Benjamin Button is a movie of paradoxes. Based on a 1921 short story by F Scott Fitzgerald, it translates to the big screen at a not insignificant 158 minutes in the hands of esteemed director David Fincher. It tells the story of a man born ancient and decrepit, who steadily grows younger until at death he is a babe in arms, while his star-crossed soulmate starts young and ravishing but ages in a genteel fashion until she is at death’s door and listening to the history of Benjamin retold from his memoirs by her (and his) daughter Caroline while Hurricane Katrina whips up a storm outside the hospital windows in New Orleans, Louisiana.

It is told in a deceptively simple folksy style of narration similar to that which won many plaudits for Forrest Gump, but in the final analysis is the better philosophical parable by virtue of its message about aging and what really matters in life without the help of clichés of the “life is like a box of chocolates” ilk. In fact, it is told with some delicacy and limited action, which meant that some among its viewers lost patience and grew bored in the telling. These included a fair number of reviewers, including those who described it as “one of the worst movies ever” and “twee and pointless” – so there is no doubt that this movie does polarise opinion quite successfully. Well, advance warning that I am going to disagree with those reviewers!

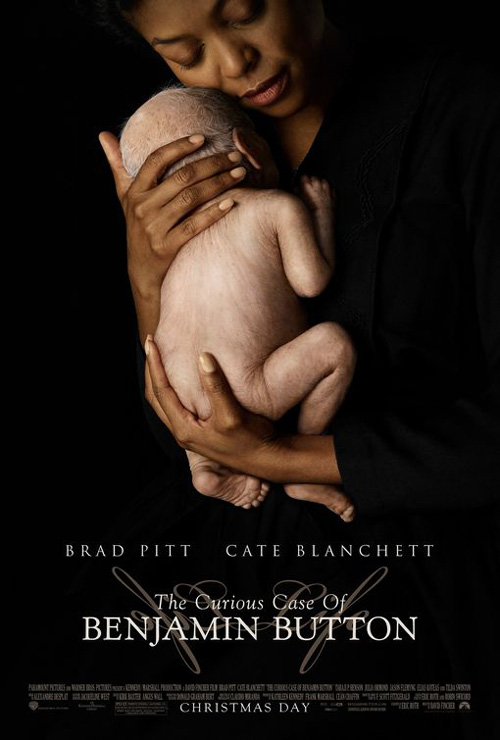

In fairness, the plot is not huge, but, by design, elliptical if not parabolic. That is, Button is born, finds his way into the arms of earth mother Queenie, grows up, goes to sea, learns about life and returns at regular intervals to meet the effervescent red-headed beauty that is Daisy, told retrospectively – as most films seem to, these days.

Their relationship is the fulcrum of the movie, the pivot on which the story balances, especially the glorious purple patch when the two collide in middle age, in which after years of a loyal but separated friendship they finally get together, achieve the radiant happiness you always knew they had in them, the by product of which is their daughter. But since they are heading in opposite directions that happiness could not last, and Benjamin rambles off, as the grizzled blues legends put it. He departs with his motorbike and the clothes on his back, travelling while turning gradually into a teenager – and Pitt’s make-up progressively younger with it.

Brad Pitt, an actor more studied than some of his contemporaries, gives a quiet dignity to the adult Button, and looks the part from his aged prosthetics down to young and beautiful as an old man. Cate Blanchett is unquestionably gorgeous, but also more resilient than many of her contemporaries. She gives a feisty display as Daisy the dancer, but becomes with age a figure of graceful proportions, and ultimately a mother to Benjamin in his final toddling years of dementia. A fine performance, as you would expect, though arguably the best acting is in the hands of Taraji P. Henson as Queenie, for which she justly got a Best Supporting Actor nomination.

The moral of this tale appears to be make the most of what you have and enjoy life and those you love whatever age you are: don’t let your chance go by, and certainly don’t regret your youthful indiscretions. But the movie of Fitzgerald’s story amply demonstrates the reality that to live life one must experience loss to become old. And if the cliché applies and only the good do die young, Button manages that – at an advanced age.

Fitzgerald, who himself died an alcoholic at 44 leaving a relatively good-looking corpse, wrote many stories about youth and vitality, would have made an excellent literary predecessor of the My Generation era (“hope I die before I get old” – though Messrs Townshend and Daltrey seem to be doing nicely at an advanced age.) Alas, many great writers died way too young. What would Fitzgerald have written about, had he become old? But I digress.

Strangely enough, I found Benjamin Button held my attention throughout, no mean achievement in a world hooked on instant gratification. It looks ravishing at every juncture and, to give credit to Fincher, has been framed beautifully to fit its proportions, more than you could say for other lengthy pictures – even if some found it way too long.

Best of all, there is no “explanation” of Button’s life in reverse, other than a clock at the station created by Mr Gateau deliberately to run backwards, and which is replaced then overrun by flood waters the moment of Benjamin’s death. Button’s fascinating life is what it is, a perfect metaphor. Button the movie is good on the eye, a tale well told and well performed. You can’t ask for much more than that.