There is a scene at the beginning of Broken Flowers, a movie largely dealing with the theme of non-communication between people who should be equipped with more emotional intelligence, in which Bill Murray‘s character Don Johnston (no relation) is sitting on the sofa of his large and well-appointed home watching the movie of Don Juan – and in his day this Don J was very much a ladies man. His face is flat, impassive, almost impenetrable. His girlfriend Sherry (Julie Delpy) walks downstairs in a pink suit carrying a case and a holdall, and announces she is leaving. They exchange a few words but might just as well have been speaking respectively in Urdu and Swahili for the total lack of mutual understanding.

She turns and goes through the door. He runs to the door and yells, “Sherry.” She stops. He says nothing. She continues to her car and drives off. Johnston goes back to his sofa with the movie playing. His eyes are turning in their sockets but the face betrays nothing, not one flicker of emotion.

He lies on the sofa and falls asleep. Does he love Sherry? Is he distraught at her departure? Why did he not stop her? What is it he wants from his life, having retired a rich man from the computer business? We don’t know, we can’t tell – except that for whatever reason he cannot deliver the passion and intimacy Sherry desires. A Freudian therapist would have a field day uncovering the back story behind Johnston’s repressed psyche.

This moment displays instantly the beauty of Bill Murray as an actor, precisely the same skills he used to great effect in Lost in Translation and other movies in the latter half of his fine career, once he made the transition from being primarily a comedian to a serious actor. He does deadpan as well as, better even than the late great Leslie Nielsen, but in so doing he hints at hidden depths, which in Broken Flowers are revealed slowed, a fine and subtle striptease of a performance in which he takes a journey, literal and metaphorical, and finishes a different person from the man who began the voyage of exploration into his past, and thereby self-discovery – of a sort. Whether Johnston truly learns lessons you somehow doubt.

Don Johnston is a man who observes much but takes time to reach conclusions. His conversation is punctuated by long meaningful silences filled with the slow crunch of cogs whirring. He suffers a serious case of paralysis by analysis!

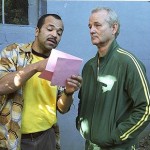

His source of confusion? Don is thrown by the arrival of an anonymous letter which tells him that he is a father of a son by a girlfriend he knew 20 years before, which son is on a journey to find his father. His initial reaction is to shrink back but he is challenged to act by his friendly and organised amateur sleuth of a neighbour Winston (Jeffrey Wright) to go visit all the girlfriends he can remember and to find which wrote the letter. It is this quest that enables him to face up to his past and identify who or what he really cares for – and ultimately recognises the true intensity of loneliness he feels. He has, as the French put it, un coeur en hiver – a wintry heart, which by the end of the movie is fast melting.

Of the five women on his list, one died in a car accident, something Johnston comes to regret bitterly since he can no longer meet her. The other four – played beautifully in turn by Sharon Stone, Frances Conroy, Jessica Lange and Tilda Swinton – are all radically different and also much-changed with the passage of time. And each encounter is, in different ways, supremely uncomfortable for Don; the discomfort is etched on Murray’s scarred face.

Whatever he saw in each at the time is long gone. They did not conform to a type other than being earthy and sexual. Each in their own way challenges him: in the case of Stone’s Laura it is by the naked appearance of her daughter, provocatively named Lolita, though he still ends up in Laura’s bed; Don endures a tense and embarrassing meal with Conroy’s Dora and husband, largely in silence; Lange’s Carmen is an animal communicator and clearly not on the same planet; and Swinton’s Penny has a grudge against him, such that he is beaten up by her biker friends. But none volunteer to being the mother of his hypothetical son. The boy he does meet may or may not be the one, but he is spooked by Johnston’s behaviour, fearing a gay molester. The ambiguity is there but so are the emotionally raw loose ends – which seems to me rather more like real life than usually painted by Hollywood.

The substance of the movie is worthy of viewing, though it could have been made stylistically in a number of different ways. Jim Jarmusch chose to make it as a slow-moving, poignant, gentle, erudite comedy of dysfunctional relationships, the sort where the camera lingers on actors’ faces for an uncomfortably long time in a prurient attempt to psychoanalyse their deepest feelings.

While to me this is much more of an bright yet subtle drama, I will honour the categorisation claimed and hope you find a smile. After all, this is not a place to look for belly laughs, but it is big on wry humour, verbal and observational. The use of metaphors, not least the broken flowers of the title, is well-judged. They respect the intelligence of the audience, they allow us to draw our own conclusions.

With an actor like Murray you can get away with that approach, not least his minimal screen acting; audiences looking for his Saturday Night Live and National Lampoon persona would come away sadly disappointed. This is a mature, grown-up Murray and a mature grown-up movie, one that tells you much about the anxieties of ageing without verbal histrionics and agonising only in a very minimalistic way.