Recently a boxer called Derek Chisora took his chance in a match against a world champion called Vitaly Klitschko. In the ring, he apparently performed with great credit, losing on points after a brave challenge. Outside the ring he caused controversy by, slapping Klitschko during the weigh-in, spitting at Vitaly’s brother Wladimir in the ring, then having an impromptu brawl in the press conference with another British fighter, Davy Haye. This earned him threats of legal action, indefinite bans and steep fines from one of the boxing authorities, and much opprobrium from the boxing fraternity.

In fact, I listened to a programme on the radio this evening about this very issue, at which there was much wailing and gnashing of teeth about how Chisora had sullied this honourable, nay, noble sport by his actions.

The hypocrisy borders on the ludicrous: a professional sport which consists of men hitting each other about the head in a regulated and licensed way is shocked by a punch-up at a press conference? Time to take a reality check here, guys! Forget for a moment that this is a hyped-up “sport” with at least five rival governing bodies and which behaves like a combination of Jerry Springer and a soap opera, and instead focus on the purpose of the event.

Let’s start with a distinction though: amateur boxing is different to professional. Out of curiosity I booked an evening of Olympic amateur boxing for the summer, which will be the first time I have attended live boxing. Amateur boxing matches consist of three rounds between two people wearing head protection and gloves with white circles. The objective is not to knock the opponent into next week: the boxers are awarded points for contact with the head or body of their opponent, with the points being recorded in real time and open for scrutiny. The winner is clearly evident and in the event that things get rough, the referee breaks up the action. So far as I know, no amateur contest conducted by these rules has ever resulted in brain damage or serious injury.

The professional ring is a totally different beast. Here’s how it started – shamefully and without any honour, nor yet any result. You might say the proliferation of control boards, governing bodies, with the farcical situation that you can have no fewer than four world champions in any one weight division. Fighters win titles, get their belts stripped for choosing to or not to fight the official challenger from one body rather than another, and very rarely do you get an undisputed champion.

Rich promoters create a sham contest to raise pay-per-view TV takings is outrageous enough, certainly not how a truly professional sport should be run, and the apparent concern for safety is largely for show.

The rules might have moved on since the early days days, but there are still many myths from which the observer should be disabused before being able to put this into perspective. Chief among them is not to listen to those who tell you boxing is the sport of gentlemen. Don’t believe for one moment the codswallop they tell you about the “art” of boxing – this is not even a sport in the true sense of the word. A distinction between “boxing” and “fighting”? Not in my book. It exists solely for two men to try to knock each other out – if they can, they will.

Stopping the fight (“technical knockout” or TKO) is the next best option any contestant will aim for, but enduring the full 12 or 15 rounds in a punishing war of attrition, decided by points, is what boxers will avoid if at all possible – and the “points decision” often bears no basis to the reality of what you’ve seen.

In short, this is showbiz, not sport. After all, the points are not determined by any scientific method like punches landed, but the arcane and subjective view of often biased officials at ringside, which frequently bear little relation to the reality of the fight they have witnessed. So many occasions the neutrality of referees has been called into question and you wonder if they saw the same fight you saw.

It’s often said that a British fighter can’t win in the US because of biased referees, a fate suffered by Amir Khan recently – though in his case the blatant interference in the referee cards did at least mean he won the right to a rematch. Let’s face facts here – this is not only not a sport, it’s corrupt too.

Whatever improvements have been made to the welfare and health of boxers in recent years, the fact is that some have died as a result of the beating they have taken in a fight, some (Michael Watson, Gerald McLellan and doubtless many others) have suffered blood clots, have nearly died but have suffered permanent brain damage.

And many more have suffered permanent damage from the results of a career of taking punches. No matter how brave the contestants, brain damage is no respecter of courage or durability, and the effect of repeated blows to the head can and does affect every boxer to a greater or lesser degree.

Ah, I hear you say, but they do know the risks and choose to do it. Sure, they took the risk, but we would not allow animals to suffer in this way – why humans? Audiences and TV channels pay for the privilege, boxing generates cash – that’s why. They hate dull contests, they bay for blood and usually get it. Ban boxing and it would go underground, they say, back to its origins in bare knuckle contests as in the Cribb-Molineaux bloodbath from 1810? That argument does not make boxing right, it just glamourises – or worse still, normalises – the brutality.

But coming back to the Chisora brawl, I seem to recall that it’s not just press conferences suffering unseemly and unpleasant impromptu punch-ups (assuming this was impromptu and not staged, which, given the nature of the promoters would not surprise anyone in the slightest), I seem to recall Mike Tyson bit off part of Evander Holyfield‘s ear in the ring. There may well have been many other instances. TV loved it, but don’t let anyone convince you that this is sport. If anything lowers the dignity of the human spirit, boxing is it.

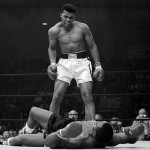

And if you’re in any doubt, see the sad state many ex-boxers get into. The great Muhammed Ali suffers from Parkinson’s disease, brought on, so say his medics, from being repeatedly punched about the head. It’s hypothetical whether he would still have got Parkinson’s disease had he not been a boxer, but there is a massively high incidence of neurological illnesses in boxers that is entirely preventable.

So here’s the thing: boxing is popular for one reason – it harks back to the murder and mayhem of contests going back to the Roman amphitheatre and beyond. If it’s not Lions v Christians, it has to be a contest with the semblance of order by virtue of the Queensbury rules, to convince us that this is regulated and safe. Baying for blood is a primeval human instinct, but the very antithesis of a true sporting spectacle, yet despite the protestations of nobility that is what spectators truly want.

People love the performance and the head-to-head hype and rivalry, knowing in the process that it degrades humanity. There’s a guilt factor at work here, something we should have long since moved on from, but feel compelled to retain. I’d say that if you want excitement, there are plenty of other options without seeing men (and now women) slug it out.

PS. This story becomes more farcical by the moment. Yes, Haye will fight Chisora in the UK under licences issued by the Luxembourg Boxing Federation, or whatever they call it. Lots of threats of legal action, lots more publicity, total farce!!

PPS. To see a sober analysis of the brutality of boxing, see Scorcese’s masterpiece, Raging Bull.

PPS. This article by Justin Cartwright from the London Evening Standard represents a view that warrants repetition in full. I certainly don’t agree with it but it goes some way to explaining the instincts that draw people to boxing: