“You know the funny thing is, on the outside I was an honest man. Straight as an arrow. I had to come to prison to become a crook.” – Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins)

A good friend mentioned recently that she had not seen The Shawshank Redemption, a fact that surprised me greatly. Surely everyone of the “middle aged” cohort has seen, and probably loved this prison escape drama? Apparently not!

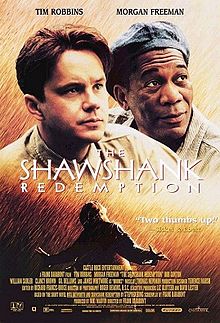

But then it’s a movie that surprised many – one of those rare creatures, a film damned with faint praise by some critics, but which became by virtue of footfall and audience response not just a cult hit but a global smash. In other words, it was a movie which caught the public imagination and took the industry by surprise. The seven Oscar nominations (it won none, though BAFTAs and Golden Globes were awarded) were certainly in part a product of people power, though the provenance of a Stephen King short story and a fine cast including respected figures like Morgan Freeman and Tim Robbins certainly helped.

So why the surprise? Maybe the feeling was that this was just too slow-moving a tale, a prison-based soap opera. Anyone thinking that would of course have missed the fact that the movie preaches the benefits of community and comradeship, patience, and above all that revenge is a dish not only best served cold but nurtured and cherished over decades of planning. No, much more than that – this is an inspirational movie, a tear-jerker in the final analysis, the sort which is so often described as “life-affirming.” If ever I found out what that means I’ll be sure to let you know, though I’m assuming this means it restores our collective faith in humanity.

This is a story that belies its roots. The King short story is about a man wrongly convicted of murder, who eventually uses his cunning to make good an escape, initially given a lukewarm if not sniffy reception by the critics, yet becoming a firm audience favourite and a cult classic – not even that, a movie on many people’s top 10 of all time. A very unlikely case of movie defying the odds, yet by the democratising effect of public opinion the critics were proved wrong and had at length to eat humble pie by reassessing their verdicts in a more favourable light

Despite the slightness of its source material, the Shawshank Redemption is given a full 142 minutes on screen to develop and mature its characters at length. The narrative is not rushed, but it is well-told by a combination of anecdotes and narrative. Its inherent charm lets the audience into the characters and makes us want to know more, the irony being that we can find these inmates sympathetic.

An honest, straightforward, professional family man, an accountant, whom we believe to be innocent is convicted of killing his wife and her lover. Leaving aside the quip that all accountants are guilty of something, we follow Dufresne into the harsh regime of Shawshank State Penitentiary under the evil and corrupt god-botherer, Warden Samuel Norton (the excellent Bob Gunton), how he finds his way, survives the rape assaults of the “sisters,” earns respect among both inmates and wardens alike, runs the library but eventually comes to work on the warden’s accounts, and eventually escapes, turning the knife in the wound for Warden Norton in the process.

The story is narrated by Freeman’s Ellis “Red” Redding, who befriends and assists Andy, who becomes over the passage of time the hero’s best friend and conspirator. The development of their relationship beyond prison buddy becomes the principle focus of the movie, right the way up to their being reunited on a beach in Mexico as the camera soars away into the nether distance. Freeman is reliable as ever, the sassy black version of Robert de Niro, well-matched with Robbins’ Dufresne.

There are plenty of satisfying moments en route, not least with Dufresne playing an aria from The Marriage of Figaro over loudspeakers to the prison population, thus enraging the warden and prison officers, and the final humiliation of the ruthless and corrupt warden.

Dufresne effects his escape by burrowing through the cell wall with a tiny rock hammer, covered by posters of Rita Hayworth, and later Marilyn Monroe and finally Raquel Welch, then into a sewage pipe and out into the real world – and we are there with him every step of the way. Maybe this moral paradox gave studio bosses cold feet, though there is no doubt that dramatically Dufresne is a hero, not an anti-hero. He seeks justice and retribution based on his suffering and the wrongdoing of others, and as the quote at the top reveals, he only learns to break the law to enact his revenge from the experience of being in prison. A neat twist indeed.

Ah, but he does not forget his comrades in arms. Before departing, Dufresne also plants the resources and information to allow Red, eventually paroled after serving an absurd 40 years in chokey, to join him in Mexico, so the movie ends with the splendid reunion and barely a dry eye in the house, nothing less than you would expect from Hollywood.

The weaknesses of Shawshank are for the most part self-evident, notwithstanding those mentioned above. Most obvious is that the inmates, who have lived and worked, cried and laughed together over nearly 30 years of incarceration. Andy Dufresne contrives to finish just as fresh as he started, in spite of the passing of 20-odd years – I wonder what his secret is? Not realistic, but more to the point the passage of years is critical to the success of the narrative and the message of the movie, so writer and director Frank Darabont could have made more of an effort to make his cast look less pretty and less mobile with age.

The assembled players do justice to what could in lesser hands turn out to be cardboard characters, though some fly dangerously close to the wind with the more stereotypical cutouts, notably the rapists. You could also point to the inclusion of many character stereotypes as a dramatic device: the innocent man, the fixer , the institutionalised old lag (Brooks Hatlen, who fails to make the transition beyond prison into the real world), the violent rapists, the brutal guard, the young hopeful and several more. That they are more than two-dimensional cardboard cutouts is credit to the ensemble performances, though there is a sense of the goodfellas here, little recognition of the terrible acts that saw them imprisoned in the first place.

However, what makes Shawshank work as a drama is both the interaction between the characters and the chemistry between them, the sense of community they develop. This does indeed demonstrate that being in prison does not prevent life from being conducted in a civilised fashion, nor that being jailed strips from you your essential humanity. Indeed, you could argue that Shawshank prison is a microcosm of all human life, a metaphor for the chains that bind us all.

No doubt this movie will eventually be discussed and analysed on film-making degrees and other august forums, though in my opinion it is not yet ready to be canonised as a cinematic classic. There are excellent reviews praising it (see here), but for all the humanity I think it needs to mature a little longer in order to be reviewed in full context.

This is not great cinema, but it does push the right audience buttons at the right time, certainly for many a tearjerker as Dufresne escapes. That is to the credit of Darabont’s screenplay and direction. It deserves plaudits for lifting a simple story beyond its genre and making it work as a very full-length movie. But the simplicity of its moral message is also its greatest weakness. More shades of grey would made for a more sophisticated movie, but this one knows its audience well. When you hit the spot, you have a hit on your hands.

Shawshank Redemption does fall prey to a number of prison drama stereotypes, but ultimately wins out by virtue of enabling the audience to empathise with the characters and believe in the redemption of the title. Never underestimate the power of a good redemption, not to mention the power of common decency!

Really liked this review.An older friend of mine told me that Casablanca got a similar muted response when it was first shown but similarly grew & grew. Mark Kermode reckons it’s a religous allegory , I can see what he’s saying because the final dream like scene appears to suggest heaven or paradise ? After all the bad times suffering there is final redemption. I see what you say about the ageing process of the characters in the film but the first time I saw it I was so engrossed on the story I didn’t notice, until further views. What I like about you reviews are that you allow the reader to think about the movie for themself, whilst giving your own opinion and making it all enclusive. When I read reviews in the papers they seem to talk at me not with me. You Sir show respect for your reader it feels like there is an equality between writer and reader.Thanks for this and well done

Thank you kindly! Just wish somebody would pay me for them lol!!

Sorry for spelling errors meant to say inclusive