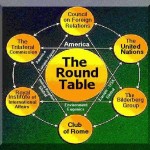

This is a blog about secrecy at all levels, but since we all have secrets this is mostly about those who keep secrets and decide what, if anything, the rest of us should know. It’s been a subject on my mind for some while, given that my current novel centres on the activities of a highly secretive fictional debating society. This week we hear much about the Bilderberg Group, a cabal of business, financial, academic and political leaders who meet at intervals in secret, and to which our PM was apparently invited.

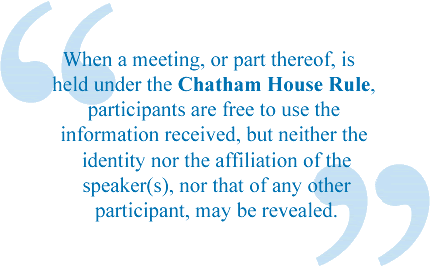

The paradox is that their current conference at the Grove Hotel, Watford, is highly open about its presence, mostly very secretive about attendees, and completely silent about the nature of its discussions, beyond headlines. The reason for the silence is that Chatham House rules apply, namely:

Meetings may be held ‘on the record’ or under ‘the Chatham House Rule’. In the latter case, it may be agreed with the speaker(s) that it would be conducive to free discussion that a given meeting, or part thereof, should be strictly private.

It should be noted when any Continuity Forum meeting, event, or debate (or part thereof) is held under the Chatham House Rule, participants are free to use the information or opinions disclosed to them, subject to two conditions.

(a) Neither the identity or the affiliation of the speakers, nor that of any other participant at that meeting may be revealed, the Continuity Forum will not do so and all attendees are required to maintain confidentiality and discretion.

(b) It may not be divulged that the information was received at that meeting.

While primarily an Honour Rule it should be clearly understood that failure to follow the rule within the confines of Continuity Forum Meetings WILL result in the exclusion of the guilty party from all subsequent meetings.

Where an associated meeting report, briefing or other similar material is to be produced the Continuity Forum warrants that no identification of speakers, delegates or guests will be made to any organisation outside of those actually attending in person. Further, the Continuity Forum warrants no information or other identifying content that could reasonably contribute to the identification of any party contributing will be included in said materials.

Whether or not this is a clandestine group creating a New World Order above the heads of any government or people, and there are many who would hold with that conspiracy theory, by keeping the results of such discussions, and particularly their impact on how we are governed and manipulated, secret, gives rise to suspicion. It may be an entirely benevolent organisation for all we know, but the fact that the richest and most powerful get together behind closed doors is inherently against our interests.

The rationale for holding such meetings in secret is simple: it is believed that if minutes were taken and circulated, attendees would be reluctant to talk honestly and openly on the agenda items, since their private thoughts may well conflict with their public position. Open comments are therefore restricted to what people want to hear, or what is deemed to be in the public interest to know, possibly through damage limitation.

Taking politics as a primary example, politicians never tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth because their goal is to be re-elected. Small wonder we don’t believe them when what they say is essentially contained in a wrapper of naked self-interest.

There is a contention that “open government” is a contradiction in terms too, since the very nature of decision-making has to be taken in secret, and if the decision-making process were truly open the real discussions would be driven underground – whispered conferences in the corridors, over drinks, in the Gents’ loo, anywhere but in the proper fora. Worse, it is argued that any decision made in public will be flawed and compromised.

The flipside is that the “stakeholders” on the outside of the decision-making process, be they voters, ordinary shareholders or anybody impacted by these decisions, have decisions imposed on them without accountability or any opportunity to protest. If they do so, it is retrospective and thereby too late to change what is a fait accompli. Decisions taken are often taken on the basis of what suits the minority clique, not the wider population.

As I’ve said before, democracy and/or accountability – is, or should be a continuous process, not restricted to general elections every 5 years or annual shareholder meetings. Even if our representatives in any nation, society, group, company or other organisation are elected as just that – representatives – they are entrusted to make the right decisions for the right reasons, and to set out the debate and criteria in advance. But in my opinion we are closer to an “elected autocracy” with powers held to keep from us much of what we deserve to know, and with decisions made without any democratic or accountable oversight.

In politics, you might argue that manifestos are just such a document, except governments are not held up to account on that basis: pledges are quietly forgotten, and many more decisions known to be unpopular are quietly forgotten and enacted secretly once the election is won. The hugely damaging and unpopular Health and Social Care act is a prime example of legislation implemented by stealth. Had this bill been included in manifestos, voting decisions for a substantial proportion of the electorate may well have changed.

Ah, but secrecy is embedded at the very heart of the state. We have state secrets and classified information, protected by the Official Secrets Act, which ensures those entrusted with information deemed by somebody to be secret (which I would maintain is regarded as the default position until proven otherwise.) Sensitive information is for these purposes defined by Wikipedia as:

Information sensitivity is the control of access to information or knowledge that might result in loss of an advantage or level of security if disclosed to others.

And the powers that be conduct covert operations to protect us based on covert intelligence information, on the assumption that such information would benefit our “enemies” – a flexible concept and often a catch-all to hide anything which may be awkward if exposed in the press.

Supposedly, this takes place within a straightjacket of legislative accountability, though allegedly this minor technicality can be overcome by using secret American intelligence information spying on the activities of British citizens, according to a source speaking to the Guardian. Our esteemed Foreign Secretary denies – so it must be true!! But then, to amend the words of Mandy Rice-Davies in the heady days of the Profumo scandal, he would deny it, wouldn’t he? Jim Hacker from Yes Minister:

“First rule in politics: never believe anything until it’s officially denied.”

Put simply, I have no faith that the lack of transparency over the operation of intelligence can give us any confidence in what they do or how they do it. Richard Helms, once Director of the CIA, famously said: “We are honourable men. You simply have to trust us.” Well I demur – I have no faith whatever that the people concerned are acting in the best interests of myself or the world, unless or until proven otherwise.

Having committees of MPs occasionally keeping an eye on the activities of secret services gives me no confidence whatever, let alone permitting freedom of speech to provide public scrutiny of what is done in our name. And if I were American I would be even more concerned that PRISM gives the American security and intelligence services carte blanche to listen in to anyone in any country outside the USA and monitor their computer activities. From the standpoint of the American president this is legal, above board and approved by Congress; from the perspective of any decent citizen of the world it is a snooper’s charter which ignores entirely all human rights to privacy and freedom of speech.

As whistleblower Edward Snowden said in his interview with the Guardian:

“The government has granted itself power it is not entitled to. There is no public oversight. The result is people like myself have the latitude to go further than they are allowed to,”

Who do you trust? Well clearly not politicians or anyone in “The Establishment” since they will not ever give you the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. You will only ever be told what is deemed a story fit to print, unless and until the truth comes out, which, depending on the nature of the information, may be released under the 30 year rule or up to 100 years, depending on the nature of the information. In practice, some of the information deemed worthy of protection is so laughable you see the serious side – that the people who decide what should be classified cannot be trusted either.

Remember Julian Assange and the Wikileaks debacle? Assange is still holed up in the cramped conditions of the Ecuadorian embassy in London. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the charges against him, which may or may not be trumped up, there is no doubt the US government wishes Assange and Wikileaks to be silenced, though I and many other think that throwing light on to the activities of government is precisely the best way to achieve transparency and to improve the likelihood that peace and human rights can be maintained.

Of course, if deemed to be in the interests of the people at the top of the tree (usually politicians), somehow this information does leech out into the public domain, though everyone always denies leaking. This reminds me of the great quote by Bernard Woolley, also from Yes Minister:

“Oh, that’s another of those irregular verbs, isn’t it? I give confidential press briefings; you leak; he’s been charged under Section 2a of the Official Secrets Act.”

I often suspect that the British voting public are deemed the real enemies of those in positions of authority, not the Russians, North Koreans, Al Queda or anyone else. There are many things we as citizens are not allowed to know, despite our Freedom of Information Act (FoIA.) Even this striptease of a piece of legislation has a whole host of exceptions, which seem to be growing by the year as government finds FoIA increasingly inconvenient. The following were built into the original Act in 2000, the sheer volume and vagueness of which tell you any piece of information which someone doesn’t want in the public eye will never be released:

Although the Act covers a wide range of government information, the act contains a variety of provisions that provide for the exemption from disclosure of certain types of information. The act contains two forms of exemption. “Absolute” exemptions that are not subject to any public interest assessment, they act as absolute bars to the disclosure of information and “qualified” exemptions where a public interest test must be made, balancing the public interest in maintaining the exemption against the public interest in disclosing the information. The original government white paper on the freedom of information act proposed only seven such exemptions, but the final bill included 24.

Absolute exemptions

Exemptions designated “absolute exemptions” have no public interest test attached, the act contains eight such exemptions:

- Information that is accessible by other means (s.21)

- Information relating to or dealing with security matters (s.23)

- Information contained in court records (s.32)

- Where disclosure of the information would infringe parliamentary privilege (s.34)

- Information held by the House of Commons or the House of Lords, where disclosure would prejudice the effective conduct of public affairs (s.36). (Information that is not held by the Commons or Lords falling under s.36 is subject to the public interest test)

- Information which (a) the applicant could obtain under the Data Protection Act 1998; or (b) where release would breach the data protection principles. (s.40)

- Information provided in confidence (s.41)

- When disclosing the information is prohibited by an enactment; incompatible with an EU obligation; or would commit a contempt of court (s.44)

Qualified exemptions

If information falls within a qualified exemption, it must be subject to a public interest test. Thus, a decision on the application of a qualified exemption operates in two stages. First, a public authority must determine whether or not information is covered by an exemption and then, even if it is covered, the authority must disclose the information unless the application of a public interest test indicated that the public interest favours non-disclosure.

Qualified exemptions can be sub-divided into two further categories: class-based exemptions covering information in particular classes, and harm-based exemptions covering situation where disclosure of information would be liable to cause harm.

Class-based exemptions

- Information intended for future publication (s.22)

- Information which does not fall within s. 23(1) is exempt if required for the purpose of safeguarding national security (s.24)

- Information held for purposes of investigations and proceedings conducted by public authorities (s.30)

- Information relating to the formation of government policy, ministerial communications, advice from government legal officers, and the operation of any ministerial private office (s.35)

- Information that relates to communications with members of the Royal family, and conferring honours (s.37)

- Prevents overlap between FoI Act and regulations requiring disclosure of environmental information (s.39)

- Information covered by professional legal privilege (s.42)

- Trade secrets (s.43(1))

Harm-based exemptions

Under these exemptions the exemption applies (subject to the public interest test) if complying with the duty under s.1 would or would be likely to:

- Prejudice defence or the capability, effectiveness or security of any relevant forces (s.26)

- Prejudice international relations (s.27)

- Prejudice relations between any administration in the United Kingdom and any other such administration (s.28)

- Prejudice the economic interests of the UK (s.29)

- Prejudice law enforcement (e.g., prevention of crime or administration of justice, etc.) (s.31)

- Prejudice the auditing functions of any public authorities (s.33)

- In the reasonable opinion of a qualified person: prejudice the effective conduct of public affairs; prejudice collective responsibility; or inhibit the free and frank provision of advice or exchange of views (s.36)

- Endanger physical or mental health, or endanger the safety of the individual (s.38)

- Prejudice commercial interests (s.43(2))

While FoIA disclosures have brought to light things almost any government would find embarrassing and would attempt to hide until rumbled, in many ways the codification of such rules also makes it easier for a vast array of information to be classified in such a way that it is never made public until much too late for anyone to do anything about it. I’d argue that all information should be in the public domain, for better or worse. But no, it’s censored, spun, bits are hidden or disguised. There is a whole industry behind the masking of disclosures.

I’m reminded of the words of Sophocles:

“Do nothing secretly; for Time sees and hears all things, and discloses all.”

Alas, time may work too slowly for the secrets and scandals of society to be brought to the public attention and for perpetrators to be punished. One prime example is the Hillsborough tragedy, a mere 24 years ago yet the truth of the conspiracy designed to protect the reputation of West Yorkshire police by blaming the fans took most of that time to come to light, by which time the senior officers concerned have retired or died and will never be brought to justice. Secrecy wins out, much in the same way that Jimmy Savile successfully hid the truth about his abuse of children for decades, and was believed.

The point is this: it does not need to be a scandal, but unless the people impacted directly or indirectly are given the full facts in order to make up their own minds, how do we truly know whether the decisions taken are in our interests or not? I can’t speak of whether our “national secrets” should be secret, since nobody tells me what they are, but looking at examples that have come into the public domain over time I’d say many classified secrets are not secret for any good reason, only that they would cause embarrassment. And frankly if it is not the role of press and public to cause government and state embarrassment for its cock-ups we would all live in a police state.

Maybe we should all set a good example by being more honest and open about every aspect of our lives, not keeping silent about things which, in some contexts, might be deemed embarrassing? Some might talk about their sex lives but to many more such talk is vulgar and undesirable, though if we all did communication within relationships might be far better.

My decision to talk openly about some things men traditionally hide actually won me plaudits: my blog about my history of depression, and my decision to get tested for prostate cancer (negative.) Why would I have anything to hide in either case? Not like either will harm my career, relationships or anything. The benefit was that many more people felt emboldened to talk about both subjects and to seek help. If we all started from the presumption that there is nothing to hide and that our behaviour is human, maybe it would benefit everyone, so long as we discussed it at the appropriate time.

Ah, but we are not going to advertise if we have ever broken the law. Speeding and parking offences notwithstanding, we would not boast of any incident that could land us in court, or indeed if we have been locked up in clink – unless we are rehabilitated and arguing against such an offence. Strangely, openness reduces the tendency towards a seamy side of life, that of which nobody speaks. Victorian society is often spoken of as the time when the contrast between public morality and private sin was at its sharpest, though maybe we are just more sophisticated about covering our tracks nowadays?

We, like governments and the boards of public companies, tend to operate a PR policy which puts us in the best light. We can’t help it, we just do. Would things change at the top if we set a good personal example?

Probably not, since those who have climbed the greasy pole would undoubtedly have too much to lose. Would that we had the ability to elect those who would be open and candid, though I suspect they would all cling to the belief that knowledge is power, and that once they know they possess it and are thereby more important.

Not so. As students of Knowledge Management know well, sharing knowledge and collaborating for the good of all is far and away the most powerful and innovative to exploit information. When we have true transparency as a society, I will then know we have matured.

Let’s ask a simpler question: what do we have to hide? Not very much, truth be told.