As of now there are 8 series of the TV drama Dexter, of which I have watched 4 and am half way through the slim DVD set of series 5. The show was based on a novel by Jeff Lindsay called Darkly Dreaming Dexter, though as a TV series it has formed its own life, defined by Wikipedia as fitting into the various genres of crime drama, suspense, psychological thriller and black comedy. In truth Dexter found its own highly successful and formulaic niche and has worked this with admirable effectiveness, much as was achieved by, say, House.

Added to the pot are the city of Miami, its Hispanic community and, especially, the central conceit on which the plots are developed (see below for this one – there is always a concept with a twist at the core of every new TV drama series), but from the moment the gorgeous opening theme music begins to when the closing music ends there is much to entice you into this addictive melting pot and keep you hooked. The opening titles are effective, suggesting the normality of Dexter’s life, overlaid by the violence he perpetrates when no-one is looking. But then serial killers don’t generally advertise their passion since they don’t want the addiction to be curtailed.

Dexter Morgan is a police blood spatter pattern analyst is by night a serial killer, but one who chooses his victims through the lens of moral integrity. His scruples were taught by his late adopted father Harry Morgan, a police officer not averse to killing low-life murderous scum.

The late Harry Morgan appears at regular intervals as a dramatic device; he is Dexter’s conscience much as Jiminy Cricket is the conscience of Pinochio. Harry’s purpose is to remind Dexter of “the code” (the first and most important item of which is “don’t get caught”), much as Ed Gein does in Hitchcock.

The code will also not allow him to kill anyone who does not deserve to die, by virtue of the harm they do to other people without being picked up by the police. In short, he needs strong evidence of their guilt, while falling below the standard of proof demanded by the legal system. We, the audience, are in the know but other characters are in varying degrees of ignorance about the reality, not least Dexter’s sister, girlfriend-turned-wife, boss and colleagues.

The drama turns on his addiction to killing, Miami murders and the risks Dexter takes with the ever-present risk of exposure, though his modus operandi is well rehearsed to minimise risk, with minute attention to detail. Even Dexter makes mistakes though, and if he didn’t there wouldn’t be too much to sustain our interest. However, one smart move is his tendency to assume a dumb countenance when compared to his cop colleagues on the force, assisting his anonymity in the same way the bumbling Clarke Kent does for Superman.

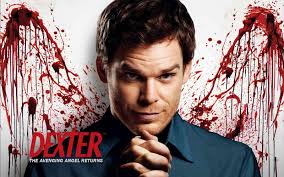

The success of the show is due in no small measure to the many talents of Michael C Hall, an actor you may remember from the excellent Six Feet Under. Hall is a likeably cheeky performer, irresistibly charismatic and charming in equal measure (though he is also responsible as co-executive producer for Showtime.)

That Hall’s character has a dark side and that his form of morality is deeply corrupted works well. Dexter would not be anything like as effective without his alter ego, though the various plots and subplots, woven around the various characters, keep the pot boiling – include his real-life wife (up to 2011), Jennifer Carpenter, playing sister Debra. From time to time colleagues are sufficiently bright to work out there is more to Dexter than meets the eye, so foxing them is another weapon in the Dexter armoury, or more accurately another pesky issue on his tasklist to be managed.

Equally vital are the villains, of whom there are a fascinating assortment. My favourite by far is the wonderfully menacing John Lithgow as the “Trinity Killer” in series 4. Just as the aforementioned Superman must have their equal counterpoints, so must Dexter. If the game of chess played out between the protagonist and his nemesis is not sufficiently engaging, the entire drama would collapse like an ill-timed soufflé, but thankfully most of the characters – and actors playing the characters – have been excellent. The baddie is always the best role for an actor, but these days the hero is also morally ambiguous, though even the FBI are baddies of a different sort.

Dexter relies for its shock and awe on liberal quantities of splattered gore and the display of corpses in various states of decomposition and dismemberment. Such is life for a forensic officer in Miami, though equally this demonstrates the nerve of Showtime in knowing that for every squeamish audience member repulsed by the sight of blood, there will be many more attracted and sustained to keep the series going until the variations on murder and detection have been exhausted and the formula begins to repeat itself. Its language is in keeping with the Sopranos tradition for post-watershed adult dramas, which is to say earthy and fully explicit.

If you had to pinpoint the failings of the show, they are the flipside of its success: it sticks rigidly to the formula and never deviates too far, so the scriptwriters and plotters have a big task to keep the action flowing through interweaving plots and subplots that stick close to the established pattern. They manage this with distinction, enabling Dexter to escape from tricky situations cleverly, as heroes often do. There is just such an instance in series 5, involving very large warehouses, a woman trying to kill a man who raped her but who is a very bad shot, Dexter, a man wrapped in cling film in the boot of his car and the Homicide squad. Enjoy!

Which leads me neatly to point two, namely that Dexter is typical of quite a number of TV crime dramas; like pulp fiction, they are easy and quick to consume and discard, and contain little content that is likely to attract you back for multiple viewings. It’s cool but it lacks depth, and insights into the work of the serial killer won’t sustain you. The episodes are what they are, and what they are is well done but, in Frank Lloyd Wright‘s memorable phrase, said of TV in general, “chewing gum for the eyes.”

As with all formulaic dramas, you know Dexter will ultimately triumph against adversity and neat plot twists, albeit a little tarnished, and there will be a perverse moral to the tale. This contrasts slightly with House where, for example, the character went at various times into rehab and into prison, and while he usually saves patients he breaks every ethical page in the book; Dexter disposes of his subjects, usually in Miami Bay.

But then, since I am several series behind, there may be greater risks taken yet. Watch this space!