If – which I heartily recommend for its savagely satirical depiction of public school life, even if the ending is more fantasy than reality.

This was supposed to teach virtues like unquestioning acceptance of authority the traditional English “stiff upper lip” – fortitude in the face of adversity and avoidance of outward expressions of emotion. Small wonder we brought up generations of stoic and emotionally crippled men who bottled up feelings and punished through beatings those they deemed inferior or their children (and even wives.) A substantial proportion would have gained a sense of natural authority, of effortless superiority the rest of us, taught in state schools (a boys Grammar in my case, allocated following the notorious 11 Plus exam), thus reinforcing the difference between “them” and “us.” These are people bred and trained to win rather than to find the niche that brings them and us moderate happiness, fulfilment and productivity. Therein lies the difference.

Vive la différence, they would say – one size does not fit all – though of course our PM now has to downplay his posh upbringing to make it sound at least as if understands the lot of the common man (using the NHS despite being a millionaire many times over, for example.) A common perception is still that the wealthy benefit from his policies far more than those without money or privilege.

However, that image of public schools hid a dark side (at least in the bad old days – I wouldn’t like to comment on what happens within those hallowed walls these days.) It’s accepted fact that sexual abuse in such institutions was at one time rife, though in view of the greater sensitivity to such matters these days one hopes such behaviours are no longer tolerated. The system of “fagging” was once such, whereupon younger boys were required to act as personal servants to senior boys, notably prefects. In the course of their duties (to which masters turned a blind eye), boys were frequently the subject of abuse by their elders, and in some cases masters too.

To have spoken about it to anyone would have resulted in very severe beatings and, worse, not to have been believed, so the abuse and rape were kept hidden, and worse – buggery of innocent young children was almost regarded as a rite of passage in some of these institutions. No doubt the vast majority of victims and abusers went on to marry and have many children, but the trauma caused by the abominations of the fagging system remained silent – much as the abuse conducted by Catholic priests and entertainers was successfully hidden for many years.

Strangely enough, the sexual abuse did not stop there. I’ve heard several accounts recently of pupils at such schools being sexually molested by matrons, sometimes from ages as young as 10 but certainly in the teens. While some masters may well have chosen their profession as a means of finding beautiful young boys ripe for the plucking, some matrons may well have had the same predilection. A friend of a friend was apparently traumatised by his treatment by senior pupils but also seduced by a youngish matron at a tender age, from whom he developed a taste for large breasts (though there is no requirement to have been thus seduced to enjoy large breasts!)

I have no doubt there are plenty of inmates who suffered no such abuse and had a rip-roaring time at their alma maters, but plenty of others suffered sexual abuse in private and in silence. They suffered for their family honour, you might say, and in so doing suffered years of trauma. Who knows what effect it had on their adult lives and ability to express their own sexuality? Maybe the torture was passed on to future generations, as abuse often is?

In view of the Jimmy Savile scandal and its aftermath, it amazes me that nobody has even talked about investigating the past sexual abuse and regimes of violent punishment that took place in such schools. Or rather, it doesn’t surprise me at all, given that they are effectively institutions within the establishment.

Actually, there have been rare instances of abusive headmasters or senior masters being prosecuted following complaints from students much later in life, such as Nigel Leat at Hillside School, Anthony Brown at Godolphin School, Bruce Roth at Wellington College, and several others. I’m not saying this behaviour was exclusive to public schools (a Panorama investigation revealed as much) but clearly boarding schools, where pupils are on their own, vulnerable and without the support of family, the temptation for those drawn to such behaviours was all the greater.

Where, you might ask, was the pastoral care provided by these institutions who were, after all, acting in loco parentis? But you were expected to continue defiantly, and “Play up! Play up! And play the game,” as Henry Newbold so memorably put it.

So what would Jennings and Darbishire have made of Linbury Court in 2012? No doubt girls would be admitted, caning would be abolished and staff would be far better trained to deal with their teenage needs and to suppress their own private predilections. Parents would be encouraged to visit more frequently and fagging would have been consigned to history. The curriculum would have been markedly updated, perhaps even to include computers and encouraging pupils to gain alternative views of reality. Would the education have been diminished as a result of these changes? I think not, but almost certainly those destroyed by the system would have been given a far more sympathetic hearing.

For people of my generation, trained to be internationalists, strategists and big-picture thinkers, we see much small-mindedness about these institutions, though in fairness much will have changed since the 60s. We could do without the preservation of rank and privilege though and instead enable every young person to be a free-thinker.

PS. For the record, I “passed” the 11-plus, was educated at Wilmslow Grammar School for boys, an elitist state school, but do not look back upon said education fondly. It was what it was, but do I feel selective education offered more opportunity or superior education than my kids obtained at The Broxbourne School? Not in the least! Quite the reverse, in fact.