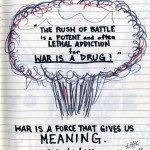

Katheryn Bigelow‘s big Oscar winner opens with a quote from War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning, a best-selling 2002 book by Chris Hedges, a New York Times war correspondent and journalist:

“The rush of battle is a potent and often lethal addiction, for war is a drug.”

This is a movie about the drug of war, the motivation that keeps a mob disposal team engaged in Iraq on the road in spite of facing instant death every minute of every day, about the camaraderie that keeps the team together, and in the final scenes, about how out of place they are back in their native American domesticity with the family and faced with choices like picking one pack of cereal out of the thousands on offer. There is no solution but the adrenalin of war.

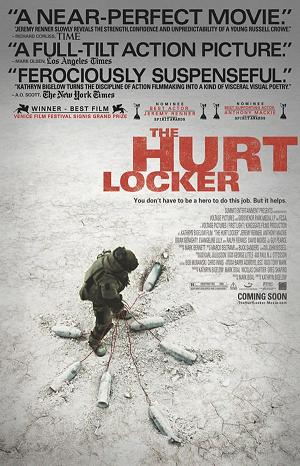

For the rest of us, The Hurt Locker is certainly in part as Empire magazine is quoted as saying on the cover of the DVD case:

“The most stunning and nerve-shredding film you’ll see this year.”

But even so, I wonder if it would have won such universal acclaim and a stack of Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Screenplay, had it not been a war movie from the perspective of American soldiers? A movie about attitudes to war among Iraqi dissidents would not have sold well on the American home front.

Much is made of the recreation of war conditions, the debris of explosions, the ever-present snipers and IED bombers, the local residents watching soldiers at work, all captured vividly using the prime method of filming war zones using gut-churningly shaky hand-held camera. Veterans carped at some of the combat scenes, though any movie depicting real life will be compromised for dramatic effect, and this is no exception.

Although you might not recognise them in their helmets and in dusty conditions, there is a cast of well-known faces in strong cameo roles here, notably Guy Pearce, Ralph Fiennes and Evangeline Lilly, though it is good to see the leading roles going to lesser-known talent, since using Hurt Locker as a star vehicle would undoubtedly have detracted from the significance of the events portrayed.

Jeremy Renner and Anthony Mackie both come out of the battle with flying colours in difficult roles – Renner as sergeant first class and technical specialist William James, who has lost all sense of fear of death, where his colleague and compatriot Sergeant J T Sanborn (Mackie) is increasingly nervous and on edge with the smell of death all pervading. Where James is addicted by the theatre of war, Sanborn’s nerves are shattered – he for one wants to return home, especially after seeing the death of an innocent Iraqi, to whom a web of explosives have been strapped and chained. James shows a softer side only when hunting out a local boy known only as “Beckham” who he feared had died.

The contrast between the two men gives the movie its dramatic and moral edge, depicting a war beyond reason. Survival is of the fittest, though you expect right to the final scene that James will die in the inevitable IED blast, whether now or some point in the future. His unit, we are told, has a further 365 day mission, which brings to my mind an echo of Joseph Heller’s classic Catch-22:

“There was only one catch and that was Catch-22, which specified that a concern for one’s safety in the face of dangers that were real and immediate was the process of a rational mind. Orr was crazy and could be grounded. All he had to do was ask; and as soon as he did, he would no longer be crazy and would have to fly more missions. Orr would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he were sane he had to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to; but if he didn’t want to he was sane and had to. Yossarian was moved very deeply by the absolute simplicity of this clause of Catch-22 and let out a respectful whistle.”

But where Catch-22 is decidedly satirical, Hurt Locker is deadly serious, perhaps mindful of how real life has overtaken satire with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The movie takes a neutral view, not disagreeing with the American mission as such, but portraying the madness and asking what it is that would make anyone want to be there, whether or not their role is justifiable.

Bigelow has made a movie that is technically inspired, tough and harrowing to experience, but does not exploit to the full the moral decay brought about by war. At heart, The Hurt Locker is more a jangling slice of action, and that would be how the primary target audience would view the movie. How many viewers even questioned the nature of war or if it is right to send men to such an environment is not recorded, though you’d hope some went home with a shades of grey where once they saw things solely in black and white.