“It doesn’t matter what I feel. It doesn’t matter what I think. The dead stay dead” – Hanna Smitz in The Reader

There are many things to admire about Stephen Daldry‘s sober and effective adaptation of Bernhard Schlink‘s novel The Reader. Chief among these are David Hare‘s script and the acting, of which more shortly.

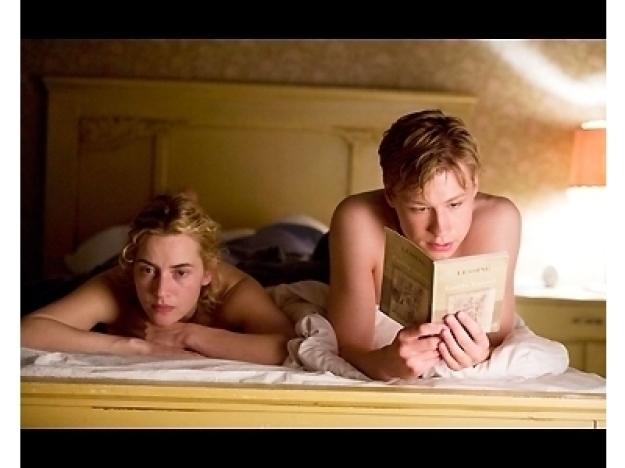

On the face of it, this is a simple tale, the history of an affair between Hanna Schmitz, a 36-year old woman (Kate Winslet) and Michael Berg, a 15 year old boy (played by David Kross as a teenager and in older years Ralph Fiennes.) It leads on Michael’s surprise discovery of Hanna trial for being an SS guard at Auschwitz while he is a student of law, his realisation about why she did not admit a personal truth that would at least have greatly reduced her prison sentence, and the impact of their later meeting. But there is a strong undercurrent of debate about the relative morality, and a subtle and unspoken quality to the relationship between the two, always a notable sign of a very fine movie.

Each phase of the movie is made beautifully: the affair is erotic and sensitive; the trial and its denouement are on a knife edge; and the more complex feelings that wrap up the ending leave a lasting legacy in the mind of the viewer. Whether Hanna’s control over the young Michael is indicative that she was more guilty than she let on is not clear, but the pivot of the plot is when she admits she wrote a damning list of prisoners to be executed in a burning church rather than own up to her own illiteracy.

Some have argued that counterpoint trivialises or attempts to excuse the death for which she and the other guards (who gang up to blame her for the murder of 300 Jewish victims in a fire), though this is counterbalanced by Michael’s refusal to see her during the trial and force her to admit her failing. By so doing he ensures she is jailed for life, about which she apparently does not care, still less to defend herself other than in terms of doing the job for which she was employed. Is the character merely doing her job, too simple to understand the significance of the charges against her, easy for the fellow guards to treat as a scapegoat?

So to the acting, but before I go on I do need to admit what may be a personal bias, though I suspect I am not alone in this. Winslet, Fiennes, Kross and every other actor are exemplary in every way, but for me Bruno Ganz towers over each and every scene in which he appears – much as he does in pretty much every other production with which he is associated. His Hitler in Downfall was a truly staggering performance, arguably the most brilliant depiction on film of any historic character.

Here his role as a Professor Rohl at the University of Heidelberg would in the hands of most actors have been a humble cameo with a performance telephoned in during negotiations for a starring role with his agent, but such is the charisma of Ganz the character is mesmerising, even when saying little. He is both an arbiter and a catalyst, judge and jury. Were I ever to direct a movie requiring a mature actor, Ganz would be first on my list.

But Winslet it was who won the Oscar, as Best Actress for playing Hanna. Winslet’s acting employs the best of screen micro-acting, using small gestures and facial expressions to convey meaning. Would that every actor did the same.

This a great accomplishment in a difficult role that requires her to portray many contrasting facets. On one hand the character is relatively innocent and naive (such as in the courtroom), while in the context of a relationship with the innocent Michael she enjoys her dominance. She has him read to her, a request he later learns was also asked of inmates at Auschwitz before she sent them packing to the death chambers. Only later does he realise the significance, though the viewer will long since have clocked why Winslet is behaving in this fashion. She is not quite so convincing as the older Hanna, learning to read from the tapes of books and stories sent to her by Michael, now a leading trial lawyer, but I suspect some distaste of old age would be a reaction to many playing much older than their years.

But overall, I feel this to be a great success, verging on triumph without quite hitting the absolute top notes. The Reader is a movie to be savoured at length, possibly watched two or three times and not treated as instant gratification, despite it’s fairly explicit sexual content (we see a great deal of Kross and Winslet naked and in various clinches, authentic poses for their roles as lovers.)

The content is not necessarily as weighty as some movies of its ilk, but certainly requests its audience to think, in the same way as, for example, American Beauty (directed by Winslet’s ex-husband, Sam Mendes.) Cerebral is no bad thing, and frankly the trend towards more mindless action pics is not a positive move – unless the aim is to turn cinema audiences into zombies, which is far from impossible. Please, movie industry, can we have more like The Reader, pretty please?