Doubt shall not make an end of you

nor closing eyes lose your shape

when the retina’s light fades – Brian Patten

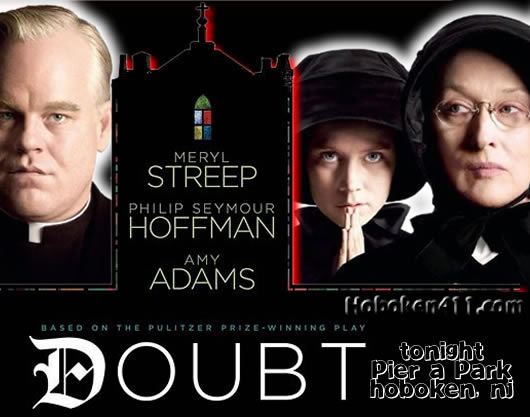

Doubt is a provocative battle of the heavyweights, 15 rounds, no holds barred. In the red corner, Philip Seymour Hoffman as Father Flynn, priest at St Nicholas’s Church in the Bronx and suspected serial paedophile, having possibly (or possibly not) seduced a young black altar boy with the help of altar wine; in the blue corner, Meryl Streep as Sister Aloysius, feared, repressed and reactionary Principal of a Catholic school in 1964 USA. The referee for this contest is sweet, innocent novice Sister James (aka Amy Adams, she of the doe eyes and slack jaw.) Ding ding.

Based on a Pullitzer-winning play and retaining a stagey feel in spite of being opened out, Doubt is John Patrick Shanley’s homage to Catholic guilt par excellence: Ignore the evidence, trust the beliefs, suppress the doubts.

You’d have to say this tale is told very much with the benefit of hindsight – the very idea of La Streep’s character suffering a crisis of conscience and siding against the priest and the Catholic hierarchy is very far fetched. Indeed, that such a character would show any signs of weakness, let alone several shrieky rants and much mouth-foaming self-righteous indignation, stretches credibility somewhat. Sister Aloysius has of course not a shred of evidence for her assertions, though the tipping point is her lie, a mortal sin. Her crocodile tears didn’t convince me she felt any doubt.

But in this case we never know for certain precisely what the very persuasive Flynn has or has not done, only that he has some element of guilt lurking in his conscience. He begins the film with a powerful sermon about doubt, conducts another on the theme of intolerance, then preaches about gossip, and finally bids a fond farewell to his parishioners. Flynn loses the battle but apparently wins the war, before heading off for a promotion. And with that we must remember how in reality paedophile priests were never exposed, were protected by their superiors, and went on to abuse many young boys (and girls) along the way, the world over. As soon as Flynn departs the parish, the good sister lets it go.

To my mind, Hoffman wins the battle of the actors by two falls to a submission, and it is Streep’s unconvincing final speech confessing doubt to Adams that nails it for me. However, the support from the boys, especially James Foster II as the unfortunate Donald Miller, and particularly the excellent Viola Davis (who was brilliant in The Help) bring home the emotional intensity of this drama. It is also set and shot beautifully, with much use made of swirling autumnal leaves and claustrophobic classrooms.

Doubt will not persuade anyone that Catholicism has anything but a black stain on its soul, but it will make you wonder whether confession is good and whether everyone has secrets they dare not reveal.