The rite of passage cliché is that a father takes his son to the pub at the age of 18 or maybe slightly younger, buys him a pint of bitter or lager, sits him down and says: “Now lad, you may not like this at first but sip it and get used to the flavour. This is a man’s drink so take your time and enjoy.” Of course, the son would play along but wouldn’t have the heart to tell dad he was already drinking beer on a regular basis with his mates, quite possibly at the same pub, and was hoping the landlord wouldn’t greet him by his first name.

If the pub is the traditional setting for a relaxed British gathering, the pint is the appropriate medium of social exchange, that which promotes relaxation and loquaciousness. Granted that spirits or strong ciders may get people drunker quicker, but the point about the pint is that you can sip it or quaff it. Like wine it can be subtle and complex or merely an alcoholic fizzy drink to fuel social occasions, but the key definition is that of Real Ale, according to the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA, of which more later):

What is real ale?

In the early 1970s CAMRA coined the term ‘real ale’ to make it easy for people to differentiate between the bland processed beers being pushed by the big brewers and the traditional beers whose very existence was under threat.

Many pubs and brewers use the term to describe their beers, but, just to keep you confused, they are also called cask beers, cask-conditioned ales or even real beer! In the pub the huge majority of real ales are served using traditional hand-pulls, rather than through modern fonts, but there are some exceptions to this, so if in any doubt, just ask. Real ales may also be served direct from the cask, often called gravity dispense.

What makes real ale ‘real’?

Real ale is a natural product brewed using traditional ingredients and left to mature in the cask (container) from which it is served in the pub through a process called secondary fermentation. It is this process which makes real ale unique amongst beers and develops the wonderful tastes and aromas which processed beers can never provide.

What’s the difference between ‘ale’ and other beers?

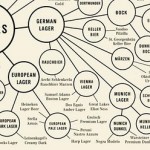

There are a huge range of different beer styles, each with different qualities, tastes and strengths, but each falls into one of two main categories; ale or lager. The key difference between ales and lagers is the type of fermentation.

Fermentation is the process which turns the fermentable sugars in the malt into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Lagers are made using bottom-fermenting yeast which sinks to the bottom of the fermenting vessel and fermentation takes place at a relatively low temperature. Authentic lagers then undergo a long period of cooled conditioning in special tanks.

Ales, which includes bitters, milds, stouts, porters, barley wines, golden ales and old ales, use top-fermenting yeast. The yeast forms a thick head on the top of the fermenting vessel and the process is shorter, more vigorous and carried out at higher temperatures than lager. This is the traditional method of brewing British beer.

Why isn’t all beer real?

Real ale is a natural, living product. By its nature this means it has a limited shelf life and needs to be looked after with care in the pub cellar and kept at a certain temperature to enable it to mature and bring out its full flavours for the drinker to enjoy.

Brewery-conditioned, or keg, beer has a longer shelf life as it is not a living product. Basically, after the beer has finished fermentation in the brewery and has been conditioned, it is chilled and filtered to remove all the yeast and then it is pasteurised to make it sterile. This is then put in a sealed container, called a keg, ready to be sent to the pub.

The problem is that removing the yeast and ‘killing off’ the product through pasteurisation also removes a great deal of the taste and aroma associated with real ale. Because there is no secondary fermentation occurring in the container (i.e keg) in which is held, there is no natural carbonation of the beer so gas either carbon dioxide or a mixture of carbon dioxide and nitrogen has to be added to “fizz up” the beer. This creates an unnaturally fizzy beer rather than the gentle carbonation produced by the slow secondary fermentation in a cask of real ale.

What is beer?

All beer is brewed from malted barley, hops, yeast and water, although other ingredients such as fruit, wheat and spices are sometimes used. The yeast turns sugars in the malt into alcohol and the hops provide the bitter flavours in beer and the flowery aroma.

The flavour of the beer depends on many things, including the types of malt and hops used, other ingredients and the yeast variety. Getting the yeast right is essential as each variety has its own distinctive effect on the beer.

Of the many beers available, each will have different characteristics, though typically they fit into one of a number of styles, each of which has a range of sub-divisions with various flavourings and manufacturing techniques (see pictures below.) From darkest to lightest:

- Stouts like Guinness – black or very deep amber in colour, often with a sweet chocolatey taste

- Ales – bitters, pale ales and many other varieties fermented at warm temperatures, tending to bitterness with body

- Lagers – generally pale and light in body and flavour, through cold fermentation, and by far the most popular style around the world

- Wheat beers, mostly continental, and including wheat as well as malted barley in the fermentation process.

Since they vary from “non-alcoholic” through to alcohol by volume similar to wine, it’s hardly surprising that beers can be different things to different people, but typically a “session ale” might be 3-4% proof, strong ales 4.5-6%, and special ales sipped in small quantities higher than that.

Personally I’m a devotee of “real ales” more than anything, especially bitter and true IPA (India Pale Ale) though I do like well-kept examples of every style. The malted barley creates a delightful base, enhanced and embittered (as it were) by the presence of hops. A recent trip to the Brewing Museum at Burton-on-Trent showed much about the development of the art form of brewing good beer.

The first thing to say about proper British ales is that, unlike the American myth they are not served “warm” but, if treated properly, are “cellar cool” – the temperature of the cellar in which they have been kept to perfection so when the the beer is poured (from a proper hand-pump of course), the depth of flavours are preserved and enabled to flourish. To my taste this is infinitely preferable to over-chilled American lagers, which taste of precisely nothing and even if they did are served so cold that you could not distinguish any flavour anyway – but then to a certain class of drinker, that is fine. The point is surely to enjoy the drink, not line your throat with ice?

To be fair, if you steer clear of the big breweries in the US, there are lots of wonderful microbreweries to be found, particularly the purveyors of steam beer, a style trademarked by Anchor Brewing in San Francisco, but also used generically to describe the method used by many such breweries, the antithesis of the lager style. Seattle is a great city to find bars and restaurants with microbreweries attached, and I’m delighted there are still a few of them to be found in the UK too, one such being the wonderful Slaughterhouse Brewery, attached to the Wild Boar pub in Warwick.

The British industry, while still in the thrall of “tied houses” where the beer brands on sale are predetermined by the brewery chains who employ a landlord to run their pubs, does include a fair number of “free houses” whereby the pub can obtain casks of many guest beers from the various small brewers dotted about the country, and often given eccentric names to stand out from the crowd. There’s something highly endearing about names like Old Peculier, Brewer’s Droop, Sheepshaggers, Toad’s Croak, Fursty Ferret, Admiral Byng, Grumpy Bastard, Dragonslayer, Jail Ale, Leg Warmer, Pigs Ear and Old Slapper on Poole Quay, to name but a few (see here for lots more) – most of which brands are owned by smaller independent breweries.

However, the biggest brands are brewed by giants of the industry like (see here for the top 50 list), notably Carlsberg & Heineken (which took over Scottish & Newcastle in 2008), AB-Inbev UK (the amalgamation of Belgian giant Interbrew with American monster Anheuser-Busch), Molson-Coors UK (who among many other brands now own the aforementioned Burton Brewing Company), Diageo PLC (owners of Guinness) and a few more. These companies, several originating in other countries, have hoovered up many of the best known smaller breweries in order to own the best-selling brands. Traditional big brand brewers from the past, such as Whitbread and Mitchell & Butler have now left beer behind in order to focus on hospitality of one sort or another. There is a consequently a big gap between our remaining native brewers and the multinational giants who flog the sort of brands you see advertised on TV, though it is encouraging to see the likes of Banks’s and Adnams thriving in the current market.

You pays your money and takes your choice, though mine is unquestionably to support the small brewers and to drink the fascinating and varied ales originating in pockets of the UK, though like many of our wonderful country pubs I fear that more and more will be scooped up by the giants and cease to be. It’s a great shame, though luckily we have CAMRA fighting their cause and a good number of Beer Festivals (including CAMRA’s own festival at London’s Olympia in August) around the provinces to preserve these delightful brews, traditional and modern alike, and win new audiences for them.

CAMRA’s main purpose is simple:

CAMRA, the Campaign for Real Ale is an independent, voluntary organisation campaigning for real ale, community pubs and consumer rights.

CAMRA was formed in March 1971 by four men from the north-west who were disillusioned by the domination of the UK beer market by a handful of companies pushing products of low flavour and overall quality onto the consumer.

Many brewers during the late 1960s and early 1970s had made the decision to move away from producing traditional, flavoursome beers which continued to ferment in the cask from which they were served, and such a move was opposed by Michael Hardman, Graham Lees, Jim Makin and Bill Mellor, all of whom thought it was about time British beer drinkers were given better variety and choice at the bar.

With this in mind, it was inside the westernmost pub in Europe – along the Kerry coast – where the first foundations of the Campaign were laid. With the quartet appointing themselves as secretary (Lees), treasurer (Makin), events organiser (Mellor) and chairman (Hardman), the Campaign for the Revitalisation of Ale was born on Tuesday March 16th 1971.

While the newly formed Campaign’s name was altered at AGM in 1973 to the now universally recognised ‘Campaign for Real Ale’, CAMRA’s core aims to promote real ale and pubs, as well as acting as the consumer’s champion in relation to the UK and European beer and drinks industry, remain to this day.

Following the formation of the Campaign and the first AGM – at the Rose Inn, Nuneaton in 1972 – where early membership records consisted of the four founders and their friends, interest in CAMRA and its objectives spread rapidly, with 5,000 members signed up by the following year.

In the present day, CAMRA has 149,424 members across the world, and has been described as the most successful consumer campaign in Europe.

CAMRA supports well-run pubs as the centres of community life – whether in rural or urban areas – and believe their continued existence play a critical social role in UK culture. CAMRA also supports the pub as the one place in which to consume real ale (also known as cask-conditioned beer, or cask ale) and to try one of over 5,500 different styles now produced across the UK.

And that is the point – cask-conditioned ales are at the heart of the community and should remain so. Long live the British pint!

PS. If you wanted to know what my favourite bottled beer is right now, the answer is Innis & Gunn original, described thus: “smooth Scottish beer with hints of toffee, vanilla and oak.” A fine craft brewery, I’d say :).

TASTING NOTES

- Smell: Caramel and rich roasted malts

- Taste: Incredibly smooth with a delicious toffee character and a light hop fruitiness

- Finish: Creamy and warming

- What to have with it: Curries, grilled seafood, good-quality burgers, juicy steaks