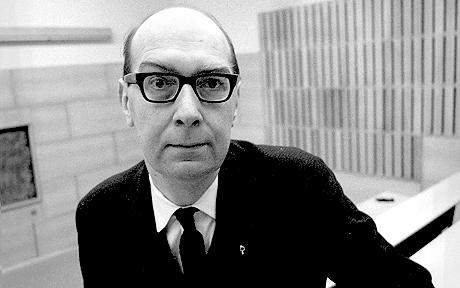

You will recall that the estimable poet, jazz critic, librarian, misogynist and racist, Philip Larkin, referred to work or vocations as Toads in that and another poem. He also lists people who live by their wits:

Lots of folk live on their wits:

Lecturers, lispers,

Losels, loblolly-men, louts-

They don’t end as paupers

…and doubtless many artists, writers and many more too. I’ve written in another blog about Toads and the cliches of office work (in the 2009 blog archive, but reprinted below for convenience), but maybe it is time to explore the topic in greater depth.

Seems to me that for every person who loves their job, vocation and/or career in its own right, a lot more treat it as a means to an end, endure work and live for the end of the day or week so they can go off to enjoy those leisure pursuits which afford some measure of relaxation, “so”, as Tom Lehrer famously put it, “you can forget perhaps for a moment your drab, wretched lives.”

But if there is anything worse than being in work you don’t enjoy, what’s worse is not being in work or having an income stream. Much as we sometimes wish we didn’t have to, earning a living is not an option unless you happen to have a private source of income and/or source of wealth, or you choose to live an alternative lifestyle that requires little if any cash. For most of us, neither of those are feasible options, so work is the best option, or the benefits system if for any reason we can’t work.

Such an inexact science, work. We may well be square pegs in round holes for expediency, not doing those tasks for which we are best suited or around which our dreams were once based, so it would hardly be surprising if most of us lacked serious motivation to go out there and give it our all. While it may have moments of glorious success, perhaps those when we have been praised for efforts by the ascending hierarchy of management, but most of the time our efforts go relatively unacknowledged and with minimal reward. Do our earnings really incentivise us to greater effort?

Strange then to see the debate about the pay of bank traders and senior execs, people who earn high salaries but need higher bonuses to prevent them taking their skills and going elsewhere to work, we are told. I always thought that for your salary you performed to the best of your ability, and if you already earn a huge salary I fail to see how a huger bonus can make a difference to your motivation, but that is how the other half live. If you believe Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, once you have earned enough to pay for the basics of a good living, the value of such a remuneration package is largely in the status it gives you in the pecking order of Chief Execs rather than what you can afford with the cash. If you have three houses and five cars, do you really need any more?

Interestingly, when the debate arose about Stephen Hester‘s bonus as Chief Exec at the now largely publicly owned RBS, the justification for his bonus was related to how hard he has worked. Having worked extensively in retail banking over the years, I don’t doubt that many of Hester’s RBS employees work every bit as hard as he does, and possibly more, but don’t earn a fraction of his salary, let alone bonuses.

For me, I decided long ago that I work to live, not live to work. I’m not motivated by money, providing I can get enough to provide security for me and my family, and to fund my lifestyle, as a man who admittedly likes a number of the finer things in life. However, I do want a sense of achievement. The issue with client work is often that my work does not achieve huge recognition, even if it has played a significant role in the turnaround and success of organisations, but then I don’t expect to be lauded from the rooftops for it. That isn’t why I do it either, however nice it is to be respected for my professional skills and experience once in a while.

So what motivates me? Creativity! Ironic then, with much acknowledgement to Maslow, that I gain write, act and cook without any serious expectation of financial reward. If I did those things to earn a crust, would the enjoyment lapse and blogging become a chore? I doubt that very much, since writing truly fulfils a need in me not satisfied in any other way. Still doesn’t stop the need to earn cash to pay my mortgage, but it’s an essential part of who I am.

At least working for myself gives options not available to those who don’t. Yes, you are still beholden on clients but if you choose not to take on a piece of work nobody will force you… though the bank manager may have something to say if you do it too often. At least my boss lets me do what the hell I like, where mostly incompetent bosses cause lives to be a living hell.

How often do I hear friends say their boss did this or that, and how stupid and inconsiderate or worse they were? Almost daily! I can remember the feeling of leaden doom in the pit of my stomach from getting up in the morning to go to a job that was stressful and/or unrewarding and/or laboriously dull and/or pointless in the extreme. You know what I mean, the sort of job that reminds you of that WWI anthem of British soldiers on the front line: “We’re here because we’re here because we’re here because we’re here.”

But then, maybe that is just bad management. The charismatic leader will surely unite his or her workforce and point them in the right direction. The cliche has it that a TV crew interviewed a cleaner at NASA about what he did. He replied, “I help get people to the moon.” If you can communicate the vision and make even the lowest level of employee embrace the vision, maybe people will try harder, but could it be that this is an illusion which might pop whenever reality intervenes?

That may be one factor, but how often does your employer make you do things you don’t want to do, convey messages you feel are morally unjustified? Sack a loyal employee who depends on their job because they made one mistake, for example? Do you ever rebel, or in these austere times just grit your teeth and get on with it rather than contemplate the market for redundant middle-aged middle managers, for example? A difficult decision, but a wise company will listen to those who offer a reasoned response to a bad strategy. Surrounding yourself with yes-men does not bring success!

But if we do not achieve the position we expected to be in or doing the things that bring us pleasure, is that because we failed to concentrate in school? Or find our true vocation? Arguably Larkin’s vocation as a university librarian both gave him time to write his spare volumes of poetry, but since he chose not to do the international writer’s circuits and do it as a true professional, prevented him from unleashing his imagination further upon our senses.

Toads… or, this working life (July 2009)

Many years ago I worked in a very particular office. Nothing unusual about that – I’ve worked in a great many of them and been miserable as sin in a fair proportion. But this was no ordinary office. Forget Ricky Gervaise and the excrutiating embarrassment of his TV version, this was the original, no holds barred mother and father of all desperately awful working experiences.

You can usually tell the bad signs from the moment you enter such an office. This one looked as if it had not been re-equipped with new furniture since about 1860. The desks were shiny from years of bodies slumped across them, deep grooves and doodles carved by people long since retired, driven no doubt by the sheer intensity of their boredom. The lighting was dim and the venetian blinds covering the window seemed to have been long since glued by a potent combination of sugary tea, dust and sunlight, so that they would not now move in any direction. Dim light came from ancient crackling florescent bulbs hidden way up on a high ceiling and shaded so the room was half in shadow and half bathed in blinding artificial white light.

This being before computers became (a) small and (b) cheap and plentiful, there were precisely two in the office. One was a terminal to a mainframe computer, complete with green screen. The other was an original IBM PC with a command line DOS interface and precisely two applications: a prehistoric version of WordPerfect and a primitive spreadsheet like VisiCalc v1.0, on which accounts were maintained with religious regularity, and printed on enormous dot matrix printer that made the most incredible clattering noise.

But all this was not the reason for my hatred of working in this office. That was just the set. The players shuffled on stage at 8:55am every morning and shuffled off at 4:55pm each day. Not only did they conformed to every known stereotype, but formed lasting cliches in my mind:

There was the barrack-room lawyer, as my dad would have called him. If anyone remembers Arthur Haynes, that was him to a tee – pompous belligerent ex-army type, yet remarkably servile when his boss was anywhere nearby. Yes, he did have a bristling moustache and did smoke a pipe, often in the office. Immediately I treated him with rather more deference than was due, much to his obvious delight, though in fact he was remarkably junior for his age (perhaps early 50s.)

Next there was the spinster, for spinster she undoubtedly was. Possibly in her mid-40s, she spoke wistfully like a 70-year old about spending weekends with her nieces and nephews, and like Miss Haversham wore a permanent expression of noble sacrifice. She was the high-necked priestess, the office oracle. People, largely women, would come to her in a steady stream about everything, be it work, relationships, gardening, making clothes, hairstyles, you name it. She knew every procedure, which form needed to be filled out for which purpose, where you filed the pink, green and yellow copies, who to go to for every possible grievance… yet it was her own life and career that seemed far more on the shelf.

The office junior, Terry, looked and behaved exactly like an awkward teenager in a totally alien environment. He generally wore a pair of baggy brown trousers, a scruffy shirt with one or two buttons open to reveal a vest beneath, and a badly knotted tie of the high school monster variety, sometimes with a tank top in a vile shade of mauve or lime green knitted by his grandmother. You could never engage him in eye-to-eye contact. Conversations were short and painful. If he had a job to do (which usually consisted of processing mail, making tea and filing endless reams of paper), it would be done in a surly and resentful fashion. The only time I saw Terry spring to life was when I inadvertently caught him on the phone (one of those big old grey numbers with a dial and a chunky cord) talking to a mate about football or girls or nights out boozing, whatever it was. But as soon as he saw me, down went the receiver and normal service was resumed.

Then the boss. He (for they were always ‘he’ in those days) had a connecting office with frosted glass. He actually said very little but did periodically come out to talk to Miss Haversham or Arthur Haynes in a gruff tone that sufficed for professional conduct in those days. Even more mysterious, they were occasionally invited into his inner sanctum for deliberations, though nobody ever repeated a word. I was largely ignored, and Terry the Teenager barely warranted so much as a glance.

Occasionally, someone got a roasting. It was the most animated the boss ever got. The victim was invited to sit before his desk while he ranted on in a not unkindly tone, befitting a man who found it utterly painful to hurt another human being, but one which left you feeling an abject failure, the most miserable snivelling creature crawling the earth. Humiliation was called for and humilliation was what you got. If it had been in Japan, the victim would have broken down and shot himself. Here, people studiously ignored it and got on with whatever they were doing. Dressings down were never ever referred to, even though every word could be heard.

So why was all this so miserable for me? I could put up with the tellings off, largely because the boss did not really believe in what he said. But I hated it because it felt DEAD! All life and spirit had been surgically drained from people, the work was tedious and without variety. Fulfilment, satisfaction, enthusiasm – all gone with the wind. The highlights of the day? Lunch (akin to old fashioned school dinners, of the liver and onions followed by steamed pudding and custard ilk), then home time. As TS Eliot put it, “I have measured out my life with coffee spoons”, and in my time in that office clock watching was not just a sport, it was a religious observance.

So it was that I chanced upon Larkin’s poem Toads, and knew that at some point that toad WORK had to gain relevance, and that one day I would be using my wit as a pitchfork. So it is, that I have now worked for myself these past 16+ years, like “lecturers, lispers, losels, loblolly-men (and) louts” I’ve lived by my wits. And it will never be any different, while I still live and breathe.