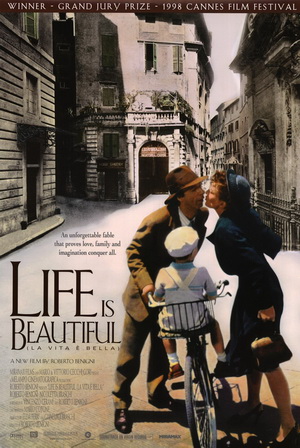

Another review coming out of my recent list, Movies That Made Me Cry, for which I provided the following potted review:

Roberto Benigni’s movie turns from knockabout comedy to a moving tribute to his character’s father, who sacrificed his own life in a concentration camp to save his son.

In truth I’m not sure whether to classify this as a comedy, a drama or a classic, though you could make a case for all three. I’ll pick drama because, in the final analysis, the legacy of Life is Beautiful is dramatic without ever becoming melodramatic.

Benigni came out of Italian theatre, television, left wing politics, acting in movies by Bertolucci, Jarmusch, Edwards and Fellini while making his own name on the big screen as director and performer. There is no doubt that making La Vita è Bella (Life is Beautiful) in 1997 was the highlight of Benigni’s career, catapulting him from the Italian market into international stardom. The movie won three Oscars, including Best Actor for Benigni – a very rare feat at the Academy Awards, matched only once in my memory, by Marion Cotillard for her astonishing performance in La Vie En Rose.

In this case, it is a tragi-comedy in Italian that captured the attention of the world. Not very promising as a starting point to capture the subtitle-averse American market, you might think. Benigni achieved this masterstroke by making two films in one: a knockabout comedy in the finest American tradition, charming the socks off the audience in the process; and then when they have grown to love the character, socking them on the jaw with pathos that would leave not a single dry eye in the house.

The first half is a romcom with a harder edge, one familiar to anyone who has watched, say, Cabaret with the growing scourge of Nazidom. Guido, the Jewish waiter, pursues Dora, the uptown girl, with charm and vigour, until in the end she rides away with him into domestic bliss. At least, up to the point where the fascists intervene. Courtesy of Wikipedia:

In 1939 Italy, Guido Orefice is a funny and charismatic young Jewish man looking for work in a city. He falls in love with a local school teacher, Dora, who is to be engaged to a rich but arrogant civil servant. Guido engineers further meetings with her, seizing on coincidental incidents to declare his affection for her, and finally wins her over. He steals her from her engagement party on a horse, humiliating her fiance and mother. Soon they are married and have a son, Joshua.

Through the first part, the film depicts the changing political climate in Italy: Guido frequently imitates members of the National Fascist Party, skewering their racist logic and pseudoscientific reasoning (at one point, jumping onto a table to demonstrate his “perfect Aryan bellybutton”). However, the growing Fascist wave is also evident: the horse Guido steals Dora away on has been painted green and covered in antisemitic insults.

And then… they are gone, taken from their home. The depiction of the man protecting his son in a concentration camp through absurdist humour is beautifully done, but ends with the father sacrificing his own life so his son may survive. Most parents would say they would give their lives to protect their children, but to see it done in this way is heart-rending.

Later during World War II, after Dora and her mother have reconciled, Guido, his Uncle Eliseo and Joshua are seized on Joshua’s birthday, forced onto a train and taken to a concentration camp. Despite being a non-Jew, Dora demands to be on the same train to join her family. In the camp, Guido hides their true situation from his son, convincing him that the camp is a complicated game in which Joshua must perform the tasks Guido gives him, earning him points; the first team to reach one thousand points will win a tank. He tells him that if he cries, complains that he wants his mother, or says that he is hungry, he will lose points, while quiet boys who hide from the camp guards earn extra points.

Guido uses this game to explain features of the concentration camp that would otherwise be scary for a young child: the guards are mean only because they want the tank for themselves; the dwindling numbers of children (who are being killed by the camp guards) are only hiding in order to score more points than Joshua so they can win the game. He puts off Joshua’s requests to end the game and return home by convincing him that they are in the lead for the tank, and need only wait a short while before they can return home with their tank. Despite being surrounded by the misery, sickness, and death at the camp, Joshua does not question this fiction because of his father’s convincing performance and his own innocence.

Guido maintains this story right until the end when, in the chaos of shutting down the camp as the Americans approach, he tells his son to stay in a sweatbox until everybody has left, this being the final competition before the tank is his. Guido tries to find Dora, but is caught by a soldier. As he is marched off to be executed, he maintains the fiction of the game by deliberately marching in an exaggerated goose-step as he passes Joshua’s hiding place.

The next morning, Joshua emerges from the sweatbox as the camp is occupied by an American armored division; he thinks he has won the game. The soldiers let him ride in the tank until, later that day, he sees Dora in the crowd of people streaming home from the camp. In the film, Joshua is a young boy; however, both the beginning and ending of the film are narrated by an older Joshua recalling his father’s story of sacrifice for his family.

Indeed, the closing narrative of the movie are the words spoken by Joshua on the soundtrack as he is taken to safety by American soldiers:

“This is my story. This is the sacrifice my father made. This was his gift to me.”

Truth be told, the movie could have failed to deliver its knockout punch in lesser hands than Benigni’s. To pull off this feat requires rare skill, especially when you consider the self-consciously “old-fashioned” style of acting and direction, a deliberately retro slapstick style with nods to many of the great comic actor-directors, right back to Chaplin and Tati. Benigni is a clown in the same tradition, capable of finer, subtler performance without excess emoting.

You could count on the fingers of one hand directors who could achieve the right balance achieved by Benigni in Life is Beautiful, but the fact that it was made in Italy by Italians, away from the dead hand of Hollywood makes a crucial difference. Imagine an American version of this movie: it would be ladling on sentimentality in nauseating quantities, but more to the point it would not have been made in its existing plot.

Why? Because Hollywood would not dare to include humour in close juxtaposition to the horrors of the concentration camp, notably the moment when Guido takes a turning in the fog and finds a huge pile of Jewish bodies waiting for disposal. It is a shocking moment, and to me the contrast with the ridiculous story maintained by Guido for Joshua’s benefit makes it all the more horrific. Studios would simply reject any attempt to put the two side by side, not least in deference to the American Jewish lobby.

The script, co-written by Benigni and Vincenzo Cerami, helps enormously, even in translation. It is fizzing with invention. Sparkling dialogue is everywhere to be heard, a few examples of which are to be found here. The ensemble performances do justice to the script too, not something you could say of every such movie. Having one person to write, direct and act could be a recipe for unmitigated disaster, but here it works to such brilliant effect you can see how any external pressure would have diluted the final impact.

Question is whether Benigni can ever again match the impact of this movie, or whether making smaller-scale productions in Italy for Italians will mark the remainder of his career. But then if you can use the reputation you created from such a moment to engender an audience for one-man shows and improvisational poetry, good luck to you!